The Supreme Court will hear two cases this term about whether police can search the contents of a mobile device without a warrant.

The legal boundaries of technology and privacy have become more urgent to address as mobile connectivity has become central to Americans’ lives. According to the Pew Research Center 58% of adults own smartphones and 42% own tablet computers. Half of American cell phone owners have downloaded apps to their mobile devices.

Apps are pieces of software that allow users to interact with mobile services, from online banking, to news and games and driving directions. When they download apps, many users may not realize the apps collect information about them. The cases before the high court could clarify whether police searches of smartphones, including app content, without a warrant represent “unreasonable search and seizure” and violate citizens’ privacy in a new technological era.

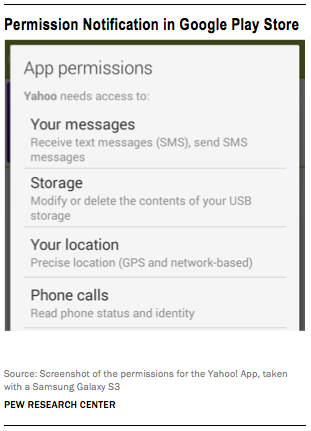

Apps are central to these cases because when a smartphone user downloads an app, the owner is usually prompted by the app to gain permission to access other information from the phone. For example, in the Android operating system, users are first presented with what information and features an app requires when they attempt to download an app. This information is organized into a list of “permissions.” Users must either accept the entire list, or decline to use the app.

Apps are central to these cases because when a smartphone user downloads an app, the owner is usually prompted by the app to gain permission to access other information from the phone. For example, in the Android operating system, users are first presented with what information and features an app requires when they attempt to download an app. This information is organized into a list of “permissions.” Users must either accept the entire list, or decline to use the app.

According to a survey of 1,300 apps conducted in early 2013, apps can vary widely in how many permissions they require with one app asking for 47 permissions, and others only one. In all, there were 126 different permissions apps asked for, according to 2013 data – but the list of possible permissions continues to grow. Users are presented with those permissions grouped in to broad categories. Like the overall list of permissions the categories users are presented with also continues to change, among the current most common categories to note (this list is not exhaustive):

- Your Location This is a category of permissions which includes several methods an app could use to find a user’s location. For example, “Precise Location” lets an app find a user’s location using the GPS of the device as well as cell phone towers and Wi-Fi networks.

- Your Personal Information This category covers a broad range of permissions that allow apps to access information like a user’s browser history and bookmarks, calendar events and contact data.

- Services That Cost You Money This permissions categorycovers functions of the device that could affect the user’s cell phone bill, such as allowing apps to send text messages or make phone calls. This category signals to the user that the third party app now has access to core functions of the device that could interact with the cell provider (such as Verizon or AT&T).

- Your Accounts– Some permission categories are narrow in scope, but this category broadly covers dozens of permissions that give apps access to various user accounts including accounts like Gmail or Google Maps.

- Hardware– These permissions not only cover information stored on the phone, but also allow the app to interact with the device itself. For example, the “Take Pictures or Video” permission allows an app access to the device’s camera.

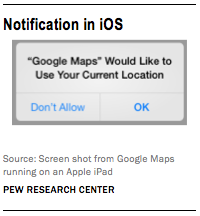

On Apple devices, users are informed of the same information, but in a different way. On iOS devices, users are not presented with a specific list of permissions when they install an app; instead, they install the app and then the app informs them when it needs access to certain information or features.

On Apple devices, users are informed of the same information, but in a different way. On iOS devices, users are not presented with a specific list of permissions when they install an app; instead, they install the app and then the app informs them when it needs access to certain information or features.

This method is sometimes referred to as “just-in-time” notification. In this case, if an app requires a user’s location information, the user is asked if they would allow the app to do that when the app first needs to. This is different from the Android, where the user is told on initial install that an app may need location information at some point.