Jobs in which social, fundamental, analytical or managerial skills are more important pay better than jobs requiring higher levels of mechanical skills. Wages in these jobs have also increased at a higher rate than in other jobs since 1980, as has the pace of hiring. Workers have raised their education level in response: The share of American workers with a four-year college degree increased steadily from 1980 to 2018, especially among women.16 But while women’s earnings increased faster than men’s earnings over the period, a substantial gender wage gap remains.

Jobs in which social, fundamental, analytical or managerial skills are more important pay better than jobs requiring higher levels of mechanical skills. Wages in these jobs have also increased at a higher rate than in other jobs since 1980, as has the pace of hiring. Workers have raised their education level in response: The share of American workers with a four-year college degree increased steadily from 1980 to 2018, especially among women.16 But while women’s earnings increased faster than men’s earnings over the period, a substantial gender wage gap remains.

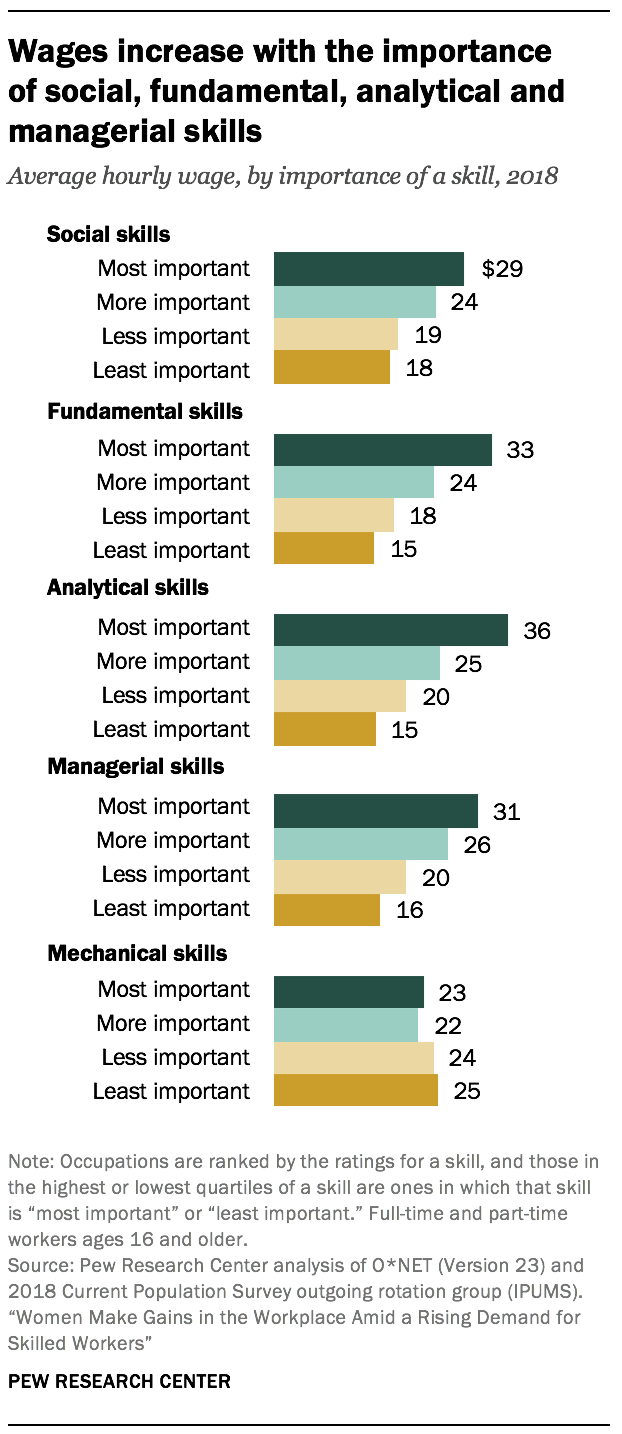

In 2018, wages in occupations in which nonmechanical skills are most important were about twice as high as wages in occupations in which these skills are least important. For example, jobs with the greatest need for fundamental skills paid an average hourly wage of $33, compared with $15 in jobs with the least need for fundamental skills. (Wages are expressed in 2018 dollars.)

