III. Marriage

About four-in-ten Americans think that marriage is on the rocks. No, not their marriage. The institution of marriage. In response to the question, "Some people say that the present institution of marriage is becoming obsolete—do you agree or disagree?" some 39% of survey respondents say they agree, while 58% disagree and 4% say they don't know.

As family historians[18. numoffset="16" See, for example, Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005. Pages 1-12.] have noted, observations about the fragility of marriage are as old and universal as marriage itself—meaning they've been around for thousands of years and permeated virtually every culture and corner of the globe.

Nevertheless, there's been a notable rise in recent decades in this country in the perception that marriage's best days are behind it. When this same question was posed on a 1978 survey, just 28% agreed with the premise.[19. This 1978 Time/Yankelovich, Skelly & White survey was among registered voters only. The “agree” response among registered voters in the 2010 survey was 36%.]

No matter what one thinks about the institution's future, there's no getting around its stark contraction during the past half century. Some 72% of all adults in the United States were married in 1960. By 2008, just 52% were.

Does this trend line lead inevitably to obsolescence? The notion that it does attracts some strange bedfellows—those who are contributing to the phenomenon (55% of cohabiters) as well as those who are most likely to be troubled by it (42% of self-described conservatives).

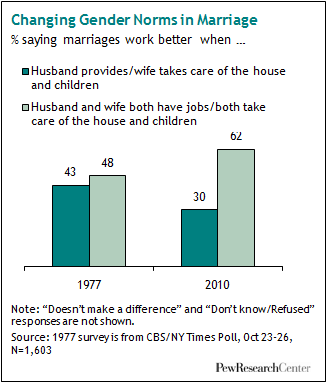

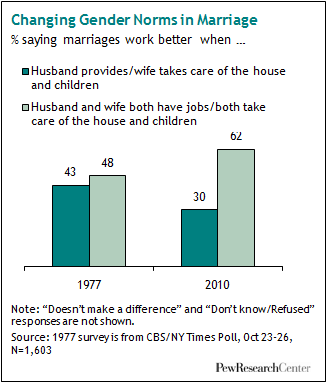

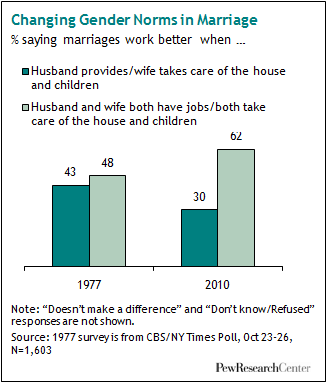

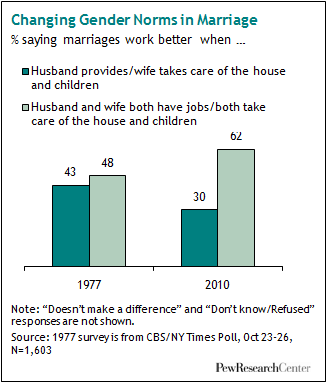

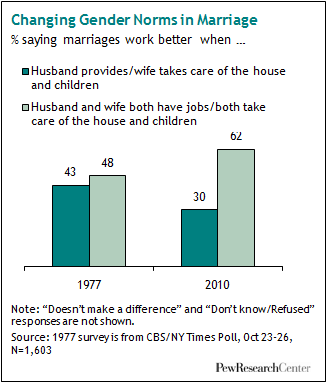

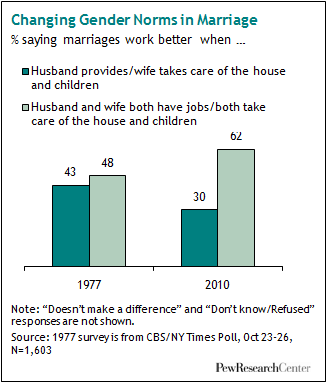

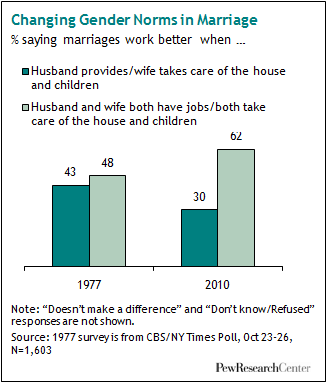

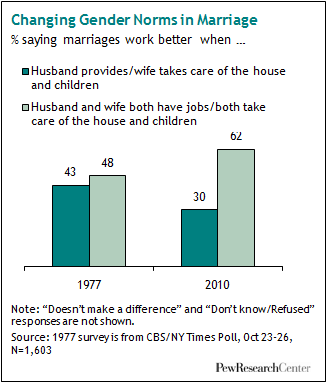

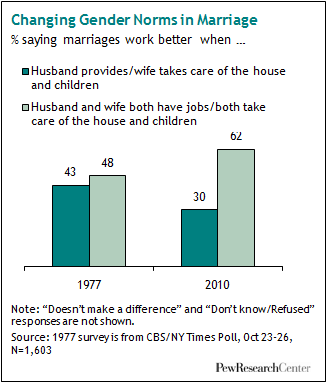

The survey reveals other intriguing cross-currents in the public's attitudes about marriage. For example, most Americans now embrace the ideal of gender equality between spouses. The mid-20

th century "Ozzie and Harriet" marriage between a breadwinner husband and a homemaker wife is now seen as the preferred model by just 30% of the public; some 62% say that marriages are better when husbands and wives both have jobs and both share responsibility for the household and kids.

