Public debate over the safety of childhood vaccines, particularly the vaccine for measles, mumps and rubella, is typically linked with a 1998 research study – later discredited – that suggested that the MMR vaccine was associated with autism.9 Seth Mnookin’s book, The Panic Virus, suggests that media reporting of the study coupled with the 12 years it took until the study was retracted helped foster concerns about the safety of the MMR vaccine among, at least, some members of the public. And Dina Fine Maron suggests that the coincidental discovery of many neurological disorders around the age of 2 contributes to ongoing concerns about vaccines, especially among parents of young children.

A number of prominent public figures have expressed reservations about the safety of childhood vaccines, especially the MMR vaccine, which is recommended to be given to children between the ages of 12 and 15 months, followed by a second dose at the age of 4 to 6 years. For example, actor Robert De Niro selected a film for the Tribeca Film Festival that argued for a link between childhood vaccines and autism. The film was later dropped from the festival in response to protests, but De Niro, who has an autistic son, repeated his personal concerns about the safety of vaccines and urged people to see the film. A number of political figures have raised concerns about the safety of childhood vaccines. President Trump questioned the recommended schedule for childhood vaccines during a primary debate in 2015, met with members of the anti-vaccine movement during the 2016 campaign and as president-elect, reportedly asked Robert Kennedy Jr., the editor of a volume that argues the preservative used in some vaccines causes autism and other neurological disorders, to head a commission on vaccine safety.

A number of prominent public figures have expressed reservations about the safety of childhood vaccines, especially the MMR vaccine, which is recommended to be given to children between the ages of 12 and 15 months, followed by a second dose at the age of 4 to 6 years. For example, actor Robert De Niro selected a film for the Tribeca Film Festival that argued for a link between childhood vaccines and autism. The film was later dropped from the festival in response to protests, but De Niro, who has an autistic son, repeated his personal concerns about the safety of vaccines and urged people to see the film. A number of political figures have raised concerns about the safety of childhood vaccines. President Trump questioned the recommended schedule for childhood vaccines during a primary debate in 2015, met with members of the anti-vaccine movement during the 2016 campaign and as president-elect, reportedly asked Robert Kennedy Jr., the editor of a volume that argues the preservative used in some vaccines causes autism and other neurological disorders, to head a commission on vaccine safety.

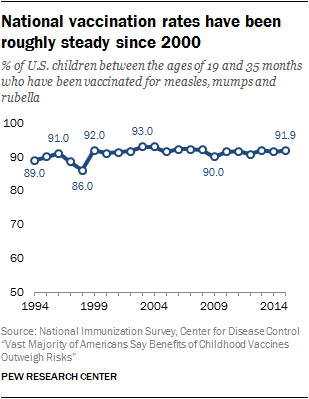

Roughly nine-in-ten children receive the first dose of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine by the age of 35 months. In 2014, 91.9 percent of children ages 19 to 35 months had received the MMR vaccine, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, local vaccination rates can vary widely. A preliminary analysis published in JAMA Pediatrics suggested that the “substandard” vaccination rates – that is, vaccine rates below the level needed to protect the population from the measles disease – were likely to blame for the outbreak of measles originating at Disneyland in December 2014 and continuing through the early months of 2015.

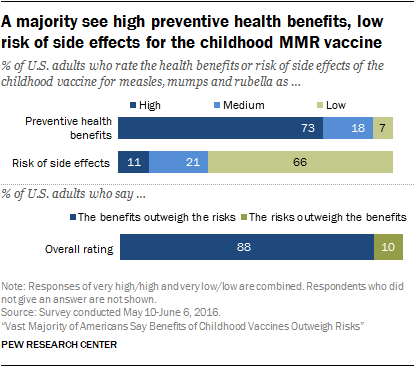

The new Pew Research Center survey finds that a large majority of Americans consider the preventive benefits of the MMR vaccine to be high and the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine to be low. Overall, some 88% of Americans think the benefits of the MMR vaccine outweigh the risks; just one-in-ten dissent from this view.