A somewhat greater rise in wages is seen when occupations are ranked by analytical skills, with the average wage rising from $15 in the least analytically skilled jobs to $36 in the most analytically skilled jobs. Moving from jobs in which social skills are least important to jobs in which they are most important boosts wages from $18 to $29, on average.

It is important to note that the observed increase in earnings with the importance of a skill is not necessarily the result of the rising importance of only that skill. As noted, social, fundamental, analytical and managerial skills tend to rise and fall in importance in concert. Thus, if wages are seen to rise with the importance of analytical skills, part of the reason is that the importance of social, fundamental and managerial skills has also increased to some extent. Determining the precise contribution of a single skill to raising wages is a difficult proposition.

Unlike with nonmechanical skills, wages barely change with the importance of mechanical skills. Occupations in which mechanical skills are most important paid an average hourly wage of $23 in 2018, compared with $25 in occupations in which mechanical skills are least important.

Unlike with nonmechanical skills, wages barely change with the importance of mechanical skills. Occupations in which mechanical skills are most important paid an average hourly wage of $23 in 2018, compared with $25 in occupations in which mechanical skills are least important.

The reason why wages do not increase with the need for mechanical skills is that the demand for nonmechanical skills moves in opposition to the demand for mechanical skills. In other words, jobs most in need of mechanical skills often are less in need of other skills, blunting the potential for wages to rise with the importance of mechanical skills. Conversely, as the need for mechanical skills wanes, the need for other skills grows stronger, serving to buffer wages.

