The share of the global population that is poor plunged from 29% in 2001 to 15% in 2011, elevating the living standards of 669 million people, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of the most recently available data. The magnitude of this decline seems to be without precedent in the past two centuries.

In the Pew Research study, anyone living on $2 or less daily is considered poor. (Figures are expressed in 2011 prices and purchasing power parities.)

But what exactly does it mean to live on $2 per day? And how does that compare with the notion of poverty in richer countries?

But what exactly does it mean to live on $2 per day? And how does that compare with the notion of poverty in richer countries?

Deciding where the poverty line falls is tricky. There are likely as many unresolved questions as there are answers, whether in emerging nations or in advanced economies like the United States.

The examples of India, where one-in-five people live on $2 or less daily, and the U.S., where one-in-50 do, give or take, are instructive.

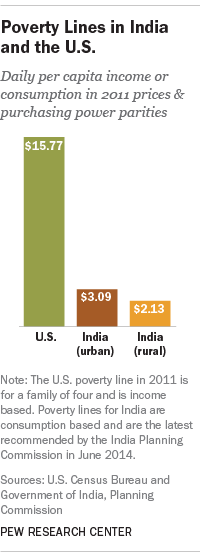

The $2 line arrived at in our analysis is close to the current poverty line established by India. This may be bumped up to $2.46 if a recent recommendation from the India Planning Commission is adopted. The recommended poverty line ranges from $2.13 in rural India – where nearly 70% of the population lives – to $3.09 in urban India.

The poverty line proposed for India uses minimum daily calorie requirements as a starting point. Setting the daily requirements at 2,155 calories per person in rural areas and 2,090 calories in urban areas, and taking into account protein and fat requirements, the Planning Commission established the requisite food budgets using survey data on the consumption patterns of Indian families in 2011. Poverty-line expenditures on non-food items, such as shelter, clothing and medical needs, were also established by taking survey data into account.

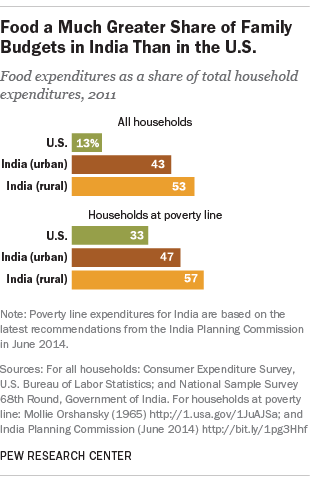

How much do you need to spend on food to consume the baseline calories in India? The answer, according to survey data, is $1.22 per day in rural India and $1.44 per day in urban India. Note that, at the poverty line, food consumption alone would take up 57% of a rural family’s budget and 47% of an urban family’s budget. Overall, the average Indian family is estimated to spend 53% of its budget on food in rural areas and 43% in urban areas.

The standards proposed for India contrast sharply with those in the U.S. The daily cost of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s thrifty food plan in July 2011 was $5.07 per person for a family of four, with two children ages 6-8 and 9-11 years. This budget allows for meals at home that consist of grains, vegetables, fruits, milk products, meat, beans and other foods, and that meet the U.S. government’s nutrition standards.

Not unlike India, the poverty line in the U.S. is also built up from the USDA’s baseline food plan. As proposed by Mollie Orshansky in 1965, the U.S. poverty line is defined as an income of three times the cost of the thrifty food plan (meaning food would take up 33% of a family’s income at the poverty line). By that standard, the U.S. poverty line in 2011 was $15.77 per day per capita for a household of four (the precise line varies by household size and composition).

Not unlike India, the poverty line in the U.S. is also built up from the USDA’s baseline food plan. As proposed by Mollie Orshansky in 1965, the U.S. poverty line is defined as an income of three times the cost of the thrifty food plan (meaning food would take up 33% of a family’s income at the poverty line). By that standard, the U.S. poverty line in 2011 was $15.77 per day per capita for a household of four (the precise line varies by household size and composition).

Compared with the food budget for an urban Indian family at the poverty line, the food budget in the U.S. is 3.5 times higher – $5.07 vs. India’s $1.44. The overall U.S. poverty-line budget is five times greater than India’s, $15.77 vs. $3.09.

Why this disparity? Orshansky wrote:

“In many parts of the world, the overriding concern for a majority of the populace every day is still ‘Can I live?’ For the United States as a society, it is no longer whether but how. Although by the levels of living prevailing elsewhere, some of the poor in this country might be well-to-do, no one here today would settle for mere subsistence as the just due for himself or his neighbor, and even the poorest may claim more than bread.”

In other words, poverty is often about relative deprivation. Setting an absolute standard, such as $2 per day per person, and counting how many people better the standard, is a key to measuring progress. But progress in and of itself may beget its own expectations.