Pockets of Americans appear more hesitant about the safety of vaccines, however. Parents of younger children (from birth to age 4) tend to rate the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine as higher and the benefits lower than parents with older children and those with no minor-age children. Blacks are more likely than whites to think there is either a medium or high risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine. And people with less knowledge about science and those with lower levels of education and family income also express comparatively more concern about the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine. On the flip side, people with high knowledge about science, higher education and higher family income levels are comparatively more inclined to see high health benefits from the MMR vaccine.

In addition, people’s conventional and alternative medicine practices tend to align with their perceptions of the risks and benefits of the vaccine. The minority of Americans who report never using over-the-counter medications for cold and flu symptoms, for example, are especially likely to see medium or high risk from the MMR vaccine. Similarly, those who have used alternative medicine instead of conventional treatment are more inclined to think the risk of side effects from the vaccine is medium or high.

When it comes to policy views, a large majority of Americans support school-based requirements for the MMR vaccine in order to protect public health; fewer than two-in-ten think parents should be able to choose whether or not to have their children vaccinated for measles, mumps and rubella.

Older adults, especially those ages 65 and older, and those with high science knowledge are particularly strong in their support for school-based policy requirements to vaccinate children for measles, mumps and rubella. Reports that affluent communities have lower vaccination rates lead some to speculate that people with higher incomes are particularly concerned about the safety of the MMR vaccine. The survey finds, however, that people with higher family incomes see low risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine and are especially strong in their support for a requirement that all children be vaccinated against MMR in order to attend public schools.

White evangelical Protestants are slightly more likely than either white mainline Protestants or Catholics to think that parents should able to decide not to have their children vaccinated, even if that may create health risks for other children and adults. And, political conservatives, regardless of party affiliation, are more likely than either moderates or liberals to support parents being able to choose whether to have their children vaccinated. Majorities of white evangelical Protestants and political conservatives, however, support a school-based requirement for the MMR vaccine.

Smaller majorities of people who say they never take over-the-counter medications for cold and flu symptoms and those who have used alternative medicine instead of conventional treatment support school-based requirements for the MMR vaccine; comparatively more in these groups say that parents should be able to decide whether their children should be vaccinated for MMR even if that decision creates health risks for others.

Personal concern about childhood vaccine issues

Some 42% of Americans say that they care “a great deal” about issues related to childhood vaccines. An additional 39% say they care “some,” while a small share, 17%, say they care not too much or not at all about these issues.

Some 42% of Americans say that they care “a great deal” about issues related to childhood vaccines. An additional 39% say they care “some,” while a small share, 17%, say they care not too much or not at all about these issues.

Women are more likely than men to be deeply concerned about childhood vaccine issues (48% of women vs. 36% of men care a great deal about these issues). A larger share of blacks (61%) than either Hispanics (43%) or whites (37%) report caring a great deal about childhood vaccine issues.

About half (49%) of parents with young children (up to age 4) care deeply about childhood vaccine issues, as do 40% of those who do not have minor-age children.

There are no differences in level of concern between mothers and fathers of minor-age children or across education or income levels.

There are no more than modest differences in beliefs about the benefits and risks of the MMR vaccine by levels of concern about childhood vaccine issues.

A large majority of Americans see benefits from childhood vaccines, but several subgroups show comparatively more concern about vaccine risks

Most Americans rate the preventive health benefits of childhood vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella as high and the risk of side effects as low. Fully 73% of U.S. adults say the health benefits of the MMR vaccine are high, while a quarter of adults say the benefits are medium (18%) or low (7%). On the flip side, most Americans consider the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine to be low (66%), 21% say the risks are medium and 11% say the risks are high.10

Most Americans rate the preventive health benefits of childhood vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella as high and the risk of side effects as low. Fully 73% of U.S. adults say the health benefits of the MMR vaccine are high, while a quarter of adults say the benefits are medium (18%) or low (7%). On the flip side, most Americans consider the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine to be low (66%), 21% say the risks are medium and 11% say the risks are high.10

When asked to weigh the risks and benefits of childhood vaccines together, an overwhelming majority of Americans say the benefits of childhood vaccines outweigh the risks (88%), and only one-in-ten say the risks outweigh the benefits.