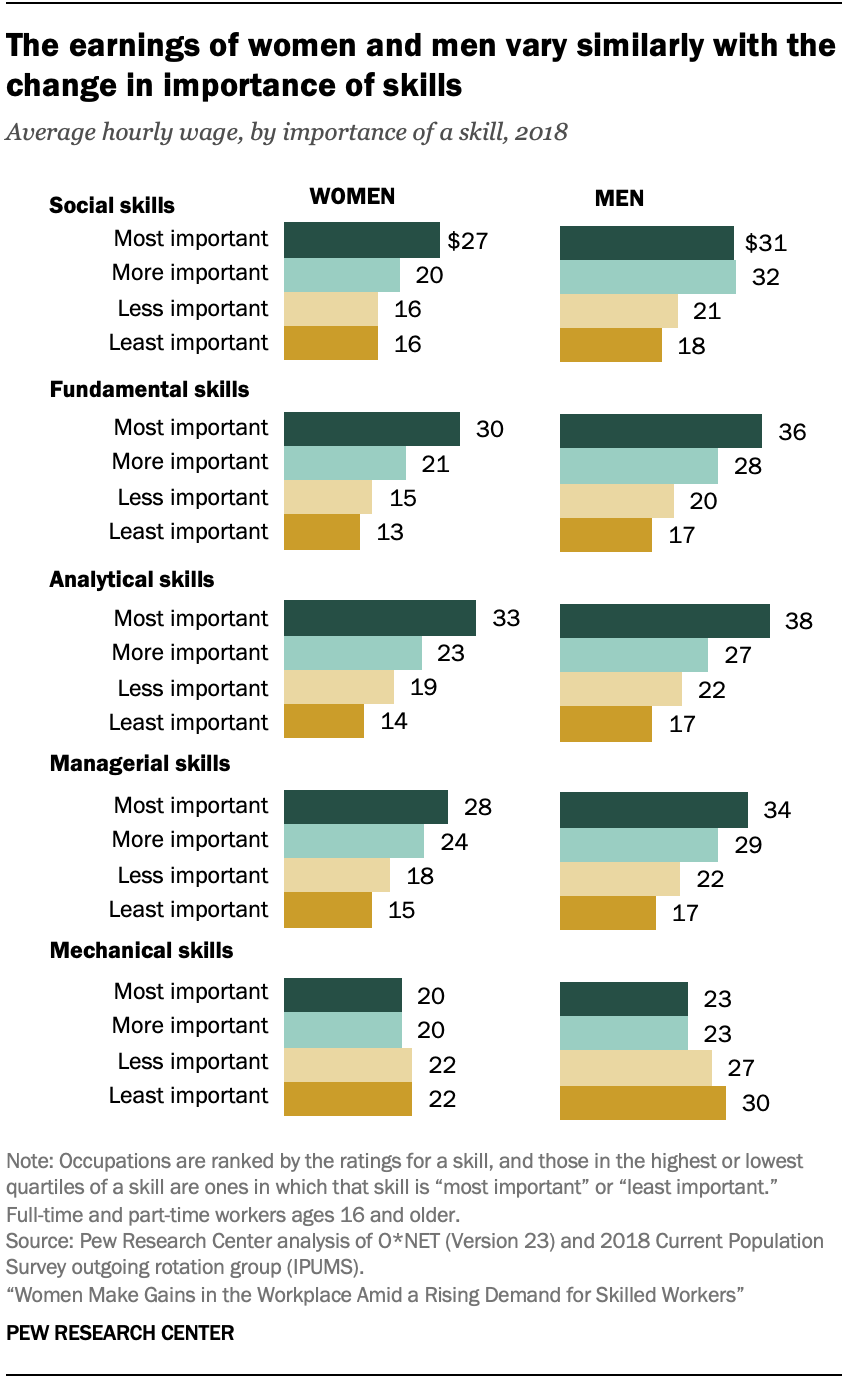

The earnings of women and men vary similarly across the different types of skills and their importance. For both women and men, the highest paying jobs in 2018 were those in the topmost ranking of analytical skills, $33 per hour for women and $38 per hour for men. And both women and men would more than double their earnings moving from low-analytical-skill jobs to high-analytical-skill jobs. A similar pattern prevails across occupations grouped by importance of social, fundamental and managerial skills.

Neither women nor men experience an increase in earnings with a rise in the importance of mechanical skills.

The evidence on women’s and men’s wages underscores the ubiquity of the gender wage gap. Regardless of the classification of occupations – by skill type or the importance of a skill – women’s earnings fell short of men’s earnings in 2018. For example, women in occupations with the greatest need for fundamental skills earned $30 per hour, 83% as much as what men earned per hour in similar jobs ($36). A gap of similar magnitude is observed in most groupings of jobs by skill type and importance, an issue taken up in more detail later in this chapter.

