What it means to be a military veteran in the United States is being shaped by a new generation of service members. About one-in-five veterans today served on active duty after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Their collective experiences – from deployment to combat to the transition back to civilian life – are markedly different from those who served in previous eras.

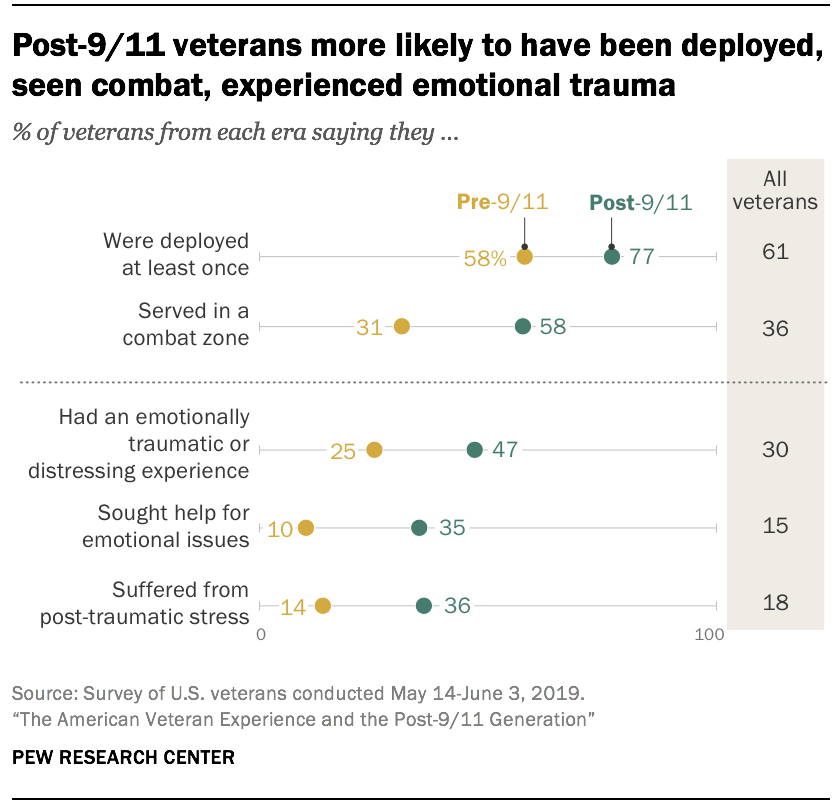

Roughly three-quarters of post-9/11 veterans were deployed at least once, compared with 58% of those who served before them. And post-9/11 veterans are about twice as likely as their pre-9/11 counterparts to have served in a combat zone.

Roughly three-quarters of post-9/11 veterans were deployed at least once, compared with 58% of those who served before them. And post-9/11 veterans are about twice as likely as their pre-9/11 counterparts to have served in a combat zone.

Because they are more likely to have been deployed and to have seen combat, post-9/11 veterans are also more likely to bear the scars of battle, whether physical or not. Roughly half say they had emotionally traumatic or distressing experiences related to their military service, and about a third say they sought professional help to deal with those experiences. In addition, 36% say that – regardless of whether they have sought help – they think they have suffered from post-traumatic stress (PTS), according to a new Pew Research Center survey of U.S. military veterans.1

How we defined veterans

In thinking about their service, a majority of all veterans express pride. Still, those who served in the post-9/11 era are somewhat less likely than their predecessors to say they frequently felt proud after leaving the military (58% vs. 70%).

For many veterans, the imprint of war is felt beyond their tour of duty and carries over into the transition from military to civilian life. This is true regardless of era of service. When asked about their experiences in the first few years after leaving the military, combat veterans are less likely than those who didn’t serve in combat to say they frequently felt optimistic about their future, and they are more likely to say they didn’t get the respect they deserved, struggled with the lack of structure in civilian life, and felt disconnected from family or friends.

At the same time, those who served in combat report positive impacts from the experience. Majorities say their experiences in combat made them feel closer to those who served alongside them, showed them that they were stronger than they thought they were and changed their priorities about what was important in their life.