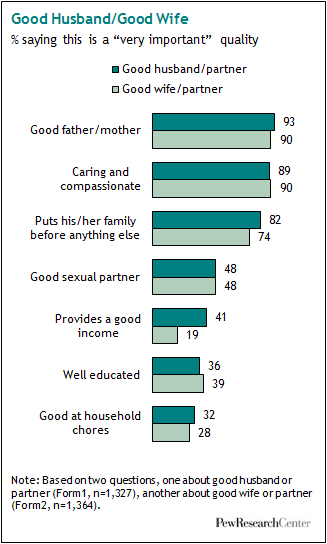

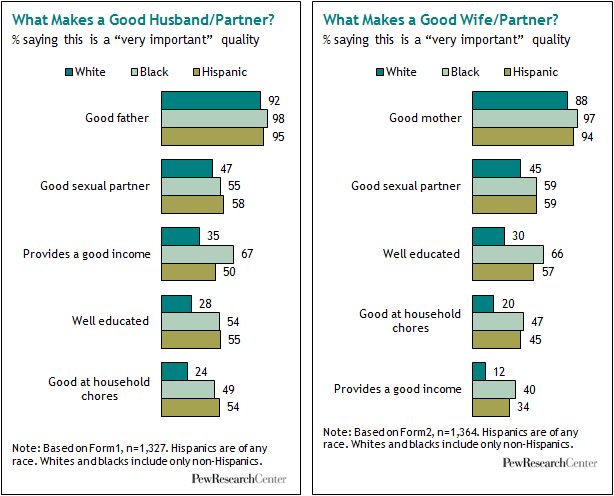

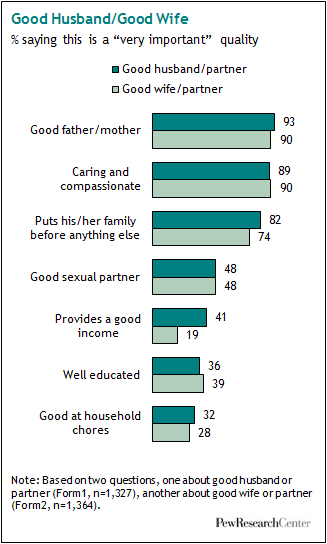

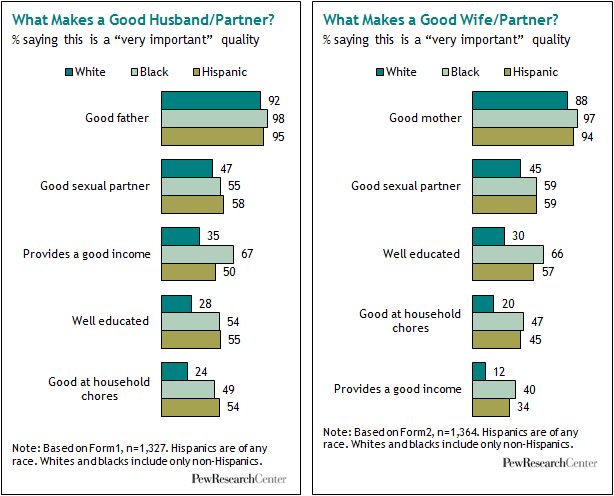

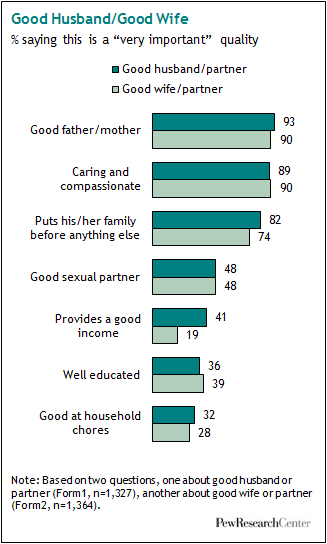

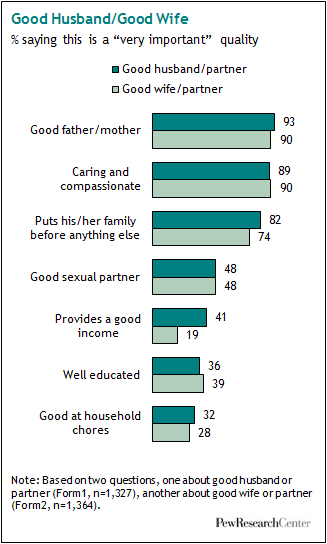

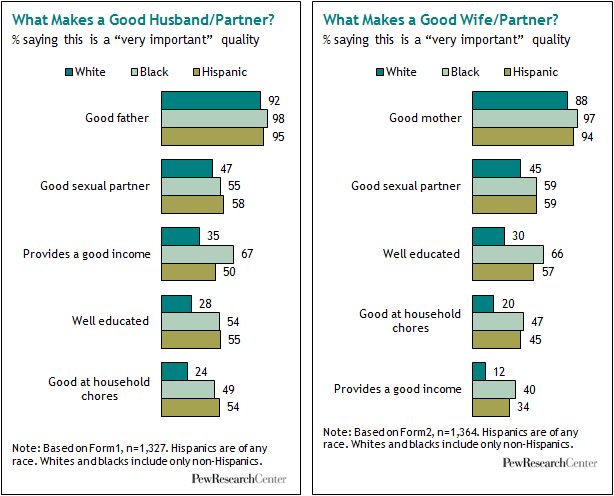

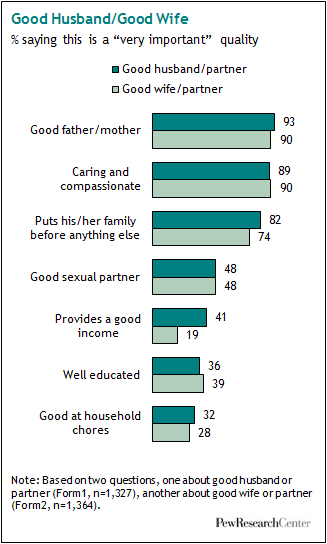

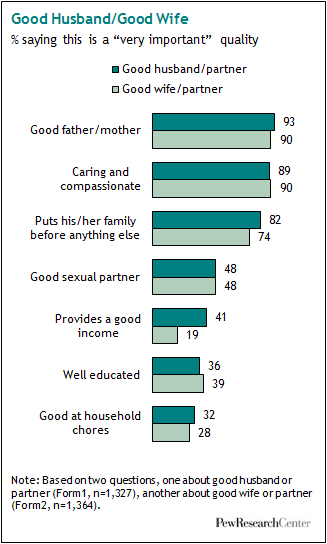

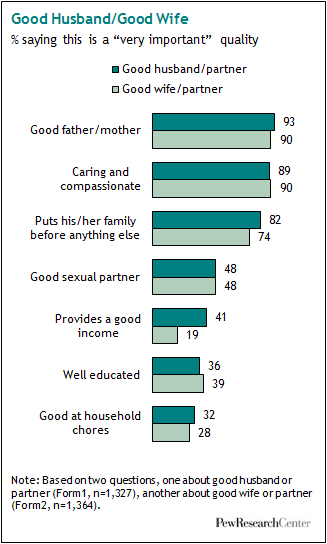

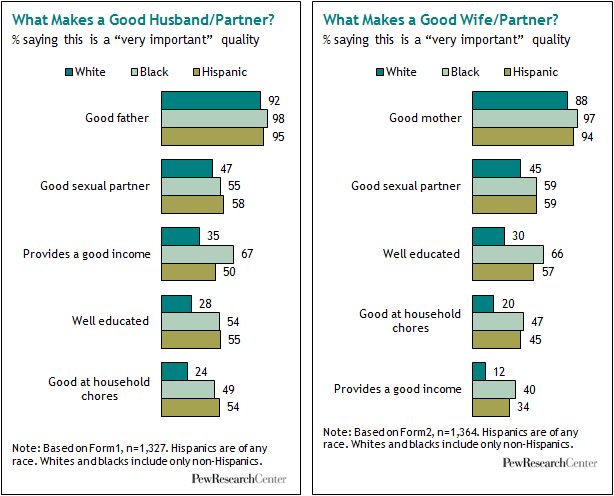

Even as public opinion embraces the ideal of spousal equality, however, it still hasn't given up the seemingly contradictory notion that men—far more than women—need to be good providers in order to be good marriage prospects. Two-thirds of survey respondents say this about men, while just one-third say it about women.

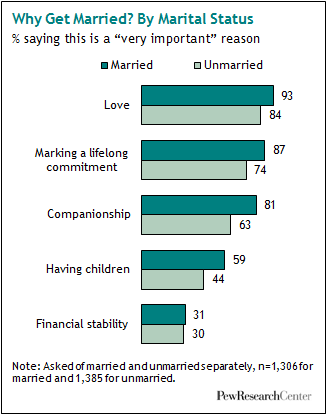

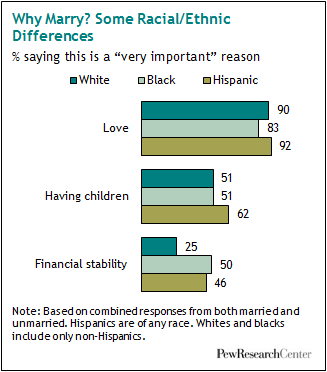

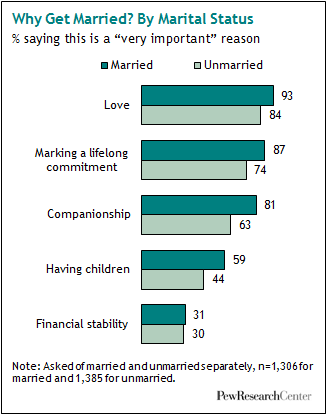

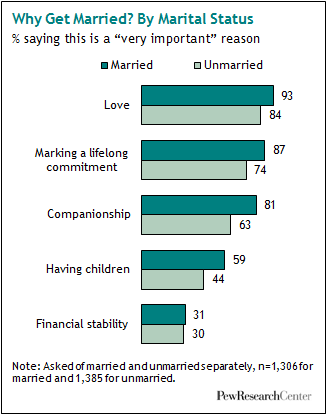

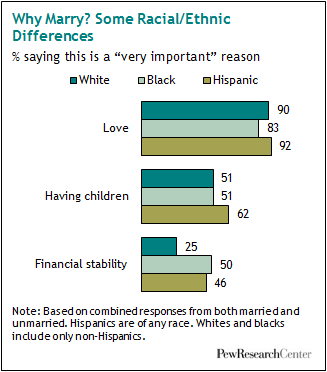

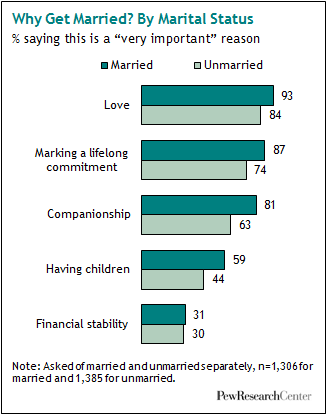

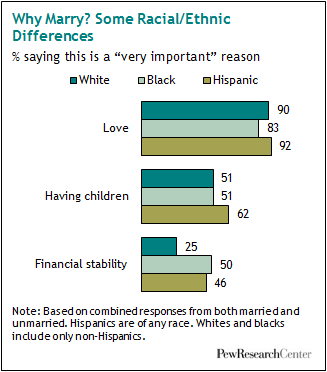

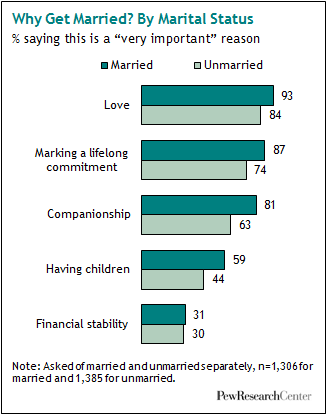

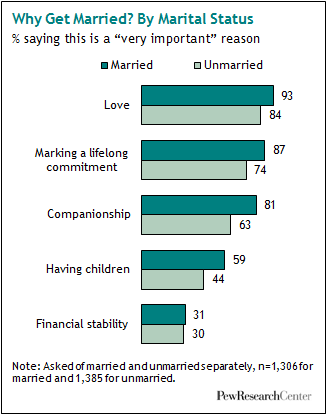

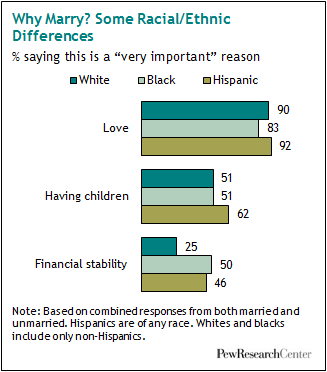

But comes now another wrinkle. To hear the public tell it, financial security isn't all that important to marriage. Asked to evaluate the reasons they got married, married respondents place the greatest value on love (93% say this is a very important reason), followed by making a lifelong commitment (87%), companionship (81%), having children (59%), and, at the bottom of the list, financial stability (31%). Unmarried adults order the reasons the same way when asked to evaluate why they would consider getting married.

The potency of the link between love and marriage is relatively new in the sweep of human history—and, in the view of some historians, a leading cause of the institution's decline.[20. Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005.] For several millennia, economic security was the

sine qua non of marriage. The institution thrived as an efficient way to divide labor, allocate resources, propagate the species and ensure that someone will take care of you when you get old. Only in recent centuries have love and mutual self-fulfillment come to occupy center stage in the grand marital bargain. But as the trends of the past half century attest, it's an open question whether a social institution built on love will prove as durable as one built on economic security.

Less Money, Less Marriage

About four-in-ten Americans think that marriage is on the rocks. No, not their marriage. The institution of marriage. In response to the question, "Some people say that the present institution of marriage is becoming obsolete—do you agree or disagree?" some 39% of survey respondents say they agree, while 58% disagree and 4% say they don't know.

As family historians[18. numoffset="16" See, for example, Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005. Pages 1-12.] have noted, observations about the fragility of marriage are as old and universal as marriage itself—meaning they've been around for thousands of years and permeated virtually every culture and corner of the globe.

Nevertheless, there's been a notable rise in recent decades in this country in the perception that marriage's best days are behind it. When this same question was posed on a 1978 survey, just 28% agreed with the premise.[19. This 1978 Time/Yankelovich, Skelly & White survey was among registered voters only. The “agree” response among registered voters in the 2010 survey was 36%.]

No matter what one thinks about the institution's future, there's no getting around its stark contraction during the past half century. Some 72% of all adults in the United States were married in 1960. By 2008, just 52% were.

Does this trend line lead inevitably to obsolescence? The notion that it does attracts some strange bedfellows—those who are contributing to the phenomenon (55% of cohabiters) as well as those who are most likely to be troubled by it (42% of self-described conservatives).

About four-in-ten Americans think that marriage is on the rocks. No, not their marriage. The institution of marriage. In response to the question, "Some people say that the present institution of marriage is becoming obsolete—do you agree or disagree?" some 39% of survey respondents say they agree, while 58% disagree and 4% say they don't know.

As family historians[18. numoffset="16" See, for example, Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005. Pages 1-12.] have noted, observations about the fragility of marriage are as old and universal as marriage itself—meaning they've been around for thousands of years and permeated virtually every culture and corner of the globe.

Nevertheless, there's been a notable rise in recent decades in this country in the perception that marriage's best days are behind it. When this same question was posed on a 1978 survey, just 28% agreed with the premise.[19. This 1978 Time/Yankelovich, Skelly & White survey was among registered voters only. The “agree” response among registered voters in the 2010 survey was 36%.]

No matter what one thinks about the institution's future, there's no getting around its stark contraction during the past half century. Some 72% of all adults in the United States were married in 1960. By 2008, just 52% were.

Does this trend line lead inevitably to obsolescence? The notion that it does attracts some strange bedfellows—those who are contributing to the phenomenon (55% of cohabiters) as well as those who are most likely to be troubled by it (42% of self-described conservatives).

The survey reveals other intriguing cross-currents in the public's attitudes about marriage. For example, most Americans now embrace the ideal of gender equality between spouses. The mid-20th century "Ozzie and Harriet" marriage between a breadwinner husband and a homemaker wife is now seen as the preferred model by just 30% of the public; some 62% say that marriages are better when husbands and wives both have jobs and both share responsibility for the household and kids.

