The share of U.S. women at the end of their childbearing years who have ever given birth was higher in 2016 than it had been 10 years earlier. Some 86% of women ages 40 to 44 are mothers, compared with 80% in 2006, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data.1 The share of women in this age group who are mothers is similar to what it was in the early 1990s.

Not only are women more likely to be mothers than in the past, but they are having more children. Overall, women have 2.07 children during their lives on average – up from 1.86 in 2006, the lowest number on record. And among those who are mothers, family size has also ticked up. In 2016, mothers at the end of their childbearing years had had about 2.42 children, compared with a low of 2.31 in 2008.

The recent rise in motherhood and fertility might seem to run counter to the notion that the U.S. is experiencing a post-recession “Baby Bust.” However, each trend is based on a different type of measurement. The analysis here is based on a cumulative measure of lifetime fertility, the number of births a woman has ever had; meantime, reports of declining U.S. fertility are based on annual rates, which capture fertility at one point in time.2

One factor driving down annual fertility rates is that women are becoming mothers later in life: The median age at which women become mothers in the U.S. is 26, compared with 23 in 1994. This change has been driven in part by declines in births to teens. In the mid-1990s, about one-in-five women in their early 40s (22%) had had a child prior to age 20; in 2014, that share had dropped to 13%. And delays in childbearing have continued among women in their 20s: While slightly more than half (53%) of women in their early 40s in 1994 had become mothers by age 24, this share was 39% among those who were in this age group in 2014.

The Great Recession intensified this shift toward later motherhood, which has been driven in the longer term by increases in educational attainment and women’s labor force participation, as well as delays in marriage. Given these social and cultural shifts, it seems likely that the postponement of childbearing will continue. But will the recent annual declines in fertility lead U.S. women to have smaller families in the future? It is difficult to know, but comparing the lifetime fertility of women who just recently completed their childbearing years with those 20 years earlier suggests that postponing births does not necessarily equate with lower lifetime fertility.

The majority of women ages 40 to 44 who have never married have had a baby

There has been a substantial increase in motherhood over the past two decades among women who have never married. As in the U.S. population as a whole, the share of women at the end of their childbearing years who have never wed has risen – from 9% in 1994 to 15% in 2014. Among these women, a majority (55%) have had at least one child. This marks a dramatic change from two decades earlier, when roughly a third (31%) of never-married women in their early 40s had given birth.3 At the same time, the share of women who become mothers among those who have been married remains high: 90% in 2014, compared with 88% in 1994.4

The upward trend in the share of never-married women having children is particularly striking given the overall falloff in births to teens in recent decades. While there has been an uptick in the share of never-married women in their early 40s who became mothers during their teenage years (from 11% to 15%), most of the growth in motherhood occurred at slightly older ages. For example, by age 29, 45% of never-married women in their early 40s in 2014 were moms, compared with 26% of their counterparts in 1994.

The share of never-married women in their early 40s who are mothers has risen across all educational levels as well. In fact, rates of motherhood have more than doubled for never-married women with some college experience as well as those with a bachelor’s degree or more education. For example, childlessness was almost universal among never-married women in their early 40s with a postgraduate degree in 1994, while in 2014 one-in-four comparable never-married women had a child. Still, despite the rapid gains in motherhood among never-married women with at least a bachelor’s degree, those with a high school diploma or less education remain more likely to be mothers: 70% are.

Motherhood rates have risen dramatically among white never-married women in their early 40s. In 2014, 37% were mothers, compared with just 13% two decades ago. Rates also ticked up among their black counterparts: 75% were mothers in 2014, compared with 69% in 1994.

Among women in their early 40s who have been married, the share that has given birth also has risen for those with a bachelor’s (from 83% to 89%) or postgraduate degree (from 80% to 88%). There has been no notable change in the share of ever-married women with less education who are mothers.