Most veterans say their training prepared them for military life fewer say the military prepared them for what came next

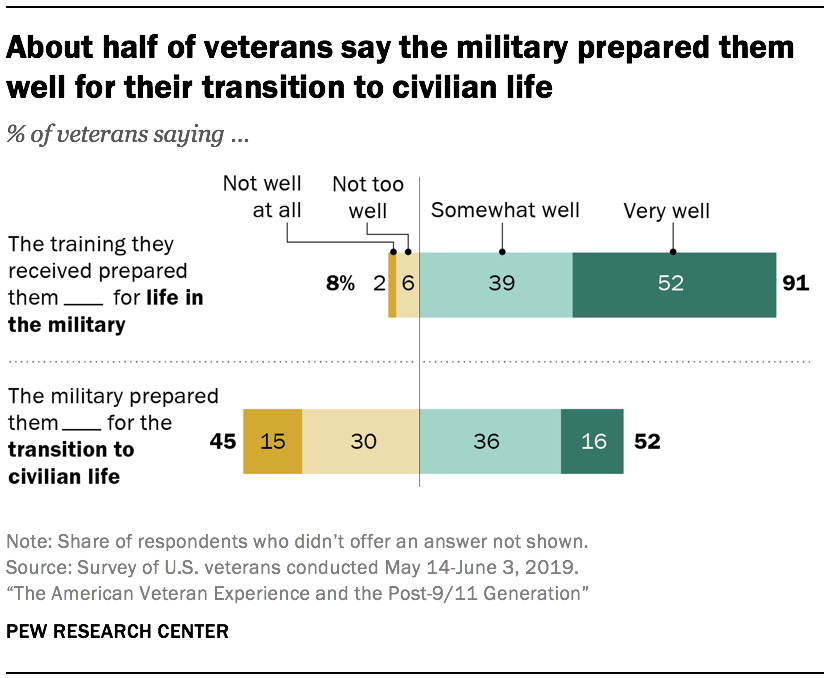

Veterans give the military high marks for preparing them to serve. Roughly nine-in-ten say the training they received when they first entered the military prepared them very or somewhat well for military life. Post-9/11 and pre-9/11 veterans offer similarly positive assessments of their training and readiness.

Veterans give the military high marks for preparing them to serve. Roughly nine-in-ten say the training they received when they first entered the military prepared them very or somewhat well for military life. Post-9/11 and pre-9/11 veterans offer similarly positive assessments of their training and readiness.

However, they are less affirmative about the job the military did preparing them for the transition to civilian life. About half of all veterans say the military prepared them very or somewhat well; a similar share says the military didn’t prepare them too well or at all.

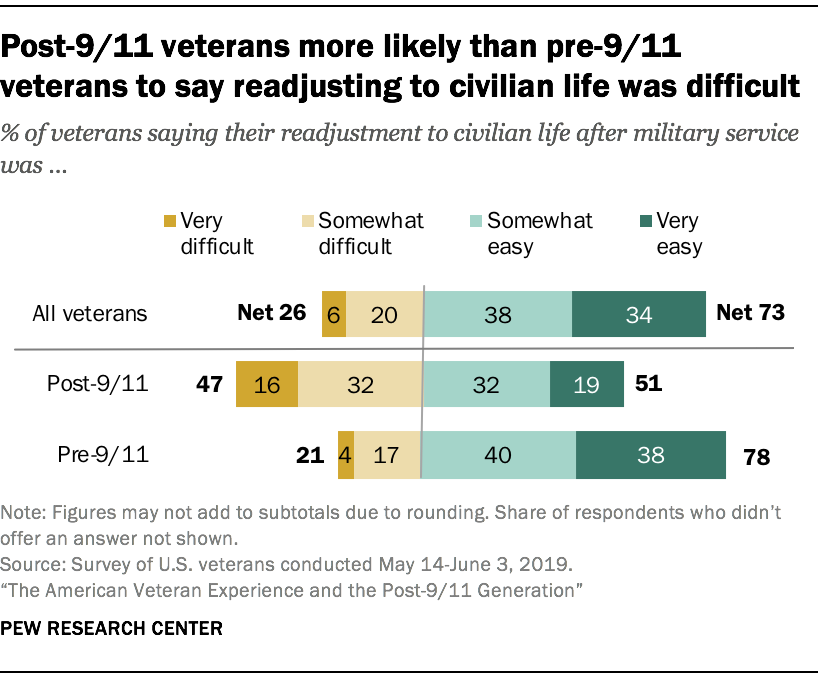

While veterans across eras offer similar evaluations of the job the military did preparing them for civilian life, post-9/11 veterans are much more likely than those who served before them to say their readjustment to civilian life was difficult. About half of post-9/11 veterans say it was somewhat or very difficult for them to readjust to civilian life after their military service; only about one-in-five pre-9/11 veterans say the same. Combat veterans are especially likely to say they struggled with the transition, and this is particularly true of those who had emotionally traumatic experiences.