The survey reveals other intriguing cross-currents in the public's attitudes about marriage. For example, most Americans now embrace the ideal of gender equality between spouses. The mid-20th century "Ozzie and Harriet" marriage between a breadwinner husband and a homemaker wife is now seen as the preferred model by just 30% of the public; some 62% say that marriages are better when husbands and wives both have jobs and both share responsibility for the household and kids.

Even as public opinion embraces the ideal of spousal equality, however, it still hasn't given up the seemingly contradictory notion that men—far more than women—need to be good providers in order to be good marriage prospects. Two-thirds of survey respondents say this about men, while just one-third say it about women.

But comes now another wrinkle. To hear the public tell it, financial security isn't all that important to marriage. Asked to evaluate the reasons they got married, married respondents place the greatest value on love (93% say this is a very important reason), followed by making a lifelong commitment (87%), companionship (81%), having children (59%), and, at the bottom of the list, financial stability (31%). Unmarried adults order the reasons the same way when asked to evaluate why they would consider getting married.

The potency of the link between love and marriage is relatively new in the sweep of human history—and, in the view of some historians, a leading cause of the institution's decline.[20. Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005.] For several millennia, economic security was the sine qua non of marriage. The institution thrived as an efficient way to divide labor, allocate resources, propagate the species and ensure that someone will take care of you when you get old. Only in recent centuries have love and mutual self-fulfillment come to occupy center stage in the grand marital bargain. But as the trends of the past half century attest, it's an open question whether a social institution built on love will prove as durable as one built on economic security.

Even as public opinion embraces the ideal of spousal equality, however, it still hasn't given up the seemingly contradictory notion that men—far more than women—need to be good providers in order to be good marriage prospects. Two-thirds of survey respondents say this about men, while just one-third say it about women.

But comes now another wrinkle. To hear the public tell it, financial security isn't all that important to marriage. Asked to evaluate the reasons they got married, married respondents place the greatest value on love (93% say this is a very important reason), followed by making a lifelong commitment (87%), companionship (81%), having children (59%), and, at the bottom of the list, financial stability (31%). Unmarried adults order the reasons the same way when asked to evaluate why they would consider getting married.

The potency of the link between love and marriage is relatively new in the sweep of human history—and, in the view of some historians, a leading cause of the institution's decline.[20. Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005.] For several millennia, economic security was the sine qua non of marriage. The institution thrived as an efficient way to divide labor, allocate resources, propagate the species and ensure that someone will take care of you when you get old. Only in recent centuries have love and mutual self-fulfillment come to occupy center stage in the grand marital bargain. But as the trends of the past half century attest, it's an open question whether a social institution built on love will prove as durable as one built on economic security.

Less Money, Less Marriage

If economic security is no longer a key reason people marry, the lack of economic security nonetheless appears to be a key reason people don't get married. As noted in the overview of this report, 50 years ago there was virtually no difference by socio-economic status in the proclivity to marry: 76% of college graduates and 72% of adults who did not attend college were married in 1960. By 2008, that small gap had widened to a chasm: 64% of college graduates were married, compared with just 48% of those with a high school diploma or less. During this same period, the income gap between the well-educated and the less-educated—and between the rich and poor—also widened substantially.[21. See for instance “Changes in Income Inequality across the U.S.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Sep 21, 2007.]

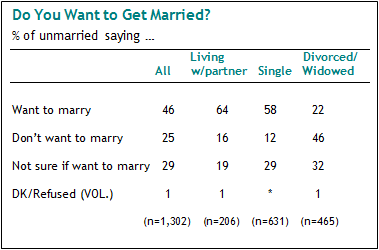

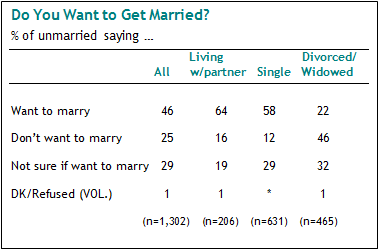

The 2010 Pew Research survey finds that among the unmarried, there are no significant differences by education or income in the desire to get married; just under half of the college educated (46%) and those who have a high school diploma or less (44%) would like to get married. Likewise, roughly similar shares of the unmarried who earn above and below $100,000 a year would like to marry.

But the survey also finds that the less education and income people have, the more likely they are to say that in order to be a good marriage prospect, a person must be able to support a family financially. Taken together, these findings suggest that those with less income and education are opting out of marriage not because they don't value the institution or aspire to it benefits, but because they may doubt that they (or a potential spouse) can meet the standards they impose on marriage.

The Upsides of Marriage

About four-in-ten Americans think that marriage is on the rocks. No, not their marriage. The institution of marriage. In response to the question, "Some people say that the present institution of marriage is becoming obsolete—do you agree or disagree?" some 39% of survey respondents say they agree, while 58% disagree and 4% say they don't know.

As family historians[18. numoffset="16" See, for example, Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005. Pages 1-12.] have noted, observations about the fragility of marriage are as old and universal as marriage itself—meaning they've been around for thousands of years and permeated virtually every culture and corner of the globe.

Nevertheless, there's been a notable rise in recent decades in this country in the perception that marriage's best days are behind it. When this same question was posed on a 1978 survey, just 28% agreed with the premise.[19. This 1978 Time/Yankelovich, Skelly & White survey was among registered voters only. The “agree” response among registered voters in the 2010 survey was 36%.]

No matter what one thinks about the institution's future, there's no getting around its stark contraction during the past half century. Some 72% of all adults in the United States were married in 1960. By 2008, just 52% were.

Does this trend line lead inevitably to obsolescence? The notion that it does attracts some strange bedfellows—those who are contributing to the phenomenon (55% of cohabiters) as well as those who are most likely to be troubled by it (42% of self-described conservatives).

About four-in-ten Americans think that marriage is on the rocks. No, not their marriage. The institution of marriage. In response to the question, "Some people say that the present institution of marriage is becoming obsolete—do you agree or disagree?" some 39% of survey respondents say they agree, while 58% disagree and 4% say they don't know.

As family historians[18. numoffset="16" See, for example, Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005. Pages 1-12.] have noted, observations about the fragility of marriage are as old and universal as marriage itself—meaning they've been around for thousands of years and permeated virtually every culture and corner of the globe.

Nevertheless, there's been a notable rise in recent decades in this country in the perception that marriage's best days are behind it. When this same question was posed on a 1978 survey, just 28% agreed with the premise.[19. This 1978 Time/Yankelovich, Skelly & White survey was among registered voters only. The “agree” response among registered voters in the 2010 survey was 36%.]

No matter what one thinks about the institution's future, there's no getting around its stark contraction during the past half century. Some 72% of all adults in the United States were married in 1960. By 2008, just 52% were.

Does this trend line lead inevitably to obsolescence? The notion that it does attracts some strange bedfellows—those who are contributing to the phenomenon (55% of cohabiters) as well as those who are most likely to be troubled by it (42% of self-described conservatives).

The survey reveals other intriguing cross-currents in the public's attitudes about marriage. For example, most Americans now embrace the ideal of gender equality between spouses. The mid-20th century "Ozzie and Harriet" marriage between a breadwinner husband and a homemaker wife is now seen as the preferred model by just 30% of the public; some 62% say that marriages are better when husbands and wives both have jobs and both share responsibility for the household and kids.

The survey reveals other intriguing cross-currents in the public's attitudes about marriage. For example, most Americans now embrace the ideal of gender equality between spouses. The mid-20th century "Ozzie and Harriet" marriage between a breadwinner husband and a homemaker wife is now seen as the preferred model by just 30% of the public; some 62% say that marriages are better when husbands and wives both have jobs and both share responsibility for the household and kids.

Even as public opinion embraces the ideal of spousal equality, however, it still hasn't given up the seemingly contradictory notion that men—far more than women—need to be good providers in order to be good marriage prospects. Two-thirds of survey respondents say this about men, while just one-third say it about women.

But comes now another wrinkle. To hear the public tell it, financial security isn't all that important to marriage. Asked to evaluate the reasons they got married, married respondents place the greatest value on love (93% say this is a very important reason), followed by making a lifelong commitment (87%), companionship (81%), having children (59%), and, at the bottom of the list, financial stability (31%). Unmarried adults order the reasons the same way when asked to evaluate why they would consider getting married.

The potency of the link between love and marriage is relatively new in the sweep of human history—and, in the view of some historians, a leading cause of the institution's decline.[20. Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005.] For several millennia, economic security was the sine qua non of marriage. The institution thrived as an efficient way to divide labor, allocate resources, propagate the species and ensure that someone will take care of you when you get old. Only in recent centuries have love and mutual self-fulfillment come to occupy center stage in the grand marital bargain. But as the trends of the past half century attest, it's an open question whether a social institution built on love will prove as durable as one built on economic security.

Even as public opinion embraces the ideal of spousal equality, however, it still hasn't given up the seemingly contradictory notion that men—far more than women—need to be good providers in order to be good marriage prospects. Two-thirds of survey respondents say this about men, while just one-third say it about women.

But comes now another wrinkle. To hear the public tell it, financial security isn't all that important to marriage. Asked to evaluate the reasons they got married, married respondents place the greatest value on love (93% say this is a very important reason), followed by making a lifelong commitment (87%), companionship (81%), having children (59%), and, at the bottom of the list, financial stability (31%). Unmarried adults order the reasons the same way when asked to evaluate why they would consider getting married.

The potency of the link between love and marriage is relatively new in the sweep of human history—and, in the view of some historians, a leading cause of the institution's decline.[20. Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005.] For several millennia, economic security was the sine qua non of marriage. The institution thrived as an efficient way to divide labor, allocate resources, propagate the species and ensure that someone will take care of you when you get old. Only in recent centuries have love and mutual self-fulfillment come to occupy center stage in the grand marital bargain. But as the trends of the past half century attest, it's an open question whether a social institution built on love will prove as durable as one built on economic security.

Less Money, Less Marriage

If economic security is no longer a key reason people marry, the lack of economic security nonetheless appears to be a key reason people don't get married. As noted in the overview of this report, 50 years ago there was virtually no difference by socio-economic status in the proclivity to marry: 76% of college graduates and 72% of adults who did not attend college were married in 1960. By 2008, that small gap had widened to a chasm: 64% of college graduates were married, compared with just 48% of those with a high school diploma or less. During this same period, the income gap between the well-educated and the less-educated—and between the rich and poor—also widened substantially.[21. See for instance “Changes in Income Inequality across the U.S.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Sep 21, 2007.]

The 2010 Pew Research survey finds that among the unmarried, there are no significant differences by education or income in the desire to get married; just under half of the college educated (46%) and those who have a high school diploma or less (44%) would like to get married. Likewise, roughly similar shares of the unmarried who earn above and below $100,000 a year would like to marry.