Women’s earnings are rising faster than men’s, especially in high-skill jobs

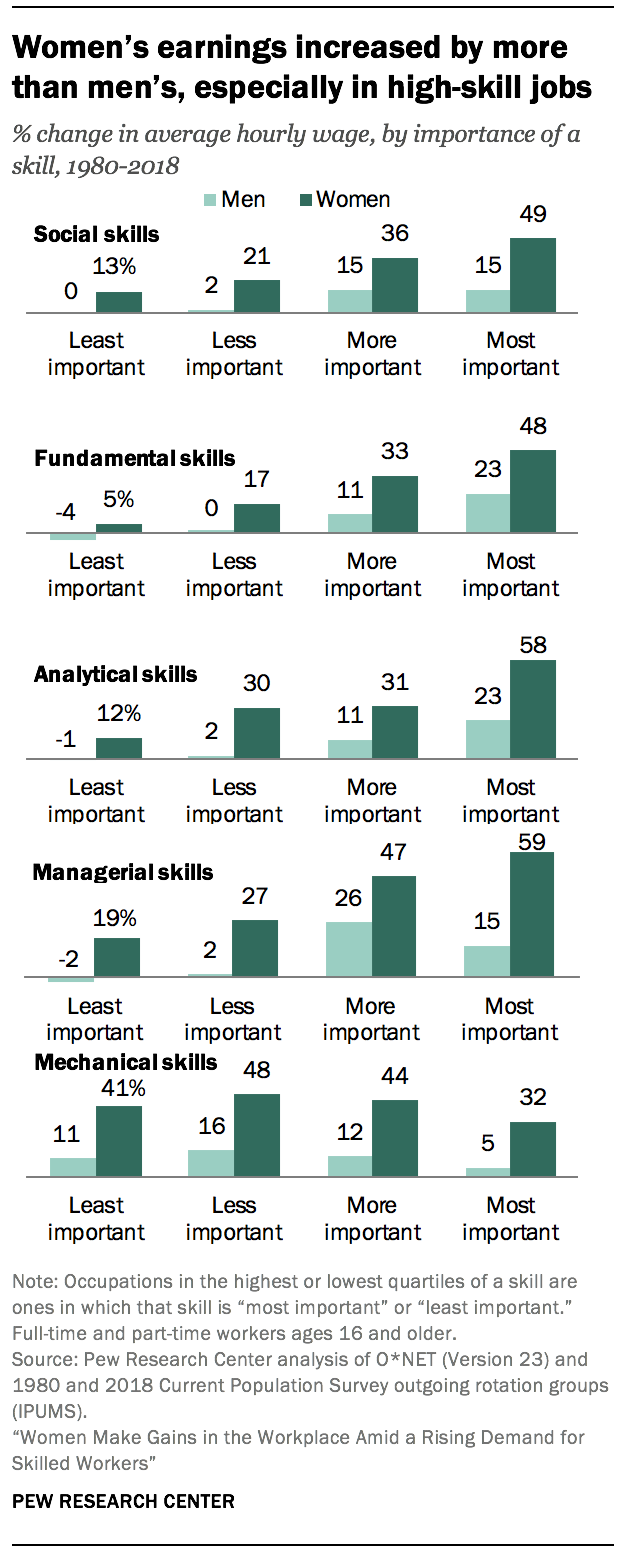

The growing demand for workers more proficient in social, fundamental, managerial and analytical skills has translated into more rapidly growing wages in high-skill jobs. In other words, the returns on nonmechanical skills, as measured by the gain in wages with the increase in importance of a skill, rose from 1980 to 2018. This was true for both women and men.

Overall, the average hourly wage at the workplace increased 24% from 1980 to 2018, from $19 to $24.17 Women’s earnings rose at a greater rate over the period, by 45%, from $15 in 1980 to $22 in 2018. In contrast, men’s wages increased 14%, from $23 to $26.

Overall, the average hourly wage at the workplace increased 24% from 1980 to 2018, from $19 to $24.17 Women’s earnings rose at a greater rate over the period, by 45%, from $15 in 1980 to $22 in 2018. In contrast, men’s wages increased 14%, from $23 to $26.

Amid relatively lackluster wage growth for men overall, men’s earnings increased by more than 20% in jobs in which fundamental and analytical skills are most important or in which managerial skills are more (but not most) important. At the same time, men’s wages were about unchanged in jobs in which nonmechanical skills are either less or least important. Thus, only men working in higher—nonmechanical-skill jobs experienced notable wage growth from 1980 to 2018.

Women experienced more rapid wage growth than men across the board. Their average hourly wage increased by nearly 50% in jobs in which social and fundamental skills are most important and by close to 60% in jobs in which analytical and managerial skills are most important. In the second tier of skills – jobs in which these skills are more important – women’s earnings increased by 47% in the realm of managerial skills and by upwards of 30% in the realms of social, fundamental and analytical skills. As with men, the growth in wages for women was much higher at the top of the skills ladder than at the bottom.

