Twenty-five years after the release of the bestseller “Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus,” the debate over how and why men and women are different and what that means for their roles in society is far from settled. A new Pew Research Center survey finds that majorities of Americans say men and women are basically different in the way they express their feelings, their physical abilities, their personal interests and their approach to parenting. But there is no public consensus on the origins of these differences. While women who perceive differences generally attribute them to societal expectations, men tend to point to biological differences.

Twenty-five years after the release of the bestseller “Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus,” the debate over how and why men and women are different and what that means for their roles in society is far from settled. A new Pew Research Center survey finds that majorities of Americans say men and women are basically different in the way they express their feelings, their physical abilities, their personal interests and their approach to parenting. But there is no public consensus on the origins of these differences. While women who perceive differences generally attribute them to societal expectations, men tend to point to biological differences.

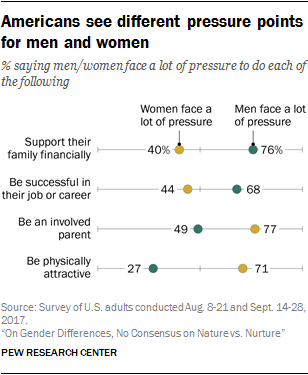

The public also sees vastly different pressure points for men and women as they navigate their roles in society. Large majorities say men face a lot of pressure to support their family financially (76%) and to be successful in their job or career (68%); much smaller shares say women face similar pressure in these areas. At the same time, seven-in-ten or more say women face a lot of pressure to be an involved parent (77%) and be physically attractive (71%). Far fewer say men face these types of pressures, and this is particularly the case when it comes to feeling pressure to be physically attractive: Only 27% say men face a lot of pressure in this regard.

The public also sees vastly different pressure points for men and women as they navigate their roles in society. Large majorities say men face a lot of pressure to support their family financially (76%) and to be successful in their job or career (68%); much smaller shares say women face similar pressure in these areas. At the same time, seven-in-ten or more say women face a lot of pressure to be an involved parent (77%) and be physically attractive (71%). Far fewer say men face these types of pressures, and this is particularly the case when it comes to feeling pressure to be physically attractive: Only 27% say men face a lot of pressure in this regard.

When asked in an open-ended question what traits society values most in men and women, the differences were also striking. The top responses about women related to physical attractiveness (35%) or nurturing and empathy (30%). For men, one-third pointed to honesty and morality, while about one-in-five mentioned professional or financial success (23%), ambition or leadership (19%), strength or toughness (19%) and a good work ethic (18%). Far fewer cite these as examples of what society values most in women.

The survey also finds a sense among the public that society places a higher premium on masculinity than it does on femininity. About half (53%) say most people in our society these days look up to men who are manly or masculine; far fewer (32%) say society looks up to feminine women. Yet, women are more likely to say it’s important to them to be seen by others as womanly or feminine than men are to say they want others to see them as manly or masculine.

Prior to conducting the survey, Pew Research Center conducted a qualitative test with nearly 200 men who were asked to list some traits and characteristics that come to mind when they think of a man who is manly or masculine and nearly 200 women who were asked what comes to mind when they think of a woman who is womanly or feminine. While these terms can have different meanings for different people, the qualitative testing revealed that respondents tended to associate “manly or masculine” with a common set of descriptions that relate to strength, confidence and certain physical traits. Some commonly used words included “strong,” “assertive,” “muscular,” “confident,” “deep voice” and “facial hair.” When it comes to traits and characteristics used to describe women who are “womanly or feminine,” some frequently used terms included “grace” or “graceful,” “beauty” or “beautiful,” “caring,” and “nurturing.” Many people also mentioned wearing makeup and dresses.

There are key demographic and political fault lines that cut across some of these views. Just as Republicans and Democrats are divided in their views on gender equality, they have divergent opinions about why men and women are different on various dimensions. Attitudes on gender issues also often differ by education, race and generation.

The nationally representative survey of 4,573 adults was conducted online Aug. 8-21 and Sept. 14-28, 2017, using Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel.1 Among the key findings:

Americans are divided along gender and party lines over whether differences between men and women are rooted in biology or societal expectations

Women and men who see gender differences in some key areas tend to have divergent views of the roles biology and society play in shaping these differences. Most women who see gender differences in the way people express their feelings, excel at work and approach parenting say those differences are mostly based on societal expectations. Men who see differences in these areas tend to believe biology is the driver.

Women and men who see gender differences in some key areas tend to have divergent views of the roles biology and society play in shaping these differences. Most women who see gender differences in the way people express their feelings, excel at work and approach parenting say those differences are mostly based on societal expectations. Men who see differences in these areas tend to believe biology is the driver.