But the survey also finds that the less education and income people have, the more likely they are to say that in order to be a good marriage prospect, a person must be able to support a family financially. Taken together, these findings suggest that those with less income and education are opting out of marriage not because they don't value the institution or aspire to it benefits, but because they may doubt that they (or a potential spouse) can meet the standards they impose on marriage.

The Upsides of Marriage

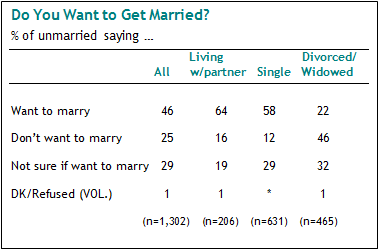

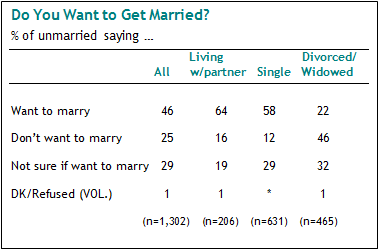

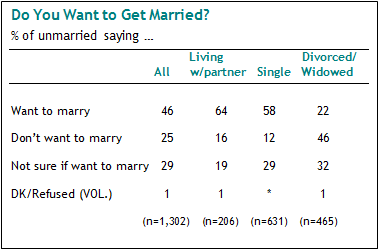

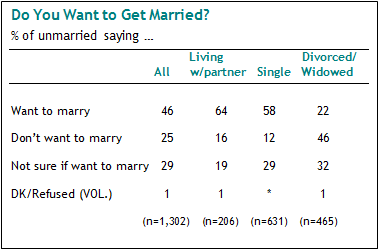

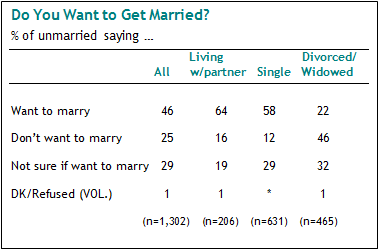

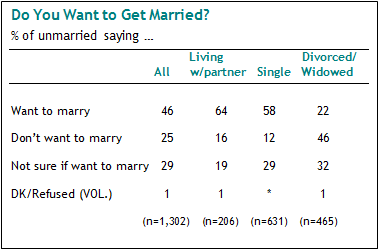

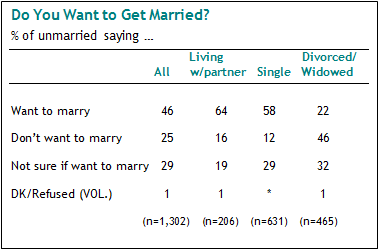

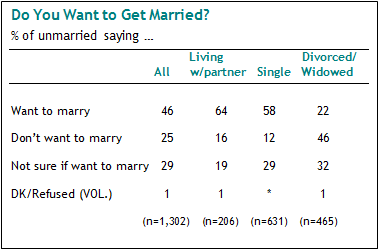

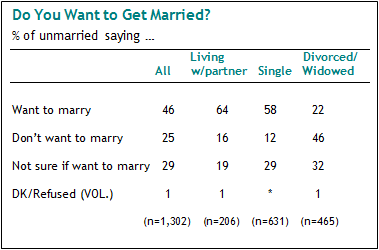

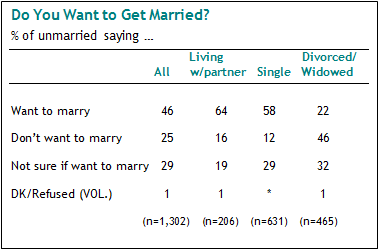

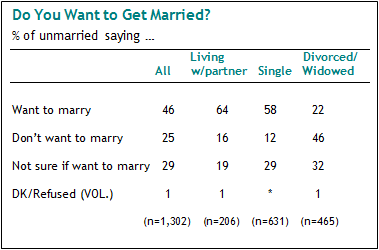

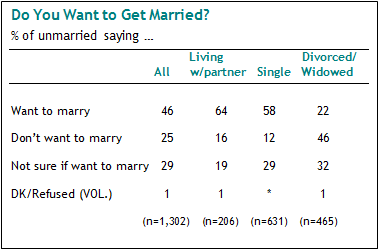

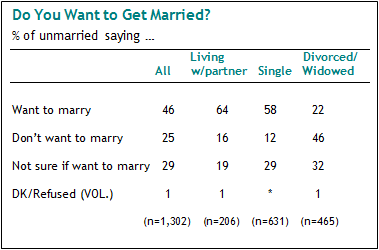

Not all of the survey findings are harbingers of gloom and doom for the institution of marriage. Even among those who are not currently married, getting hitched continues to have appeal. A plurality of 46% of those who are not married say they would like to marry, while three-in-ten (29%) say they are not sure. Just one-in-four say they don't want to marry.

Not all of the survey findings are harbingers of gloom and doom for the institution of marriage. Even among those who are not currently married, getting hitched continues to have appeal. A plurality of 46% of those who are not married say they would like to marry, while three-in-ten (29%) say they are not sure. Just one-in-four say they don't want to marry.

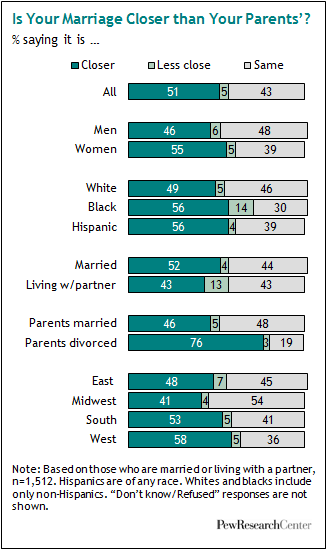

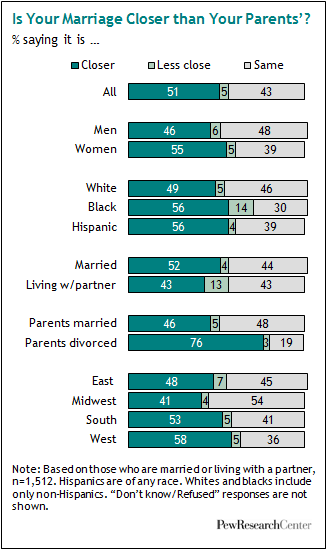

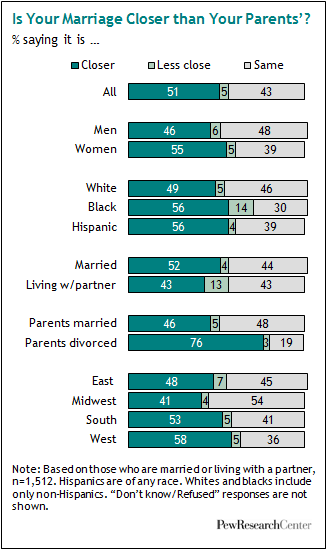

Moreover, marriage may have been more prevalent a generation ago, but most married or cohabiting respondents today believe their own relationship compares favorably with their parents'. Some 51% say they have a closer relationship with their spouse or partner than their parents had with each other, while just 5% characterize their own relationship as less close. The remainder—43%—say there is no difference.

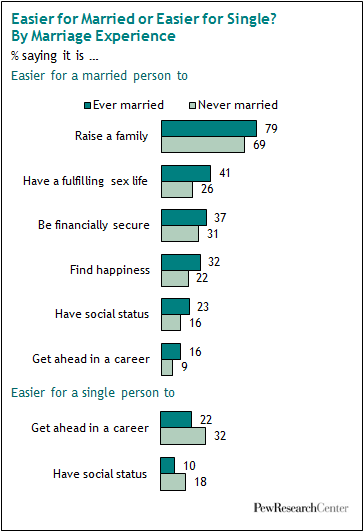

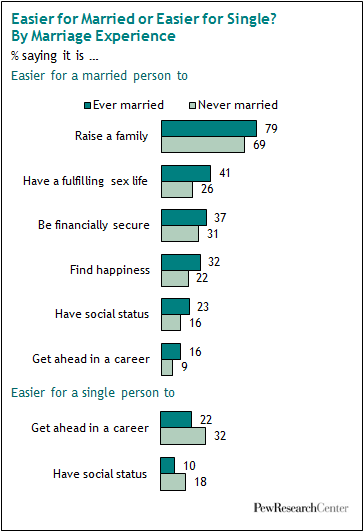

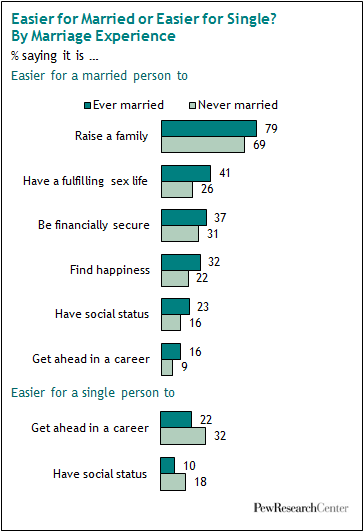

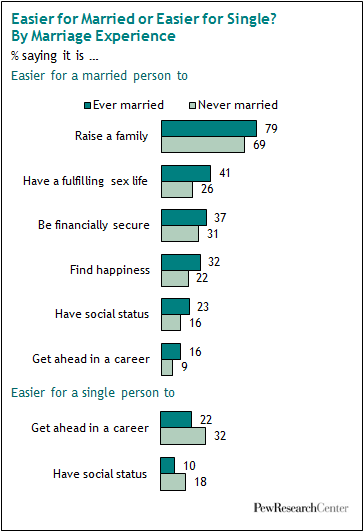

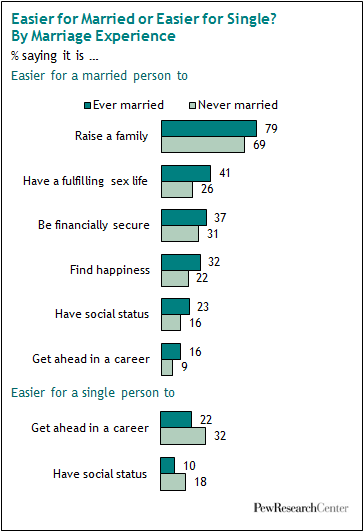

A majority of adults believe that in many key realms of life—such as finding happiness, getting ahead in a career or having social status—it doesn't make any difference whether a person is married or single. However, among those who believe it does make a difference, most say that being married is better.

For example, when it comes to being financially secure, 35% of respondents believe this is easier to do as a married person, while 11% say it is easier for a single person and half say it makes no difference. Similar patterns emerge for having a fulfilling sexual life, finding happiness and having social status. The two outliers from this pattern are raising a family (fully 77% say this is easier for a married person) and getting ahead in a career (just 14% say this is easier for a married person, compared with 24% who say it is easier for a single person).

Finally, a classic question about love was posed in the survey: Do you agree or disagree that there is only one true love for each person? Nearly three-in-ten (28%) Americans agree, while 69% disagree. Among the minority who believe in just one true love, 79% say—in response to a follow-up question—that they've found theirs. And among those in this group who are married, 96% say they've found theirs—meaning that virtually all are either deeply committed or very careful with their words.