Those high in science knowledge are especially likely to see health benefits from the MMR vaccine; fewer parents of young children, young adults and blacks perceive high benefits

While most Americans are in agreement that childhood vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella have high preventive health benefits and a low risk of side effects, there are notable differences in views among subgroups. People with more science knowledge (as well as those with higher levels of education) are especially inclined to see benefits from the MMR vaccine.11

While most Americans are in agreement that childhood vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella have high preventive health benefits and a low risk of side effects, there are notable differences in views among subgroups. People with more science knowledge (as well as those with higher levels of education) are especially inclined to see benefits from the MMR vaccine.11

Parents of young children along with blacks are less inclined to see benefits and comparatively more inclined to say the risk of side effects of the MMR vaccine is medium or high.

For example, fully 91% of those with high science knowledge rate the preventive health benefits as high, compared with 55% of those with low science knowledge. By the same token, 19% of those with high science knowledge rate the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine as medium or high, compared with 47% of those with low science knowledge. A similar pattern occurs by education; people with a postgraduate degree are more inclined than those with a high school diploma or less to see the health benefits of the MMR vaccine as high and the risks of side effects as at least medium.

People with lower family incomes are more inclined than people whose family income is at least $50,000 per year to see risks from the MMR vaccine and less inclined to see preventive health benefits.

Some 79% of whites say that preventive health benefits of childhood vaccines for MMR are high, compared with 56% of blacks and 61% of Hispanics.12 Blacks (44%) are also more likely than either whites (30%) or Hispanics (33%) to say the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine is medium or high.

Some 79% of whites say that preventive health benefits of childhood vaccines for MMR are high, compared with 56% of blacks and 61% of Hispanics.12 Blacks (44%) are also more likely than either whites (30%) or Hispanics (33%) to say the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine is medium or high.

Parents of children ages 0 to 4, a group that tends to skew younger than the population as a whole, are less inclined than other adults to believe that the preventive health benefits of childhood vaccines are high (60% vs. 75% of those with only older children and 76% of those without minor-age children). Parents with children under age 4 are relatively more likely to say the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine is medium or high (43% vs. 29% of those with no minor-age children).

There are no more than modest differences between men and women in perceptions of benefit and risk from the MMR vaccine.

Majorities of all major religious groups rate the preventive health benefits as high, and minorities rate the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine as high or medium. Black Protestants, like blacks in general, are less likely to consider the preventive benefits of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine to be high and more inclined to see the risk of side effects from such a vaccine as medium or high. Other religious groups tend to give similar assessments of the benefits and risks from the MMR vaccine.

Majorities of all major religious groups rate the preventive health benefits as high, and minorities rate the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine as high or medium. Black Protestants, like blacks in general, are less likely to consider the preventive benefits of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine to be high and more inclined to see the risk of side effects from such a vaccine as medium or high. Other religious groups tend to give similar assessments of the benefits and risks from the MMR vaccine.

When people give their overall judgment of the trade-offs, fully 88% of Americans say the benefits of childhood vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella outweigh the risks, just one-in-ten (10%) say otherwise.

There are modest differences by science knowledge, parent status, age, race and ethnicity. People with high (93%) or medium (90%) science knowledge are more likely than those with low science knowledge (81%) to think the benefits of the MMR vaccine outweigh the risks. Whites (92%) are more inclined than blacks (82%) and Hispanics (78%) to say the benefits of childhood vaccines outweigh the risks.

Some 81% of parents with children ages 0 to 4 say the preventive health benefits of the MMR vaccine outweigh the risks, compared with 90% of those with no children under age 18. Similarly, younger adults, ages 18-29, are somewhat less likely than older age groups to consider the benefits of vaccines to outweigh the risks (79% compared with at least 90% of those in older age groups.)

Statistical models underscore the strong relationship between people’s level of science knowledge, their age and their parent status in predicting their beliefs about the MMR vaccine. There are also modest race differences when it comes to views on the preventive health benefits of the MMR vaccine even after controlling for other factors. For details, see Appendix A.