Biggest increases in motherhood among women with postgraduate degrees; shifts in timing evident across all educational groups

The share of all women ages 40 to 44 without a bachelor’s degree who are mothers has held steady over the past two decades while increasing among those with more education. As of 2014, 82% of women at the end of their childbearing years with a bachelor’s degree were mothers, compared with 76% of their counterparts in 1994. And while 79% of women in their early 40s who have a master’s degree also have at least one child, this share was 71% 20 years earlier. The most dramatic increase in motherhood has occurred among the relatively small group of women in their early 40s with a Ph.D. or professional degree, 80% of whom are mothers; among their predecessors, just 65% were.

The share of all women ages 40 to 44 without a bachelor’s degree who are mothers has held steady over the past two decades while increasing among those with more education. As of 2014, 82% of women at the end of their childbearing years with a bachelor’s degree were mothers, compared with 76% of their counterparts in 1994. And while 79% of women in their early 40s who have a master’s degree also have at least one child, this share was 71% 20 years earlier. The most dramatic increase in motherhood has occurred among the relatively small group of women in their early 40s with a Ph.D. or professional degree, 80% of whom are mothers; among their predecessors, just 65% were.

Across all levels of educational attainment, the timing of motherhood has shifted as a result of declines in first births to those in their teens, or to those in their early 20s.

Among women at the end of their childbearing years with a high school diploma or less education, 21% became mothers in their teens, 56% had done so by the time they were 24 and 75% were mothers by age 29. Among their counterparts in 1994, 31% had given birth prior to age 20, two-thirds had done so by age 24 and 81% were mothers by 29. Similarly, smaller shares of women in 2014 who were at the end of their childbearing years and had some college education had become mothers before age 20 (15%) than was the case in the mid-1990s, when the share stood at 20%. This delay in motherhood was more prominent by age 24 (45% vs. 56% in 1994) and had narrowed by age 29 (69% vs. 74%).

Women at the end of their childbearing years who have a college degree are also delaying motherhood well into their 20s. In 2014, about half (49%) of women in their early 40s with a bachelor’s degree had given birth by age 29, compared with 60% of their counterparts in 1994. By age 34, however, women who are at the end of their childbearing years had “caught up” to their predecessors: 72% of each group had become mothers by that age.

A somewhat different pattern emerges among women with advanced degrees who are at the end of their childbearing years. While they, too, were less likely to become mothers by the end of their 20s than their counterparts in 1994, in their 30s they became notably more likely to be moms than their predecessors. In 2014, 38% of women ages 40 to 44 with a master’s degree had become mothers by age 29 and 77% had become moms by 39. In comparison, 47% of women 40 to 44 in 1994 were mothers by age 29, and 71% were moms by the end of their 30s. And although at age 29 comparable women with a Ph.D. or professional degree were still less likely than their counterparts in 1994 to have had a baby (29% vs. 35%), by age 34 they were more likely to have done so (61% vs. 50%).

Women of all races and ethnicities delaying motherhood

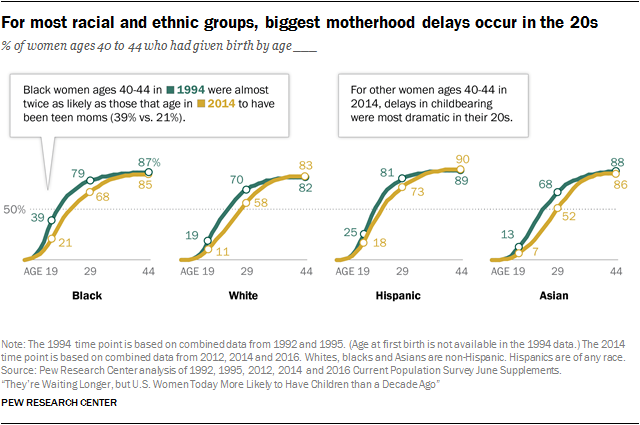

Among women who recently reached the end of their childbearing years, Hispanics are the most likely to have ever given birth: 90% have done so, compared with 85% of black women, 86% of Asian women and 83% of white women. This pattern is similar to that of women at the end of their childbearing years in the mid-1990s.

While there has been little change in recent decades in the shares of women who are mothers across racial and ethnic groups, the age at which women are becoming mothers has risen across all groups.