The remainder of this chapter examines all of these questions in depth and explores the demographic patterns in attitudes and behaviors related to marriage.

Moreover, marriage may have been more prevalent a generation ago, but most married or cohabiting respondents today believe their own relationship compares favorably with their parents'. Some 51% say they have a closer relationship with their spouse or partner than their parents had with each other, while just 5% characterize their own relationship as less close. The remainder—43%—say there is no difference.

A majority of adults believe that in many key realms of life—such as finding happiness, getting ahead in a career or having social status—it doesn't make any difference whether a person is married or single. However, among those who believe it does make a difference, most say that being married is better.

For example, when it comes to being financially secure, 35% of respondents believe this is easier to do as a married person, while 11% say it is easier for a single person and half say it makes no difference. Similar patterns emerge for having a fulfilling sexual life, finding happiness and having social status. The two outliers from this pattern are raising a family (fully 77% say this is easier for a married person) and getting ahead in a career (just 14% say this is easier for a married person, compared with 24% who say it is easier for a single person).

Finally, a classic question about love was posed in the survey: Do you agree or disagree that there is only one true love for each person? Nearly three-in-ten (28%) Americans agree, while 69% disagree. Among the minority who believe in just one true love, 79% say—in response to a follow-up question—that they've found theirs. And among those in this group who are married, 96% say they've found theirs—meaning that virtually all are either deeply committed or very careful with their words.

The remainder of this chapter examines all of these questions in depth and explores the demographic patterns in attitudes and behaviors related to marriage.

Is Marriage Becoming Obsolete?

About four-in-ten Americans think that marriage is on the rocks. No, not their marriage. The institution of marriage. In response to the question, "Some people say that the present institution of marriage is becoming obsolete—do you agree or disagree?" some 39% of survey respondents say they agree, while 58% disagree and 4% say they don't know.

As family historians[18. numoffset="16" See, for example, Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005. Pages 1-12.] have noted, observations about the fragility of marriage are as old and universal as marriage itself—meaning they've been around for thousands of years and permeated virtually every culture and corner of the globe.

Nevertheless, there's been a notable rise in recent decades in this country in the perception that marriage's best days are behind it. When this same question was posed on a 1978 survey, just 28% agreed with the premise.[19. This 1978 Time/Yankelovich, Skelly & White survey was among registered voters only. The “agree” response among registered voters in the 2010 survey was 36%.]

No matter what one thinks about the institution's future, there's no getting around its stark contraction during the past half century. Some 72% of all adults in the United States were married in 1960. By 2008, just 52% were.

Does this trend line lead inevitably to obsolescence? The notion that it does attracts some strange bedfellows—those who are contributing to the phenomenon (55% of cohabiters) as well as those who are most likely to be troubled by it (42% of self-described conservatives).

About four-in-ten Americans think that marriage is on the rocks. No, not their marriage. The institution of marriage. In response to the question, "Some people say that the present institution of marriage is becoming obsolete—do you agree or disagree?" some 39% of survey respondents say they agree, while 58% disagree and 4% say they don't know.

As family historians[18. numoffset="16" See, for example, Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005. Pages 1-12.] have noted, observations about the fragility of marriage are as old and universal as marriage itself—meaning they've been around for thousands of years and permeated virtually every culture and corner of the globe.

Nevertheless, there's been a notable rise in recent decades in this country in the perception that marriage's best days are behind it. When this same question was posed on a 1978 survey, just 28% agreed with the premise.[19. This 1978 Time/Yankelovich, Skelly & White survey was among registered voters only. The “agree” response among registered voters in the 2010 survey was 36%.]

No matter what one thinks about the institution's future, there's no getting around its stark contraction during the past half century. Some 72% of all adults in the United States were married in 1960. By 2008, just 52% were.

Does this trend line lead inevitably to obsolescence? The notion that it does attracts some strange bedfellows—those who are contributing to the phenomenon (55% of cohabiters) as well as those who are most likely to be troubled by it (42% of self-described conservatives).

The survey reveals other intriguing cross-currents in the public's attitudes about marriage. For example, most Americans now embrace the ideal of gender equality between spouses. The mid-20th century "Ozzie and Harriet" marriage between a breadwinner husband and a homemaker wife is now seen as the preferred model by just 30% of the public; some 62% say that marriages are better when husbands and wives both have jobs and both share responsibility for the household and kids.

The survey reveals other intriguing cross-currents in the public's attitudes about marriage. For example, most Americans now embrace the ideal of gender equality between spouses. The mid-20th century "Ozzie and Harriet" marriage between a breadwinner husband and a homemaker wife is now seen as the preferred model by just 30% of the public; some 62% say that marriages are better when husbands and wives both have jobs and both share responsibility for the household and kids.

Even as public opinion embraces the ideal of spousal equality, however, it still hasn't given up the seemingly contradictory notion that men—far more than women—need to be good providers in order to be good marriage prospects. Two-thirds of survey respondents say this about men, while just one-third say it about women.

But comes now another wrinkle. To hear the public tell it, financial security isn't all that important to marriage. Asked to evaluate the reasons they got married, married respondents place the greatest value on love (93% say this is a very important reason), followed by making a lifelong commitment (87%), companionship (81%), having children (59%), and, at the bottom of the list, financial stability (31%). Unmarried adults order the reasons the same way when asked to evaluate why they would consider getting married.

The potency of the link between love and marriage is relatively new in the sweep of human history—and, in the view of some historians, a leading cause of the institution's decline.[20. Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005.] For several millennia, economic security was the sine qua non of marriage. The institution thrived as an efficient way to divide labor, allocate resources, propagate the species and ensure that someone will take care of you when you get old. Only in recent centuries have love and mutual self-fulfillment come to occupy center stage in the grand marital bargain. But as the trends of the past half century attest, it's an open question whether a social institution built on love will prove as durable as one built on economic security.

Even as public opinion embraces the ideal of spousal equality, however, it still hasn't given up the seemingly contradictory notion that men—far more than women—need to be good providers in order to be good marriage prospects. Two-thirds of survey respondents say this about men, while just one-third say it about women.

But comes now another wrinkle. To hear the public tell it, financial security isn't all that important to marriage. Asked to evaluate the reasons they got married, married respondents place the greatest value on love (93% say this is a very important reason), followed by making a lifelong commitment (87%), companionship (81%), having children (59%), and, at the bottom of the list, financial stability (31%). Unmarried adults order the reasons the same way when asked to evaluate why they would consider getting married.

The potency of the link between love and marriage is relatively new in the sweep of human history—and, in the view of some historians, a leading cause of the institution's decline.[20. Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005.] For several millennia, economic security was the sine qua non of marriage. The institution thrived as an efficient way to divide labor, allocate resources, propagate the species and ensure that someone will take care of you when you get old. Only in recent centuries have love and mutual self-fulfillment come to occupy center stage in the grand marital bargain. But as the trends of the past half century attest, it's an open question whether a social institution built on love will prove as durable as one built on economic security.

Less Money, Less Marriage

If economic security is no longer a key reason people marry, the lack of economic security nonetheless appears to be a key reason people don't get married. As noted in the overview of this report, 50 years ago there was virtually no difference by socio-economic status in the proclivity to marry: 76% of college graduates and 72% of adults who did not attend college were married in 1960. By 2008, that small gap had widened to a chasm: 64% of college graduates were married, compared with just 48% of those with a high school diploma or less. During this same period, the income gap between the well-educated and the less-educated—and between the rich and poor—also widened substantially.[21. See for instance “Changes in Income Inequality across the U.S.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Sep 21, 2007.]

The 2010 Pew Research survey finds that among the unmarried, there are no significant differences by education or income in the desire to get married; just under half of the college educated (46%) and those who have a high school diploma or less (44%) would like to get married. Likewise, roughly similar shares of the unmarried who earn above and below $100,000 a year would like to marry.

But the survey also finds that the less education and income people have, the more likely they are to say that in order to be a good marriage prospect, a person must be able to support a family financially. Taken together, these findings suggest that those with less income and education are opting out of marriage not because they don't value the institution or aspire to it benefits, but because they may doubt that they (or a potential spouse) can meet the standards they impose on marriage.

The Upsides of Marriage

Not all of the survey findings are harbingers of gloom and doom for the institution of marriage. Even among those who are not currently married, getting hitched continues to have appeal. A plurality of 46% of those who are not married say they would like to marry, while three-in-ten (29%) say they are not sure. Just one-in-four say they don't want to marry.

Not all of the survey findings are harbingers of gloom and doom for the institution of marriage. Even among those who are not currently married, getting hitched continues to have appeal. A plurality of 46% of those who are not married say they would like to marry, while three-in-ten (29%) say they are not sure. Just one-in-four say they don't want to marry.

Moreover, marriage may have been more prevalent a generation ago, but most married or cohabiting respondents today believe their own relationship compares favorably with their parents'. Some 51% say they have a closer relationship with their spouse or partner than their parents had with each other, while just 5% characterize their own relationship as less close. The remainder—43%—say there is no difference.

A majority of adults believe that in many key realms of life—such as finding happiness, getting ahead in a career or having social status—it doesn't make any difference whether a person is married or single. However, among those who believe it does make a difference, most say that being married is better.

For example, when it comes to being financially secure, 35% of respondents believe this is easier to do as a married person, while 11% say it is easier for a single person and half say it makes no difference. Similar patterns emerge for having a fulfilling sexual life, finding happiness and having social status. The two outliers from this pattern are raising a family (fully 77% say this is easier for a married person) and getting ahead in a career (just 14% say this is easier for a married person, compared with 24% who say it is easier for a single person).

Finally, a classic question about love was posed in the survey: Do you agree or disagree that there is only one true love for each person? Nearly three-in-ten (28%) Americans agree, while 69% disagree. Among the minority who believe in just one true love, 79% say—in response to a follow-up question—that they've found theirs. And among those in this group who are married, 96% say they've found theirs—meaning that virtually all are either deeply committed or very careful with their words.

The remainder of this chapter examines all of these questions in depth and explores the demographic patterns in attitudes and behaviors related to marriage.

Moreover, marriage may have been more prevalent a generation ago, but most married or cohabiting respondents today believe their own relationship compares favorably with their parents'. Some 51% say they have a closer relationship with their spouse or partner than their parents had with each other, while just 5% characterize their own relationship as less close. The remainder—43%—say there is no difference.

A majority of adults believe that in many key realms of life—such as finding happiness, getting ahead in a career or having social status—it doesn't make any difference whether a person is married or single. However, among those who believe it does make a difference, most say that being married is better.

For example, when it comes to being financially secure, 35% of respondents believe this is easier to do as a married person, while 11% say it is easier for a single person and half say it makes no difference. Similar patterns emerge for having a fulfilling sexual life, finding happiness and having social status. The two outliers from this pattern are raising a family (fully 77% say this is easier for a married person) and getting ahead in a career (just 14% say this is easier for a married person, compared with 24% who say it is easier for a single person).