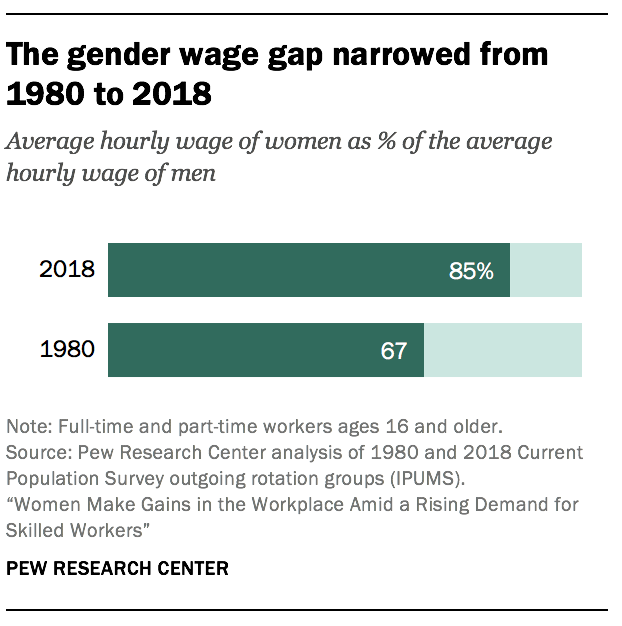

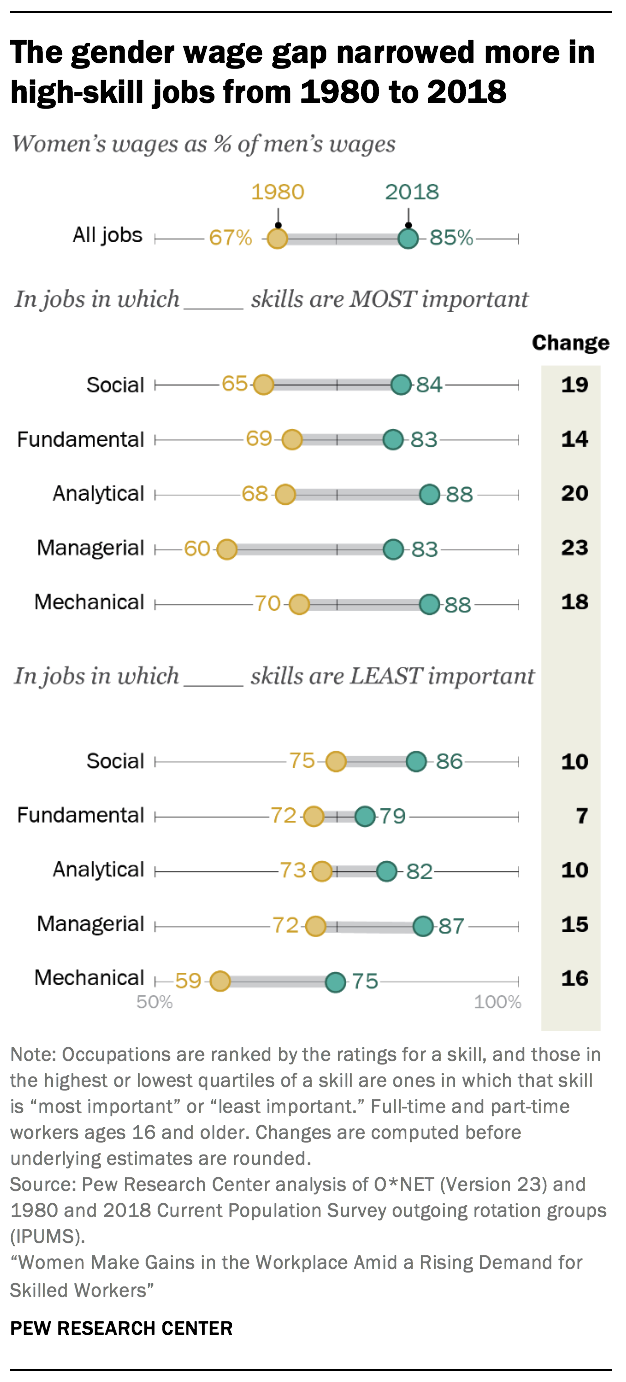

The gender wage gap narrowed from 1980 to 2018, more so in high-skill jobs

The more rapid increase in women’s earnings from 1980 to 2018 resulted in a narrowing of the gender wage gap. In 1980, the average hourly wage of women was 67% of the average hourly wage of men, $15 vs. $23. By 2018, women earned 85% as much as men, $22 vs. $26, on average.

The more rapid increase in women’s earnings from 1980 to 2018 resulted in a narrowing of the gender wage gap. In 1980, the average hourly wage of women was 67% of the average hourly wage of men, $15 vs. $23. By 2018, women earned 85% as much as men, $22 vs. $26, on average.

Put another way, the gender wage gap narrowed from 33 cents to the dollar in 1980 to 15 cents to the dollar in 2018.

The gender wage gap in 1980 tended to be wider in high-skill occupations. For example, in occupations placing the highest importance on managerial skills, women earned only 60% as much as men on average. On the other hand, in occupations placing the least importance on managerial skills, women earned 72% as much as men. This pattern also prevailed with respect to social, fundamental and analytical skills in 1980.