Among black women who recently finished their childbearing years, virtually all of the delay in motherhood originated in declines in teen motherhood. Some 21% of black women in their early 40s in 2014 had had a baby in their teens – a figure just over half that of their counterparts in 1994 (39%). To a lesser extent, the postponement in births that began in the teen years persisted at older ages: 68% had become mothers by the end of their 20s, compared with 79% among black women in their early 40s in 1994.

Among women in other racial and ethnic groups who were at the end of their childbearing years in 2014, the delays in motherhood were more pronounced in their 20s. A third of white women ages 40 to 44 had become mothers by age 24 and 58% had done so by age 29. Among their counterparts in 1994, half were moms by age 24, and 70% had given birth by age 29. Among Hispanic women, 53% of those who were in their early 40s in 2014 had become mothers by age 24 and 73% were moms by age 29. In comparison, 65% of their counterparts in 1994 were moms by 24 and 81% had given birth by the end of their 20s. Meanwhile, a quarter of Asian women who were in their early 40s in 2014 had become mothers by age 24 and 52% were mothers by the end of their 20s; in 1994, 43% were mothers by age 24, and 68% were mothers by age 29.

About the data

This report is based primarily on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s June Supplement of the Current Population Survey, which produces a nationally representative sample of the non-institutionalized population of the U.S. The June Fertility Supplement was first administered in 1976 and is typically conducted every other year. Public-use data files prior to 1986 are not readily available, so analyses of pre-1986 time points are drawn from Census Bureau tabulations.

The bulk of analyses in this report begin in the mid-1990s, because that is when the Census Bureau first began collecting detailed data on educational attainment.

Analyses looking at all women ages 40-44, or at all mothers ages 40-44, are based on data from single years. For detailed analyses by age at first birth, race and ethnicity, educational attainment and marital status, multiple years of data are combined to create sufficient sample sizes. Data from 1992, 1994 and 1995 are combined and referred to as “1994” for most of these analyses, and data from 2012, 2014 and 2016 are combined and referred to as “2014.” (Data from 1992 and 1995 are combined and referred to as “1994” for analyses related to age at first birth, since age at first birth was not collected in the 1994 survey.)

Even with combining years, there are some cases where sample sizes for some demographic groups were below 200, in which case results are not shown.

A working paper suggests that prior to 2012, when new editing protocols were implemented by the Census Bureau, the Current Population Survey may have overestimated childlessness somewhat. This makes it difficult to determine the exact magnitude of changes in childlessness across time, though simulations suggest that childlessness now is lower than it was around 10 years ago, and no higher than it was around the early 1990s, even taking the new editing protocol into account.

The phrases “in their early 40s,” “at the end of their childbearing years” and “ages 40 to 44” are used interchangeably to describe women in this report. Defining the end of the childbearing years as ages 40 to 44 has typically been the convention. This is partly due to the fact that few women have babies beyond these ages, and partly due to the fact that until recently, data on the completed fertility of women ages 45 and older were not typically collected. While technology is extending the age at which women can give birth, the vast majority still have children before age 45. In 2015, about 0.2% of first births occurred to women ages 45 or older, and Census Bureau estimates suggest that the share of women ages 40 to 44 who are childless does not differ from the share ages 44 to 50 who are childless.

The data used in these analyses are designed to assess women’s fertility, and as such a “mother” is here defined as any woman who has given birth. However, many women who do not bear their own children are indeed mothers. Estimates indicate that 6% of children with a parent householder in the U.S. are living with either an adoptive parent or a stepparent.

In the analysis by educational attainment, references to people with “high school or less” include those who have a high school diploma or its equivalent, such as a General Education Development (GED) certificate. “Some college” includes those with an associate degree and those who attended college but did not obtain a degree. References to respondents with “postgraduate” degrees include all people who have at least a master’s degree. Respondents with a “Ph.D./professional degree” include, for instance, those who have an M.D., a law degree or any type of doctorate degree.

References to whites, blacks and Asians include only those who are non-Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.