Finally, a classic question about love was posed in the survey: Do you agree or disagree that there is only one true love for each person? Nearly three-in-ten (28%) Americans agree, while 69% disagree. Among the minority who believe in just one true love, 79% say—in response to a follow-up question—that they've found theirs. And among those in this group who are married, 96% say they've found theirs—meaning that virtually all are either deeply committed or very careful with their words.

The remainder of this chapter examines all of these questions in depth and explores the demographic patterns in attitudes and behaviors related to marriage.

Is Marriage Becoming Obsolete?

It's no small thing when nearly four-in-ten (39%) Americans agree that the world's most enduring social institution is becoming obsolete. Nonetheless, this finding needs to be interpreted with caution.

For one thing, "becoming obsolete" is not the same as "obsolete." When the World Values Survey posed a similar question in 2006 that used a more starkly worded formulation ("Marriage is an outdated institution—agree or disagree?"), just 13% of American respondents agreed.

In addition, respondents who doubt the durability of marriage appear to include a mix of those who are comfortable with the change and those who are troubled by it.

Among the demographic groups most likely to agree that marriage is becoming obsolete are the young (44% of 18- to 29-year-olds say this), blacks (44%), those who have a high school diploma or less (45%) and those whose annual income is less than $30,000 (48%). All of these groups are less likely than their demographic opposites (older, white, college educated, higher income) to be married—and thus their judgments could well be shaped to some degree by their life experiences.

These differences come into sharper focus when one looks specifically at respondents' marital status. Just 31% of married adults agree that marriage is becoming obsolete, compared with 46% of all unmarried adults, 58% of all single parents and 62% of all cohabiting (but unmarried) parents.

But it's not just those who are living out alternative arrangements to marriage who say that the institution is becoming obsolete. Some 42% of self-described conservatives (compared with 38% of liberals and 34% of moderates) say the same— even though conservatives are less likely than moderates or liberals to have ever cohabited. They are also the most likely of the three ideology groups to say that the growing variety in family arrangements is a bad thing.

It's no small thing when nearly four-in-ten (39%) Americans agree that the world's most enduring social institution is becoming obsolete. Nonetheless, this finding needs to be interpreted with caution.

For one thing, "becoming obsolete" is not the same as "obsolete." When the World Values Survey posed a similar question in 2006 that used a more starkly worded formulation ("Marriage is an outdated institution—agree or disagree?"), just 13% of American respondents agreed.

In addition, respondents who doubt the durability of marriage appear to include a mix of those who are comfortable with the change and those who are troubled by it.

Among the demographic groups most likely to agree that marriage is becoming obsolete are the young (44% of 18- to 29-year-olds say this), blacks (44%), those who have a high school diploma or less (45%) and those whose annual income is less than $30,000 (48%). All of these groups are less likely than their demographic opposites (older, white, college educated, higher income) to be married—and thus their judgments could well be shaped to some degree by their life experiences.

These differences come into sharper focus when one looks specifically at respondents' marital status. Just 31% of married adults agree that marriage is becoming obsolete, compared with 46% of all unmarried adults, 58% of all single parents and 62% of all cohabiting (but unmarried) parents.

But it's not just those who are living out alternative arrangements to marriage who say that the institution is becoming obsolete. Some 42% of self-described conservatives (compared with 38% of liberals and 34% of moderates) say the same— even though conservatives are less likely than moderates or liberals to have ever cohabited. They are also the most likely of the three ideology groups to say that the growing variety in family arrangements is a bad thing.

Gender Roles; Family Finances

About four-in-ten Americans think that marriage is on the rocks. No, not their marriage. The institution of marriage. In response to the question, "Some people say that the present institution of marriage is becoming obsolete—do you agree or disagree?" some 39% of survey respondents say they agree, while 58% disagree and 4% say they don't know.

As family historians[18. numoffset="16" See, for example, Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005. Pages 1-12.] have noted, observations about the fragility of marriage are as old and universal as marriage itself—meaning they've been around for thousands of years and permeated virtually every culture and corner of the globe.

Nevertheless, there's been a notable rise in recent decades in this country in the perception that marriage's best days are behind it. When this same question was posed on a 1978 survey, just 28% agreed with the premise.[19. This 1978 Time/Yankelovich, Skelly & White survey was among registered voters only. The “agree” response among registered voters in the 2010 survey was 36%.]

No matter what one thinks about the institution's future, there's no getting around its stark contraction during the past half century. Some 72% of all adults in the United States were married in 1960. By 2008, just 52% were.

Does this trend line lead inevitably to obsolescence? The notion that it does attracts some strange bedfellows—those who are contributing to the phenomenon (55% of cohabiters) as well as those who are most likely to be troubled by it (42% of self-described conservatives).

About four-in-ten Americans think that marriage is on the rocks. No, not their marriage. The institution of marriage. In response to the question, "Some people say that the present institution of marriage is becoming obsolete—do you agree or disagree?" some 39% of survey respondents say they agree, while 58% disagree and 4% say they don't know.

As family historians[18. numoffset="16" See, for example, Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005. Pages 1-12.] have noted, observations about the fragility of marriage are as old and universal as marriage itself—meaning they've been around for thousands of years and permeated virtually every culture and corner of the globe.

Nevertheless, there's been a notable rise in recent decades in this country in the perception that marriage's best days are behind it. When this same question was posed on a 1978 survey, just 28% agreed with the premise.[19. This 1978 Time/Yankelovich, Skelly & White survey was among registered voters only. The “agree” response among registered voters in the 2010 survey was 36%.]

No matter what one thinks about the institution's future, there's no getting around its stark contraction during the past half century. Some 72% of all adults in the United States were married in 1960. By 2008, just 52% were.

Does this trend line lead inevitably to obsolescence? The notion that it does attracts some strange bedfellows—those who are contributing to the phenomenon (55% of cohabiters) as well as those who are most likely to be troubled by it (42% of self-described conservatives).

The survey reveals other intriguing cross-currents in the public's attitudes about marriage. For example, most Americans now embrace the ideal of gender equality between spouses. The mid-20th century "Ozzie and Harriet" marriage between a breadwinner husband and a homemaker wife is now seen as the preferred model by just 30% of the public; some 62% say that marriages are better when husbands and wives both have jobs and both share responsibility for the household and kids.

The survey reveals other intriguing cross-currents in the public's attitudes about marriage. For example, most Americans now embrace the ideal of gender equality between spouses. The mid-20th century "Ozzie and Harriet" marriage between a breadwinner husband and a homemaker wife is now seen as the preferred model by just 30% of the public; some 62% say that marriages are better when husbands and wives both have jobs and both share responsibility for the household and kids.

Even as public opinion embraces the ideal of spousal equality, however, it still hasn't given up the seemingly contradictory notion that men—far more than women—need to be good providers in order to be good marriage prospects. Two-thirds of survey respondents say this about men, while just one-third say it about women.

But comes now another wrinkle. To hear the public tell it, financial security isn't all that important to marriage. Asked to evaluate the reasons they got married, married respondents place the greatest value on love (93% say this is a very important reason), followed by making a lifelong commitment (87%), companionship (81%), having children (59%), and, at the bottom of the list, financial stability (31%). Unmarried adults order the reasons the same way when asked to evaluate why they would consider getting married.

The potency of the link between love and marriage is relatively new in the sweep of human history—and, in the view of some historians, a leading cause of the institution's decline.[20. Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005.] For several millennia, economic security was the sine qua non of marriage. The institution thrived as an efficient way to divide labor, allocate resources, propagate the species and ensure that someone will take care of you when you get old. Only in recent centuries have love and mutual self-fulfillment come to occupy center stage in the grand marital bargain. But as the trends of the past half century attest, it's an open question whether a social institution built on love will prove as durable as one built on economic security.

Even as public opinion embraces the ideal of spousal equality, however, it still hasn't given up the seemingly contradictory notion that men—far more than women—need to be good providers in order to be good marriage prospects. Two-thirds of survey respondents say this about men, while just one-third say it about women.

But comes now another wrinkle. To hear the public tell it, financial security isn't all that important to marriage. Asked to evaluate the reasons they got married, married respondents place the greatest value on love (93% say this is a very important reason), followed by making a lifelong commitment (87%), companionship (81%), having children (59%), and, at the bottom of the list, financial stability (31%). Unmarried adults order the reasons the same way when asked to evaluate why they would consider getting married.

The potency of the link between love and marriage is relatively new in the sweep of human history—and, in the view of some historians, a leading cause of the institution's decline.[20. Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005.] For several millennia, economic security was the sine qua non of marriage. The institution thrived as an efficient way to divide labor, allocate resources, propagate the species and ensure that someone will take care of you when you get old. Only in recent centuries have love and mutual self-fulfillment come to occupy center stage in the grand marital bargain. But as the trends of the past half century attest, it's an open question whether a social institution built on love will prove as durable as one built on economic security.

Less Money, Less Marriage

If economic security is no longer a key reason people marry, the lack of economic security nonetheless appears to be a key reason people don't get married. As noted in the overview of this report, 50 years ago there was virtually no difference by socio-economic status in the proclivity to marry: 76% of college graduates and 72% of adults who did not attend college were married in 1960. By 2008, that small gap had widened to a chasm: 64% of college graduates were married, compared with just 48% of those with a high school diploma or less. During this same period, the income gap between the well-educated and the less-educated—and between the rich and poor—also widened substantially.[21. See for instance “Changes in Income Inequality across the U.S.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Sep 21, 2007.]

The 2010 Pew Research survey finds that among the unmarried, there are no significant differences by education or income in the desire to get married; just under half of the college educated (46%) and those who have a high school diploma or less (44%) would like to get married. Likewise, roughly similar shares of the unmarried who earn above and below $100,000 a year would like to marry.

But the survey also finds that the less education and income people have, the more likely they are to say that in order to be a good marriage prospect, a person must be able to support a family financially. Taken together, these findings suggest that those with less income and education are opting out of marriage not because they don't value the institution or aspire to it benefits, but because they may doubt that they (or a potential spouse) can meet the standards they impose on marriage.

The Upsides of Marriage

Not all of the survey findings are harbingers of gloom and doom for the institution of marriage. Even among those who are not currently married, getting hitched continues to have appeal. A plurality of 46% of those who are not married say they would like to marry, while three-in-ten (29%) say they are not sure. Just one-in-four say they don't want to marry.

Not all of the survey findings are harbingers of gloom and doom for the institution of marriage. Even among those who are not currently married, getting hitched continues to have appeal. A plurality of 46% of those who are not married say they would like to marry, while three-in-ten (29%) say they are not sure. Just one-in-four say they don't want to marry.