Despite the initial lag in high-skill occupations, women succeeded in closing the gender wage gap by more in those occupations. For instance, in occupations placing the most importance on social skills, women’s earnings increased from 65% of the level of men’s earnings in 1980 to 84% of the level in 2018. This gain of 19 cents to the dollar was nearly twice the gain women made in low-social-skill jobs. In those jobs, the wage gap narrowed by 11 cents, from women earning 75% as much as men to 86% as much.18

The greatest wage closure achieved by women was in high-managerial-skill jobs. From earning 60% as much as men in these jobs in 1980, women progressed to earning 83% as much as men in 2018, a narrowing of 23 percentage points. The closure of the wage gap in high-analytical-skill jobs was almost as notable, with women advancing from earning 68% to 88% as much as men. By 2018, then, the gender wage gap was about the same across both high- and low-skill jobs when grouped by the importance of social, fundamental, analytical or managerial skills.

The greatest wage closure achieved by women was in high-managerial-skill jobs. From earning 60% as much as men in these jobs in 1980, women progressed to earning 83% as much as men in 2018, a narrowing of 23 percentage points. The closure of the wage gap in high-analytical-skill jobs was almost as notable, with women advancing from earning 68% to 88% as much as men. By 2018, then, the gender wage gap was about the same across both high- and low-skill jobs when grouped by the importance of social, fundamental, analytical or managerial skills.

A rising level of education among women is one reason why the gender wage gap closed from 1980 to 2018. In 1980, 16% of employed women ages 16 and older had completed four years of college education or more, compared with 20% of men. By 2018, 40% of women had completed at least a four-year college program, compared with 35% of men. Thus, whereas women once lagged men in college completion by 4 percentage points, they are now ahead of men by 5 points overall and are better equipped for higher-skill jobs.

Not coincidentally, the turnabout in education was among the sharpest within jobs in which managerial and analytical skills are most important. In 1980, only 19% of women in high-managerial-skill jobs had completed at least four years of college, compared with 42% of men in those jobs. By 2018, there was no discernable difference – 55% of women and 56% of men in high-managerial-skill jobs held a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education.

Over the same period, women in high-analytical-skill jobs went from lagging men in college completion in 1980, by 36% to 48%, to taking the lead by 2018, at 74% to 68%. The more pronounced transformation in education within high-skill jobs, compared with a muted shift within low-skill jobs, helps explain why the gender wage gap narrowed more in high-skill jobs than in low-skill jobs.

Over the same period, women in high-analytical-skill jobs went from lagging men in college completion in 1980, by 36% to 48%, to taking the lead by 2018, at 74% to 68%. The more pronounced transformation in education within high-skill jobs, compared with a muted shift within low-skill jobs, helps explain why the gender wage gap narrowed more in high-skill jobs than in low-skill jobs.

The narrowing of the gender wage gap also received an assist from a narrowing of the differences in the occupations and industries in which women and men work. As noted in the previous chapter, women made significant strides in moving out of lower-paying occupations and into higher-paying occupations from 1980 to 2018. An example of a lower-paying occupation women exited from is food preparation and serving, in which they earned $11 per hour in 2018, on average. An example of a higher-paying occupation women stepped into is financial specialists, in which they earned $31 per hour in 2018.

Higher levels of educational attainment among women and the shifts they made across occupations are intertwined with their rising profile in high-skill jobs. They are among the reasons why women are now in the majority in high social and fundamental skill jobs, are no longer underrepresented in high managerial skill jobs, and have greatly raised their share in high-analytical-skill jobs. To the extent that earnings increase with the importance of skills, independent of their relationship with schooling and occupation, these trends also helped to narrow the gender wage gap from 1980 to 2018.