Similarly, Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are far more likely than Republicans and those who lean to the GOP to say gender differences are mostly based on societal expectations rather than on biological differences between men and women. About two-thirds of Democrats who say men and women are basically different in how they express their feelings, their approach to parenting, and their hobbies and personal interests say these differences are rooted in societal expectations. Among their Republican counterparts, about four-in-ten or fewer share those views.

The public sees similarities between men and women in the workplace

While majorities of Americans see gender differences across various realms, one area where they see more similarities is at work: 63% say men and women are basically similar when it comes to the things they are good at in the workplace, while 37% say they are mostly different. Men and women express similar views on this.

Among Democrats, there is a clear sense that men and women are similar when it comes to the things they are good at in the workplace: 69% say this is the case, while 30% say men and women are basically different in this regard. While Republicans are more divided, more see similarities (55%) than differences (44%) in the things men and women are good at in the workplace.

Millennial men are far more likely than those in older generations to say men face pressure to throw a punch if provoked, join in when others talk about women in a sexual way, and have many sexual partners

Most men say men in general face at least some pressure to be emotionally strong (86%) and to be interested in sports (71%); about six-in-ten (57%) say men face pressure to be willing to throw a punch if provoked, while smaller but sizable shares of men say men face pressure to join in when other men are talking about women in a sexual way (45%) and to have many sexual partners (40%).

Millennial men stand out from their older counterparts in three of these areas: 69% say there is at least some pressure on men to be willing to throw a punch; 55% of Gen X and 53% of Boomer men and even smaller shares of men in the Silent Generation (34%) say men face pressure in this regard. And while about six-in-ten Millennial men say there is at least some pressure on men in general to have many sexual partners (61%) and to join in when other men are talking about women in a sexual way (57%), about four-in-ten or fewer older men say men face at least some pressure in these areas.

While the question asked about pressures men face in general, it is possible that respondents were drawing on their or their friends’ personal experiences when answering. As such, the generational gaps in views of how much pressure men face in these realms may reflect, at least in part, their age and their stage in life.

Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say society values masculinity – and also more likely to see this as a bad thing

About six-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (58%) say most people in our society these days look up to men who are manly or masculine, while 4% say society looks down on these men and 37% say it neither looks up to nor down on them. Among Republicans and those who lean to the Republican Party, 47% say society looks up to masculine men; 12% say society looks down on them and 41% say neither answer applies.

About six-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (58%) say most people in our society these days look up to men who are manly or masculine, while 4% say society looks down on these men and 37% say it neither looks up to nor down on them. Among Republicans and those who lean to the Republican Party, 47% say society looks up to masculine men; 12% say society looks down on them and 41% say neither answer applies.

Republicans who say society looks up to masculine men overwhelmingly say this is a good thing (78%). Democrats aren’t convinced: Among those who say society looks up to masculine men, almost identical shares say this is a good thing (49%) as say it is a bad thing (48%).

While smaller shares of Americans say most people in our society look up to feminine women than say most people look up to masculine men, a solid majority of those who say society looks up to women who are feminine (83%) also say this is a good thing; just 15% say it’s a bad thing that society looks up to feminine women. Overall, 60% of those who say most people look up to masculine men see this as a good thing, while 37% say it is bad.

Race and educational attainment are linked to how people see their own masculinity or femininity

Men and women give similar answers when asked to describe themselves in terms of their own masculinity or femininity. About three-in-ten men (31%) say they are very manly or masculine, while 54% describe themselves as somewhat masculine and 15% say they are not too or not at all masculine. Among women, 32% say they are very womanly or feminine, 54% say they are somewhat feminine and 14% say they are not too or not at all feminine.

Men and women give similar answers when asked to describe themselves in terms of their own masculinity or femininity. About three-in-ten men (31%) say they are very manly or masculine, while 54% describe themselves as somewhat masculine and 15% say they are not too or not at all masculine. Among women, 32% say they are very womanly or feminine, 54% say they are somewhat feminine and 14% say they are not too or not at all feminine.

Black men are more likely than white men to say they are very masculine, and the same pattern holds for women. About half of black men (49%) and black women (47%) describe themselves as either very masculine or very feminine, compared with 28% of white men who say they are very masculine and 27% of white women who see themselves as very feminine. While about a third of men and women without a four-year college degree say they are very masculine or feminine (34% each), smaller shares of those who have a bachelor’s degree or more education describe themselves this way (22% and 24%, respectively).