People’s medical care practices are also linked to their beliefs about the MMR vaccine

People’s practices regarding conventional and alternative medicine are also associated with their views about childhood vaccines. In particular, those who never take over-the counter medication and people who have used alternative medicine instead of conventional medical treatment perceive higher risks from the MMR vaccine, compared with other Americans.

People’s practices regarding conventional and alternative medicine are also associated with their views about childhood vaccines. In particular, those who never take over-the counter medication and people who have used alternative medicine instead of conventional medical treatment perceive higher risks from the MMR vaccine, compared with other Americans.

Some 49% of people who say they never take over-the-counter medications consider the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine to be medium or high. By comparison, 33% of those who take over-the counter medications for cold and flu symptoms right away say the same. Those who never take over-the-counter medications are also less likely to rate the preventive health benefits of the MMR vaccine as high (59% do so vs. 73% among those who take over-the-counter medications right away).

Similarly, people who have used alternative medicine instead of traditional, Western-based medical treatment are somewhat more likely to see a higher risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine. Some 42% of this group says the risks of the MMR vaccine are medium or high, compared with three-in-ten (30%) among those who have never used alternative medicine. Ratings of benefits from the MMR vaccine are roughly the same across these groups.

When Americans weigh the benefits and risks of childhood vaccines, similar patterns emerge. While an overwhelming majority of all subgroups say the benefits of the MMR vaccine outweigh the risks, people who never take over-the-counter medications are slightly more inclined to think the risks outweigh the benefits. Some 74% of those who report never taking over-the-counter medications say the benefits outweigh the risks, 23% of this group says the risks predominate. In contrast, nearly all of those who take over-the-counter medications for cold or flu symptoms right away say the benefits of the MMR vaccine outweigh the risks (91% vs. 7%).

When Americans weigh the benefits and risks of childhood vaccines, similar patterns emerge. While an overwhelming majority of all subgroups say the benefits of the MMR vaccine outweigh the risks, people who never take over-the-counter medications are slightly more inclined to think the risks outweigh the benefits. Some 74% of those who report never taking over-the-counter medications say the benefits outweigh the risks, 23% of this group says the risks predominate. In contrast, nearly all of those who take over-the-counter medications for cold or flu symptoms right away say the benefits of the MMR vaccine outweigh the risks (91% vs. 7%).

Summary judgments of the risk-benefit trade-offs are about the same regardless of experience with alternative medicine.

Statistical models find people’s practices regarding over-the-counter medications and alternative medicine are significantly associated with perceived risk from childhood vaccines when controlling for demographic and other factors. For details, see Appendix A.

Perceived safety of childhood vaccines in 2015 survey linked with age, education

A Pew Research Center survey conducted in 2015 shortly after an outbreak of measles, found a large majority (83%) of Americans thought childhood vaccines, such as MMR, were generally safe for healthy children, while only 9% believed childhood vaccines were not safe. Older adults and those with more education were a bit more likely to consider vaccines safe. Fully 91% of those ages 65 and older said vaccines were safe for healthy children; by comparison, 77% of those ages 18 to 29 said vaccines were safe. Roughly nine-in-ten (92%) college graduates said childhood vaccines were safe for healthy children. Smaller majorities of those with some college (85%) or a high school diploma or less (77%) said vaccines were generally safe.

More than eight-in-ten Americans favor school-based vaccine requirements; a minority says vaccines should be parents’ choice

A majority of the American public (82%) says the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine should be a requirement “in order to attend public schools because of the potential risk for others when children are not vaccinated.” Some 17% of Americans believe that “parents should be able to decide not to vaccinate their children, even if that may create health risks for other children and adults.”

A majority of the American public (82%) says the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine should be a requirement “in order to attend public schools because of the potential risk for others when children are not vaccinated.” Some 17% of Americans believe that “parents should be able to decide not to vaccinate their children, even if that may create health risks for other children and adults.”

Majorities of Americans across a range of demographic and educational groups support school requirements for the MMR vaccine. Older adults are especially strong in their support. Fully nine-in-ten (90%) adults ages 65 and older favor a school-based requirement that children be vaccinated for measles, mumps and rubella. A smaller majority of younger age groups say the same (77% of adults ages 18-29 and 78% of adults ages 30-49).