A decline in the union membership rate from 1980 to 2018 also contributed to the observed decline in the gender wage gap. Specifically, in a change more detrimental to men’s wages, the union membership rate among men fell from 28% in 1983 to 12% in 2018, compared with a decrease from 18% to 11% among women.19

Job skills and higher levels of education are pulling women’s earnings closer to men’s, but other factors are driving a wedge

The persistence of a gap in the earnings of women and men is not entirely understood by scholars. Some of the factors that determine the earnings of workers are quantifiable, such as job skills, education level, work experience, union membership, hours worked, industry and occupation. But data on other factors, such as occupation-specific skills or the work environment, is often lacking. In addition, some factors that may result in a wage gap between women and men are difficult to measure. These include the responsibilities of motherhood and family and the effect they have on women’s engagement with the workplace when compared with men; gender stereotypes and discrimination; and differences in professional networking and in the inclination to negotiate for raises and promotions.

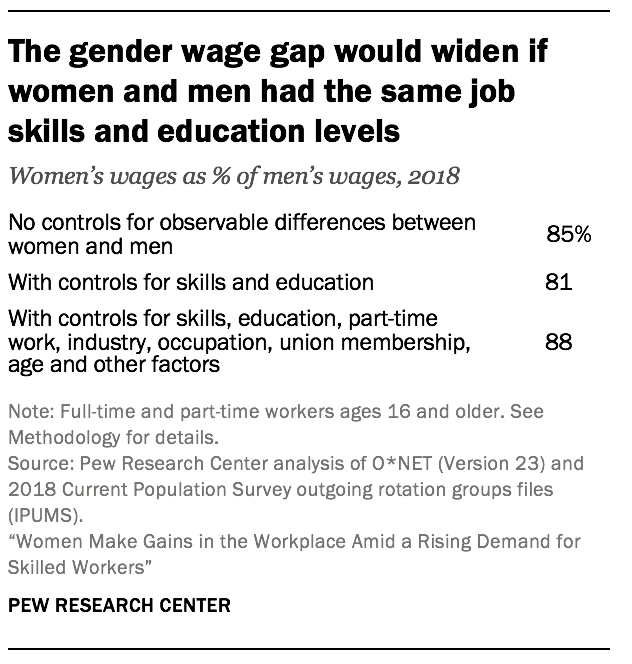

Like other research in the field, this analysis uses a statistical technique called regression analysis to determine the influence of factors such as skills and education on the size of the gender wage gap in 2018. As noted, women earned 85% as much as men in 2018, prior to accounting for any observed differences between women and men. The regression analysis is used to estimate the extent to which the 15-cent gap is related to the difference between women and men in skills and education level, part-time work, occupations, industries, and age, among other things.20(See Methodology.)

Among the factors analyzed, two are found to work to the benefit of women: their presence in high-skill jobs and their education level. Overall, women’s representation in higher-skill jobs is estimated to raise their earnings by 2 cents to the dollar in 2018 compared with men’s earnings. Women’s higher level of education also confers a benefit over men to the extent of 2 cents to the dollar. This means that if women were to lose their lead over men in skills and education their earnings would fall relative to the earnings of men, from 85% to 81%.

Among the factors analyzed, two are found to work to the benefit of women: their presence in high-skill jobs and their education level. Overall, women’s representation in higher-skill jobs is estimated to raise their earnings by 2 cents to the dollar in 2018 compared with men’s earnings. Women’s higher level of education also confers a benefit over men to the extent of 2 cents to the dollar. This means that if women were to lose their lead over men in skills and education their earnings would fall relative to the earnings of men, from 85% to 81%.

The factors that work to the detriment of women’s earnings include relatively more part-time work and disparities in occupations and industries of employment.21 The combined effect of these differences was to lower women’s wages by about 7 cents to the dollar in 2018 compared with men’s wages. Thus, if these disparities were to vanish, along with the gaps in skills and education, women’s earnings as a percent of men’s earnings would increase from 81% to 88%.

In summary, the overall effect of differences in skills, education, part-time work, industry, occupation and other observed factors is modest.22 Skills and education yield women a relative benefit of 4 cents for each dollar, but part-time work, industry, occupation and other factors give men an advantage of about 7 cents. The net effect is 3 cents in favor of men. This means that after accounting for observable differences in labor market attributes between women and men the gender wage gap is about 12 cents to the dollar, slightly narrower than 15 cents of the dollar, but shy of equality.