The survey also finds a wide generational gap in the way women see their own femininity. While about half (53%) of women in the Silent Generation say they are very feminine, about a third of Boomer (36%) and Gen X (32%) women and an even smaller share of Millennial women (19%) see themselves this way. There is no clear link between a man’s age and the way he sees his masculinity.

Among men, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say they are very manly or masculine: 39% of Republican men – vs. 23% of their Democratic counterparts – describe themselves this way. And while 21% of Democratic men say they are not too or not at all masculine, just 8% of Republican men say the same. Views are more uniform across party lines when it comes to how women see themselves.

When it comes to raising children, more see advantages in exposing girls than boys to activities typically associated with the other gender

Most adults are open to the idea of exposing young girls and boys to toys and activities that are typically associated with the opposite gender. About three-quarters (76%) say it’s a good thing for parents of young girls to encourage their daughters to play with toys or participate in activities that are typically associated with boys; a somewhat smaller majority (64%) says it’s a good thing for parents of young boys to encourage them to play with toys or participate in activities usually thought of as being for girls.

Most adults are open to the idea of exposing young girls and boys to toys and activities that are typically associated with the opposite gender. About three-quarters (76%) say it’s a good thing for parents of young girls to encourage their daughters to play with toys or participate in activities that are typically associated with boys; a somewhat smaller majority (64%) says it’s a good thing for parents of young boys to encourage them to play with toys or participate in activities usually thought of as being for girls.

Women are more likely than men to say parents should encourage their children to engage in activities that are typically associated with the opposite gender, but the difference is more pronounced when it comes to views about raising boys. Large majorities of women (80%) and men (72%) say it’s a good thing for parents of young girls to do this; 71% and 56%, respectively, say parents of young boys should encourage them to play with toys or participate in activities typically associated with girls.

Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are more likely than Republicans and those who lean Republican to say it’s good for parents to break with gender norms in raising children, and here, too, the difference is most pronounced when it comes to raising boys. About eight-in-ten Democrats (78%) – vs. 47% of Republicans – say it’s a good thing for parents of young boys to encourage them to play with toys and participate in activities typically associated with girls.

Americans differ over what should be emphasized in raising boys vs. girls

Americans offer different assessments of how boys and girls are being raised these days when it comes to specific traits and behaviors. The biggest gap can be seen in encouraging children to talk about their feelings when they are sad or upset: 59% of adults say there is too little emphasis on encouraging boys to talk about their feelings, while only 38% say the same about girls (51% say things are about right in this area when it comes to girls). And while 51% say there should be more emphasis on encouraging boys to do well in school, somewhat smaller shares (43%) say there should be more emphasis on this for girls.

Americans offer different assessments of how boys and girls are being raised these days when it comes to specific traits and behaviors. The biggest gap can be seen in encouraging children to talk about their feelings when they are sad or upset: 59% of adults say there is too little emphasis on encouraging boys to talk about their feelings, while only 38% say the same about girls (51% say things are about right in this area when it comes to girls). And while 51% say there should be more emphasis on encouraging boys to do well in school, somewhat smaller shares (43%) say there should be more emphasis on this for girls.

When it comes to what’s lacking for girls these days, more Americans say there is too little emphasis on encouraging girls to be leaders and to stand up for themselves than say there is too little emphasis when it comes to encouraging boys in these areas. About half say more should be done to encourage girls to be leaders (53%) and to stand up for themselves (54%), compared with about four-in-ten who say the same about encouraging boys to do each of these.

Women are more likely than men to say there is too little emphasis on encouraging girls to be leaders: 57% of women say this, compared with 49% of men. But when it comes to encouraging leadership in boys, views are reversed, with larger shares of men (46%) than women (38%) saying there should be more emphasis on this.

There is a party split on this issue as well. Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to say there is too little emphasis on leadership for girls – 64% of Democrats say this compared with 39% of Republicans. For their part, a majority of Republicans (56%) say there is too little emphasis on this trait for boys; only 30% of Democrats agree.

All references to party affiliation include those who lean toward that party: Republicans include those who identify as Republicans and independents who say they lean toward the Republican Party, and Democrats include those who identify as Democrats and independents who say they lean toward the Democratic Party.

References to Millennials include adults who are ages 18 to 36 in 2017. Generation Xers include those who are ages 37 to 52, Baby Boomers include those who are 53 to 71 and members of the Silent Generation include those ages 72 to 89.

References to college graduates or people with a college degree comprise those with a bachelor’s degree or more. “Some college” includes those with an associate degree and those who attended college but did not obtain a degree. “High school” refers to those who have a high school diploma or its equivalent, such as a General Education Development (GED) certificate.

References to whites and blacks include only those who are non-Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

Essay: Strong men, caring women

Essay: Strong men, caring women