Moreover, marriage may have been more prevalent a generation ago, but most married or cohabiting respondents today believe their own relationship compares favorably with their parents'. Some 51% say they have a closer relationship with their spouse or partner than their parents had with each other, while just 5% characterize their own relationship as less close. The remainder—43%—say there is no difference.

A majority of adults believe that in many key realms of life—such as finding happiness, getting ahead in a career or having social status—it doesn't make any difference whether a person is married or single. However, among those who believe it does make a difference, most say that being married is better.

For example, when it comes to being financially secure, 35% of respondents believe this is easier to do as a married person, while 11% say it is easier for a single person and half say it makes no difference. Similar patterns emerge for having a fulfilling sexual life, finding happiness and having social status. The two outliers from this pattern are raising a family (fully 77% say this is easier for a married person) and getting ahead in a career (just 14% say this is easier for a married person, compared with 24% who say it is easier for a single person).

Finally, a classic question about love was posed in the survey: Do you agree or disagree that there is only one true love for each person? Nearly three-in-ten (28%) Americans agree, while 69% disagree. Among the minority who believe in just one true love, 79% say—in response to a follow-up question—that they've found theirs. And among those in this group who are married, 96% say they've found theirs—meaning that virtually all are either deeply committed or very careful with their words.

The remainder of this chapter examines all of these questions in depth and explores the demographic patterns in attitudes and behaviors related to marriage.

Moreover, marriage may have been more prevalent a generation ago, but most married or cohabiting respondents today believe their own relationship compares favorably with their parents'. Some 51% say they have a closer relationship with their spouse or partner than their parents had with each other, while just 5% characterize their own relationship as less close. The remainder—43%—say there is no difference.

A majority of adults believe that in many key realms of life—such as finding happiness, getting ahead in a career or having social status—it doesn't make any difference whether a person is married or single. However, among those who believe it does make a difference, most say that being married is better.

For example, when it comes to being financially secure, 35% of respondents believe this is easier to do as a married person, while 11% say it is easier for a single person and half say it makes no difference. Similar patterns emerge for having a fulfilling sexual life, finding happiness and having social status. The two outliers from this pattern are raising a family (fully 77% say this is easier for a married person) and getting ahead in a career (just 14% say this is easier for a married person, compared with 24% who say it is easier for a single person).

Finally, a classic question about love was posed in the survey: Do you agree or disagree that there is only one true love for each person? Nearly three-in-ten (28%) Americans agree, while 69% disagree. Among the minority who believe in just one true love, 79% say—in response to a follow-up question—that they've found theirs. And among those in this group who are married, 96% say they've found theirs—meaning that virtually all are either deeply committed or very careful with their words.

The remainder of this chapter examines all of these questions in depth and explores the demographic patterns in attitudes and behaviors related to marriage.

Is Marriage Becoming Obsolete?

It's no small thing when nearly four-in-ten (39%) Americans agree that the world's most enduring social institution is becoming obsolete. Nonetheless, this finding needs to be interpreted with caution.

For one thing, "becoming obsolete" is not the same as "obsolete." When the World Values Survey posed a similar question in 2006 that used a more starkly worded formulation ("Marriage is an outdated institution—agree or disagree?"), just 13% of American respondents agreed.

In addition, respondents who doubt the durability of marriage appear to include a mix of those who are comfortable with the change and those who are troubled by it.

Among the demographic groups most likely to agree that marriage is becoming obsolete are the young (44% of 18- to 29-year-olds say this), blacks (44%), those who have a high school diploma or less (45%) and those whose annual income is less than $30,000 (48%). All of these groups are less likely than their demographic opposites (older, white, college educated, higher income) to be married—and thus their judgments could well be shaped to some degree by their life experiences.

These differences come into sharper focus when one looks specifically at respondents' marital status. Just 31% of married adults agree that marriage is becoming obsolete, compared with 46% of all unmarried adults, 58% of all single parents and 62% of all cohabiting (but unmarried) parents.

But it's not just those who are living out alternative arrangements to marriage who say that the institution is becoming obsolete. Some 42% of self-described conservatives (compared with 38% of liberals and 34% of moderates) say the same— even though conservatives are less likely than moderates or liberals to have ever cohabited. They are also the most likely of the three ideology groups to say that the growing variety in family arrangements is a bad thing.

It's no small thing when nearly four-in-ten (39%) Americans agree that the world's most enduring social institution is becoming obsolete. Nonetheless, this finding needs to be interpreted with caution.

For one thing, "becoming obsolete" is not the same as "obsolete." When the World Values Survey posed a similar question in 2006 that used a more starkly worded formulation ("Marriage is an outdated institution—agree or disagree?"), just 13% of American respondents agreed.

In addition, respondents who doubt the durability of marriage appear to include a mix of those who are comfortable with the change and those who are troubled by it.

Among the demographic groups most likely to agree that marriage is becoming obsolete are the young (44% of 18- to 29-year-olds say this), blacks (44%), those who have a high school diploma or less (45%) and those whose annual income is less than $30,000 (48%). All of these groups are less likely than their demographic opposites (older, white, college educated, higher income) to be married—and thus their judgments could well be shaped to some degree by their life experiences.

These differences come into sharper focus when one looks specifically at respondents' marital status. Just 31% of married adults agree that marriage is becoming obsolete, compared with 46% of all unmarried adults, 58% of all single parents and 62% of all cohabiting (but unmarried) parents.

But it's not just those who are living out alternative arrangements to marriage who say that the institution is becoming obsolete. Some 42% of self-described conservatives (compared with 38% of liberals and 34% of moderates) say the same— even though conservatives are less likely than moderates or liberals to have ever cohabited. They are also the most likely of the three ideology groups to say that the growing variety in family arrangements is a bad thing.

Gender Roles; Family Finances

When it comes to attitudes about how spouses should divide responsibilities, social norms have changed. Back in 1977, survey respondents were nearly equally divided between those who said marriages are more satisfying when the husband earns an income and the wife takes care of the household and children (43%) and those who said marriages work best when both spouses have jobs and both take care of the household and children (48%).

By 2010, public opinion shifted heavily in favor of the dual income/shared homemaker model, with survey respondents favoring this template by 62% to 30% over the arrangement that was much more prevalent half a century ago.

When it comes to attitudes about how spouses should divide responsibilities, social norms have changed. Back in 1977, survey respondents were nearly equally divided between those who said marriages are more satisfying when the husband earns an income and the wife takes care of the household and children (43%) and those who said marriages work best when both spouses have jobs and both take care of the household and children (48%).

By 2010, public opinion shifted heavily in favor of the dual income/shared homemaker model, with survey respondents favoring this template by 62% to 30% over the arrangement that was much more prevalent half a century ago.

No major subgroup of survey respondents favors the older model, but some are more disposed that way than others. For example, 42% of self-described conservatives, 42% of Republicans and 37% of adults ages 65 and older say the traditional arrangement will lead to more satisfying lives.

Also, slightly more men (33%) than women (26%) feel this way. And the married (35%) are more inclined than the unmarried (24%) to say this.

Despite the public's strong preference for the two-earner/shared homemaker marriage, the public hasn't fully abandoned the idea that men and women play different roles in a marriage. Indeed, when it comes to evaluating the earning power of future mates, the public still has one standard for prospective husbands and a different one for future wives.

Asked how important it is for a man to be able to support a family financially if he wants to get married, fully 67% of the public say it is "very important." But when the same question is asked about a woman, just 33% say it is very important.

There are some differences by gender in these responses, but they do not alter the basic pattern. Among male respondents, 70% say a man who is about to marry must be able to support a family, while just 27% say the same about a woman. Among female respondents, 64% say that about a man and 39% about a woman.

No major subgroup of survey respondents favors the older model, but some are more disposed that way than others. For example, 42% of self-described conservatives, 42% of Republicans and 37% of adults ages 65 and older say the traditional arrangement will lead to more satisfying lives.

Also, slightly more men (33%) than women (26%) feel this way. And the married (35%) are more inclined than the unmarried (24%) to say this.

Despite the public's strong preference for the two-earner/shared homemaker marriage, the public hasn't fully abandoned the idea that men and women play different roles in a marriage. Indeed, when it comes to evaluating the earning power of future mates, the public still has one standard for prospective husbands and a different one for future wives.

Asked how important it is for a man to be able to support a family financially if he wants to get married, fully 67% of the public say it is "very important." But when the same question is asked about a woman, just 33% say it is very important.

There are some differences by gender in these responses, but they do not alter the basic pattern. Among male respondents, 70% say a man who is about to marry must be able to support a family, while just 27% say the same about a woman. Among female respondents, 64% say that about a man and 39% about a woman.