Parents of younger children, school-age children and those with no minor-age children hold roughly similar views on this issue with a majority of all three groups saying that healthy schoolchildren should be required to be vaccinated because of the health risk to others when children are not vaccinated.

People who care a great deal about childhood vaccine issues are more inclined to support school-based MMR vaccine requirements (87% favor this, compared with 80% of those who care some about childhood vaccine issues and 78% of those who care not too much or not at all about childhood vaccine issues).

On average, people with higher family incomes, earning at least $100,000 annually, are a bit more inclined than those with lower incomes to support requiring the MMR vaccine for all public schoolchildren.

Views about this issue are about the same by political party. However, political conservatives are more likely than either moderates or liberals to say that parents should be able to decide not to have their children vaccinated, even if that decision creates health risks for others.

White evangelical Protestants (22%) and the religiously unaffiliated (21%) are slightly more likely than white mainline Protestants and Catholics to say parents should be able to decide not to have their children vaccinated, even if that may create health risks for other children and adults. However, as noted above, the major religious groups have roughly similar views of the risks and benefits from the MMR vaccine.

The survey found no or only small differences by gender, race and education on this issue.

Statistical models show that, on average, adults ages 65 and older are more likely than younger age groups to support school-based MMR vaccine requirements when controlling for demographic and other factors. In addition, conservatives are more likely than either moderates or liberals to say that parents should be able to decide whether to have their children vaccinated. Evangelical Protestants (of any race) are more likely than mainline Protestants to say that parents should be able to decide whether to have their children vaccinated even if it creates a health risk for others, when statistically controlling for other factors. For details, see Appendix A.

Public views on requiring vaccines in 2014 survey also differed by age, religion

A 2014 Pew Research Center survey asked a more general question about vaccines. In that survey, 68% of U.S. adults said children should be required to be vaccinated for childhood diseases such as measles, mumps, rubella and polio, while 30% said parents should be able to decide whether to have their children vaccinated. Adults younger than 30 were less inclined than those ages 65 and older to think such vaccines should be required (59% of those ages 18 to 29, compared with 79% of those ages 65 and older). White evangelical Protestants were comparatively less inclined to favor requiring childhood vaccines (59%). By comparison, 70% of white mainline Protestants and 76% of Catholics supported requiring childhood vaccines. Views on this issue were slightly different by party; 64% of Republicans and leaning Republicans said vaccines should be required, compared with 74% of Democrats and leaning Democrats.

People’s practices in using conventional and alternative medicine are linked with their beliefs about school requirements for the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine

People who never take over-the-counter medication for cold or flu symptoms and people who have used alternative medicine instead of conventional treatment are more likely than other Americans to say parents should be able to decide whether to have their children vaccinated, even if not vaccinating them may create health risks for other people.

People who never take over-the-counter medication for cold or flu symptoms and people who have used alternative medicine instead of conventional treatment are more likely than other Americans to say parents should be able to decide whether to have their children vaccinated, even if not vaccinating them may create health risks for other people.

A third (33%) of people who never take over-the-counter medications say that parents should be able to decide whether to have their children vaccinated; two-thirds (66%) of this group say that children should be required to be vaccinated in order to attend public school. In contrast, just 12% of those who take over-the-counter medications right away say that parents should be able to decide whether to have their children vaccinated for measles, mumps and rubella; 86% say children should be required to be vaccinated in order to attend school.

Similarly, people who have used alternative medicine instead of traditional medicine are a bit more inclined (26% compared with 13% of those who have never tried alternative medicine) to think parents should be able to decide whether to have their children vaccinated, though the majority support a school-based requirement for the MMR vaccine.

Statistical models find that people’s practices regarding over-the-counter medications and alternative medicine are significantly associated with support for school-based MMR vaccine requirements. On average, those who never take over-the-counter medications for cold or flu symptoms and those who have used alternative medicine instead of conventional medicine are more likely to say that parents should be able to decide whether to have their children vaccinated, when controlling for demographic and other factors. For details, see Appendix A.