While veterans across eras offer similar evaluations of the job the military did preparing them for civilian life, post-9/11 veterans are much more likely than those who served before them to say their readjustment to civilian life was difficult. About half of post-9/11 veterans say it was somewhat or very difficult for them to readjust to civilian life after their military service; only about one-in-five pre-9/11 veterans say the same. Combat veterans are especially likely to say they struggled with the transition, and this is particularly true of those who had emotionally traumatic experiences.

The challenges some veterans face during the transition can be financial, emotional and professional. About a third of veterans say they had trouble paying their bills in their first few years after leaving the military, and roughly three-in-ten say they received unemployment compensation. One-in-five say they struggled with alcohol or substance abuse. Veterans who had emotionally traumatic experiences related to their military service are more likely than those who did not to report experiencing these things.

When it comes to employment specifically, a majority of veterans say their military service was useful in giving them the skills and training they needed for a job outside the military. Veterans who served as commissioned officers in the military are significantly more likely than those who served as noncommissioned officers or enlisted personnel to say their military training was good preparation for a civilian job.

For most post-9/11 veterans, having served in the military was an advantage when it came to finding their first post-military job – 35% say this helped a lot and 26% say it helped a little. Only about one-in-ten say having served in the military hurt their ability to get a job.

Veterans, public say most Americans look up to people who served in the military; majorities associate discipline and patriotism with veterans

Veterans view themselves as distinct from other Americans in some ways but not in others. Majorities among veterans (61%) and the general public (64%) say most Americans look up to people who have served in the military. Only about one-in-ten veterans (9%) and an even smaller share of all adults say most Americans look down on people who have served. Three-in-ten from each group say most Americans neither look up to nor down on veterans.

Majorities of the public across gender, age groups and political parties say veterans are generally looked up to by most Americans. Among veterans, this sentiment is echoed across eras of service.

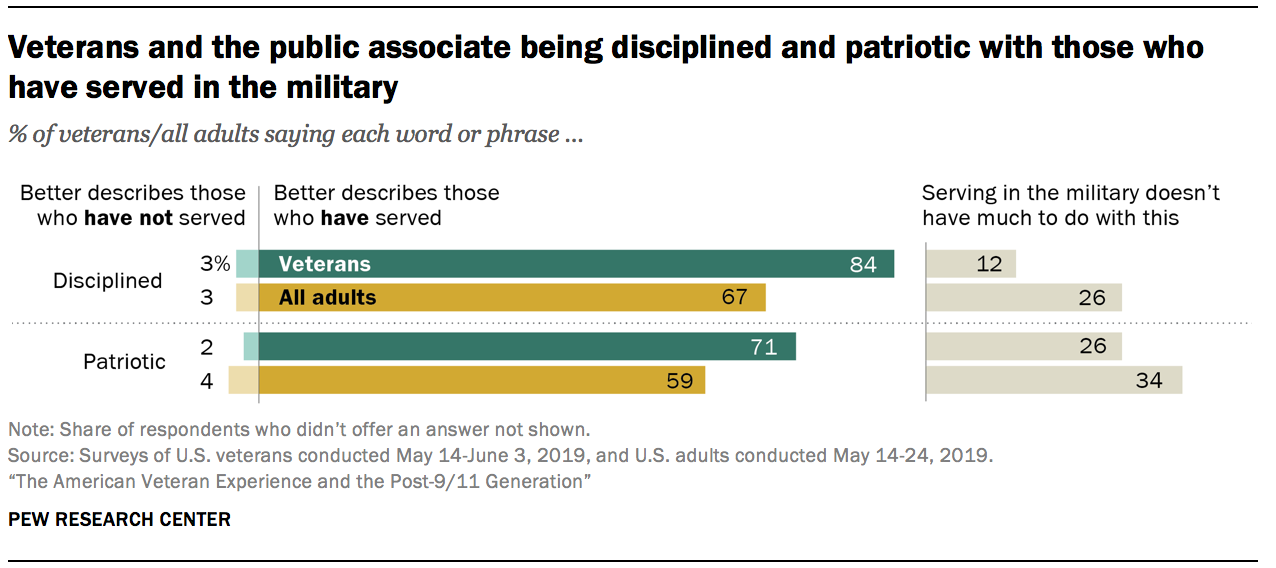

Veterans overwhelmingly see themselves as more disciplined than those who have not served in the military. Some 84% of all veterans say this characteristic better describes those who have served in the military than those who have not. Most Americans (67%) agree with this assessment. About one-in-four among the public (26%) say being disciplined doesn’t have much to do with whether one served in the military or not.

Similarly, a large majority of veterans (71%) say the term patriotic better describes those who served in the military than those who did not; 59% of the pubic shares this view. About a third of Americans say patriotism isn’t related to whether one is a veteran or not.