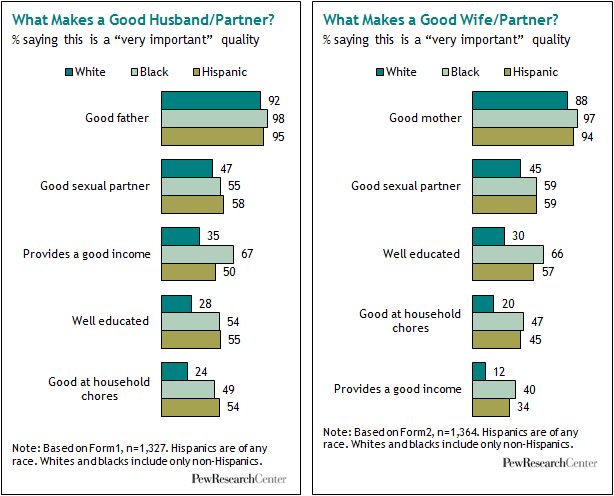

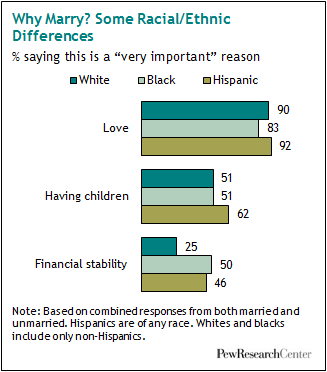

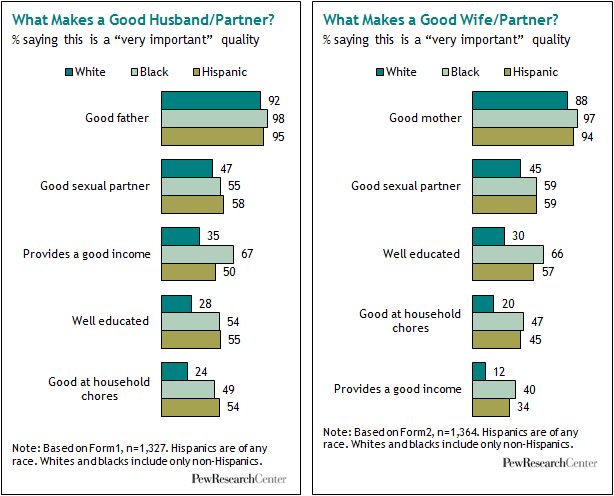

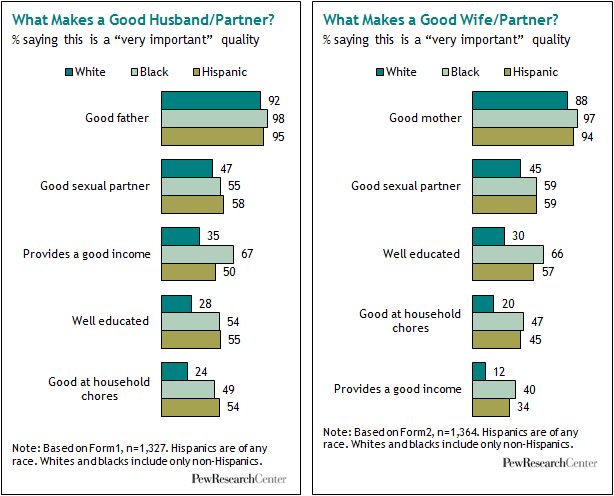

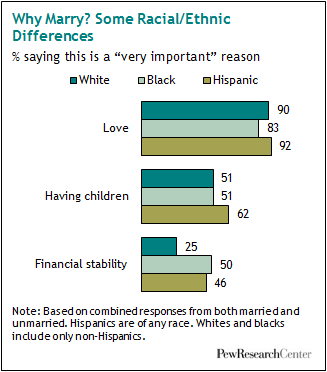

Race and Marriage

About four-in-ten Americans think that marriage is on the rocks. No, not their marriage. The institution of marriage. In response to the question, "Some people say that the present institution of marriage is becoming obsolete—do you agree or disagree?" some 39% of survey respondents say they agree, while 58% disagree and 4% say they don't know.

As family historians[18. numoffset="16" See, for example, Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005. Pages 1-12.] have noted, observations about the fragility of marriage are as old and universal as marriage itself—meaning they've been around for thousands of years and permeated virtually every culture and corner of the globe.

Nevertheless, there's been a notable rise in recent decades in this country in the perception that marriage's best days are behind it. When this same question was posed on a 1978 survey, just 28% agreed with the premise.[19. This 1978 Time/Yankelovich, Skelly & White survey was among registered voters only. The “agree” response among registered voters in the 2010 survey was 36%.]

No matter what one thinks about the institution's future, there's no getting around its stark contraction during the past half century. Some 72% of all adults in the United States were married in 1960. By 2008, just 52% were.

Does this trend line lead inevitably to obsolescence? The notion that it does attracts some strange bedfellows—those who are contributing to the phenomenon (55% of cohabiters) as well as those who are most likely to be troubled by it (42% of self-described conservatives).

About four-in-ten Americans think that marriage is on the rocks. No, not their marriage. The institution of marriage. In response to the question, "Some people say that the present institution of marriage is becoming obsolete—do you agree or disagree?" some 39% of survey respondents say they agree, while 58% disagree and 4% say they don't know.

As family historians[18. numoffset="16" See, for example, Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005. Pages 1-12.] have noted, observations about the fragility of marriage are as old and universal as marriage itself—meaning they've been around for thousands of years and permeated virtually every culture and corner of the globe.

Nevertheless, there's been a notable rise in recent decades in this country in the perception that marriage's best days are behind it. When this same question was posed on a 1978 survey, just 28% agreed with the premise.[19. This 1978 Time/Yankelovich, Skelly & White survey was among registered voters only. The “agree” response among registered voters in the 2010 survey was 36%.]

No matter what one thinks about the institution's future, there's no getting around its stark contraction during the past half century. Some 72% of all adults in the United States were married in 1960. By 2008, just 52% were.

Does this trend line lead inevitably to obsolescence? The notion that it does attracts some strange bedfellows—those who are contributing to the phenomenon (55% of cohabiters) as well as those who are most likely to be troubled by it (42% of self-described conservatives).

The survey reveals other intriguing cross-currents in the public's attitudes about marriage. For example, most Americans now embrace the ideal of gender equality between spouses. The mid-20th century "Ozzie and Harriet" marriage between a breadwinner husband and a homemaker wife is now seen as the preferred model by just 30% of the public; some 62% say that marriages are better when husbands and wives both have jobs and both share responsibility for the household and kids.

The survey reveals other intriguing cross-currents in the public's attitudes about marriage. For example, most Americans now embrace the ideal of gender equality between spouses. The mid-20th century "Ozzie and Harriet" marriage between a breadwinner husband and a homemaker wife is now seen as the preferred model by just 30% of the public; some 62% say that marriages are better when husbands and wives both have jobs and both share responsibility for the household and kids.

Even as public opinion embraces the ideal of spousal equality, however, it still hasn't given up the seemingly contradictory notion that men—far more than women—need to be good providers in order to be good marriage prospects. Two-thirds of survey respondents say this about men, while just one-third say it about women.

But comes now another wrinkle. To hear the public tell it, financial security isn't all that important to marriage. Asked to evaluate the reasons they got married, married respondents place the greatest value on love (93% say this is a very important reason), followed by making a lifelong commitment (87%), companionship (81%), having children (59%), and, at the bottom of the list, financial stability (31%). Unmarried adults order the reasons the same way when asked to evaluate why they would consider getting married.

The potency of the link between love and marriage is relatively new in the sweep of human history—and, in the view of some historians, a leading cause of the institution's decline.[20. Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005.] For several millennia, economic security was the sine qua non of marriage. The institution thrived as an efficient way to divide labor, allocate resources, propagate the species and ensure that someone will take care of you when you get old. Only in recent centuries have love and mutual self-fulfillment come to occupy center stage in the grand marital bargain. But as the trends of the past half century attest, it's an open question whether a social institution built on love will prove as durable as one built on economic security.

Even as public opinion embraces the ideal of spousal equality, however, it still hasn't given up the seemingly contradictory notion that men—far more than women—need to be good providers in order to be good marriage prospects. Two-thirds of survey respondents say this about men, while just one-third say it about women.

But comes now another wrinkle. To hear the public tell it, financial security isn't all that important to marriage. Asked to evaluate the reasons they got married, married respondents place the greatest value on love (93% say this is a very important reason), followed by making a lifelong commitment (87%), companionship (81%), having children (59%), and, at the bottom of the list, financial stability (31%). Unmarried adults order the reasons the same way when asked to evaluate why they would consider getting married.

The potency of the link between love and marriage is relatively new in the sweep of human history—and, in the view of some historians, a leading cause of the institution's decline.[20. Coontz, Stephanie, Marriage, a History, Penguin Books, 2005.] For several millennia, economic security was the sine qua non of marriage. The institution thrived as an efficient way to divide labor, allocate resources, propagate the species and ensure that someone will take care of you when you get old. Only in recent centuries have love and mutual self-fulfillment come to occupy center stage in the grand marital bargain. But as the trends of the past half century attest, it's an open question whether a social institution built on love will prove as durable as one built on economic security.

Less Money, Less Marriage

If economic security is no longer a key reason people marry, the lack of economic security nonetheless appears to be a key reason people don't get married. As noted in the overview of this report, 50 years ago there was virtually no difference by socio-economic status in the proclivity to marry: 76% of college graduates and 72% of adults who did not attend college were married in 1960. By 2008, that small gap had widened to a chasm: 64% of college graduates were married, compared with just 48% of those with a high school diploma or less. During this same period, the income gap between the well-educated and the less-educated—and between the rich and poor—also widened substantially.[21. See for instance “Changes in Income Inequality across the U.S.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Sep 21, 2007.]

The 2010 Pew Research survey finds that among the unmarried, there are no significant differences by education or income in the desire to get married; just under half of the college educated (46%) and those who have a high school diploma or less (44%) would like to get married. Likewise, roughly similar shares of the unmarried who earn above and below $100,000 a year would like to marry.

But the survey also finds that the less education and income people have, the more likely they are to say that in order to be a good marriage prospect, a person must be able to support a family financially. Taken together, these findings suggest that those with less income and education are opting out of marriage not because they don't value the institution or aspire to it benefits, but because they may doubt that they (or a potential spouse) can meet the standards they impose on marriage.

The Upsides of Marriage

Not all of the survey findings are harbingers of gloom and doom for the institution of marriage. Even among those who are not currently married, getting hitched continues to have appeal. A plurality of 46% of those who are not married say they would like to marry, while three-in-ten (29%) say they are not sure. Just one-in-four say they don't want to marry.

Not all of the survey findings are harbingers of gloom and doom for the institution of marriage. Even among those who are not currently married, getting hitched continues to have appeal. A plurality of 46% of those who are not married say they would like to marry, while three-in-ten (29%) say they are not sure. Just one-in-four say they don't want to marry.

Moreover, marriage may have been more prevalent a generation ago, but most married or cohabiting respondents today believe their own relationship compares favorably with their parents'. Some 51% say they have a closer relationship with their spouse or partner than their parents had with each other, while just 5% characterize their own relationship as less close. The remainder—43%—say there is no difference.

A majority of adults believe that in many key realms of life—such as finding happiness, getting ahead in a career or having social status—it doesn't make any difference whether a person is married or single. However, among those who believe it does make a difference, most say that being married is better.

For example, when it comes to being financially secure, 35% of respondents believe this is easier to do as a married person, while 11% say it is easier for a single person and half say it makes no difference. Similar patterns emerge for having a fulfilling sexual life, finding happiness and having social status. The two outliers from this pattern are raising a family (fully 77% say this is easier for a married person) and getting ahead in a career (just 14% say this is easier for a married person, compared with 24% who say it is easier for a single person).

Finally, a classic question about love was posed in the survey: Do you agree or disagree that there is only one true love for each person? Nearly three-in-ten (28%) Americans agree, while 69% disagree. Among the minority who believe in just one true love, 79% say—in response to a follow-up question—that they've found theirs. And among those in this group who are married, 96% say they've found theirs—meaning that virtually all are either deeply committed or very careful with their words.

The remainder of this chapter examines all of these questions in depth and explores the demographic patterns in attitudes and behaviors related to marriage.

Moreover, marriage may have been more prevalent a generation ago, but most married or cohabiting respondents today believe their own relationship compares favorably with their parents'. Some 51% say they have a closer relationship with their spouse or partner than their parents had with each other, while just 5% characterize their own relationship as less close. The remainder—43%—say there is no difference.

A majority of adults believe that in many key realms of life—such as finding happiness, getting ahead in a career or having social status—it doesn't make any difference whether a person is married or single. However, among those who believe it does make a difference, most say that being married is better.

For example, when it comes to being financially secure, 35% of respondents believe this is easier to do as a married person, while 11% say it is easier for a single person and half say it makes no difference. Similar patterns emerge for having a fulfilling sexual life, finding happiness and having social status. The two outliers from this pattern are raising a family (fully 77% say this is easier for a married person) and getting ahead in a career (just 14% say this is easier for a married person, compared with 24% who say it is easier for a single person).