Veterans and the public are less likely to associate certain negative traits with those who have served in the military. Some 13% of veterans and 25% of the public say being emotionally unstable better describes those who have served in the military than those who have not. Most in each group say this doesn’t have much to do with having been in the military. The pattern is similar when it comes to being prone to violence.

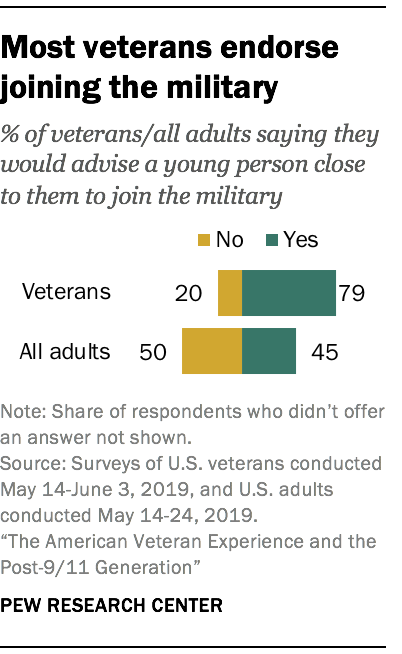

A large majority of veterans endorse the military as a career choice. Roughly eight-in-ten say they would advise a young person close to them to join the military. This includes large majorities of post-9/11 veterans, combat veterans and those who say they had emotionally traumatic experiences in the military. The public is more evenly divided about this: 45% of all American adults say they would advise a young person close to them to join the military, 50% say they would not. In addition, veterans and the public have differing views on the current administration and its leadership of the military.

A large majority of veterans endorse the military as a career choice. Roughly eight-in-ten say they would advise a young person close to them to join the military. This includes large majorities of post-9/11 veterans, combat veterans and those who say they had emotionally traumatic experiences in the military. The public is more evenly divided about this: 45% of all American adults say they would advise a young person close to them to join the military, 50% say they would not. In addition, veterans and the public have differing views on the current administration and its leadership of the military.

These findings are based on two surveys: one of 1,284 U.S. military veterans (including 797 veterans who only served prior to September 11, 2001 and 487 “post-9/11 veterans” who served any time after 9/11), conducted online May 14-June 3, 2019, and a parallel survey of 1,087 U.S. adults, conducted May 14-24, 2019.

Other key findings:

Deployment and combat

- Among veterans who were deployed at least once, post-9/11 veterans are much more likely than pre-9/11 veterans to report certain positive and negative consequences from deployment. Two-thirds of post-9/11 veterans say being deployed had a positive impact on their financial situation (compared with 30% of pre-9/11 veterans). At the same time, 42% of post-9/11 veterans – but only 17% of pre-9/11 veterans – say being deployed had a negative impact on their mental health.

- About a third of veterans (35%) say they knew and served with someone who was seriously injured in combat while performing their duties; 30% knew and served with someone who was killed in combat. Among combat veterans, 57% say they personally witnessed someone from their unit or an ally unit being seriously wounded or killed.

- Veterans who say they have suffered from PTS are much more likely than those who have not to report certain negative experiences in the first few years after they left the military. Roughly six-in-ten (61%) say they had trouble paying their bills, about four-in-ten (42%) say they had trouble getting medical care for themselves or their families, and a similar share (41%) say they struggled with alcohol or substance abuse.

Government assistance

- A majority of veterans (64%) say the government has given them, as veterans, about as much help as it should have; 30% say the government has given them too little help. Post-9/11 veterans are more likely than those from previous eras to say the government has given them less help than it should have (43% vs. 27%).

- Most veterans (73%) say they have received benefits from the Department of Veterans Affairs. When asked to assess the job the VA is doing meeting the needs of veterans, fewer than half (46%) of all veterans say the VA is doing an excellent or good job in this regard.

Post-military employment

- One-in-four veterans say they had a job lined up when they left the military. Roughly half (48%) say they looked for a job right away, 21% say they looked for a job, but not right away, and 5% say they didn’t look for a job after leaving the military. Among those who looked for a job, 57% had one in less than six months.

- About half of veterans say they enrolled in school after leaving the military. Post-9/11 veterans are more likely than others to say they enrolled full-time – 36% vs. 24% of those who served in previous eras.

- A significant share of post-9/11 veterans (42%) who worked in a civilian job after leaving the military say they believe, based on their experience skills and training, they were overqualified for their first post-military job; 56% say they stayed in their first job for more than a year.