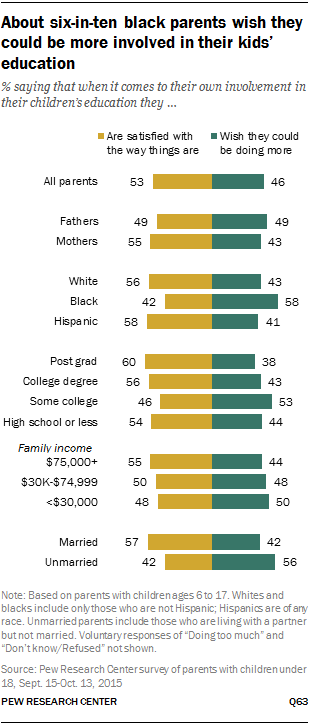

Many parents say that too much parental involvement in a child’s education can be a bad thing, and about half of those with school-age children say they are satisfied with the level of their own involvement in their children’s education. Still, more than four-in-ten say they wish they could be more involved. This is particularly the case among black parents; about six-in-ten say they would like to be more involved, compared with about four-in-ten white and Hispanic parents.

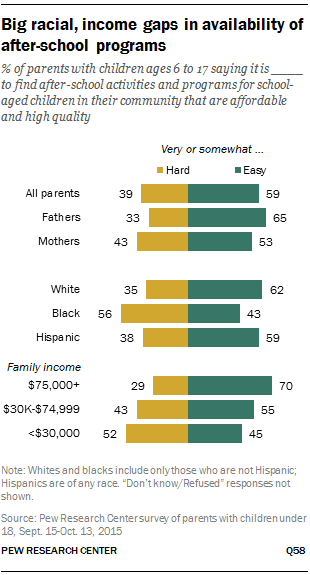

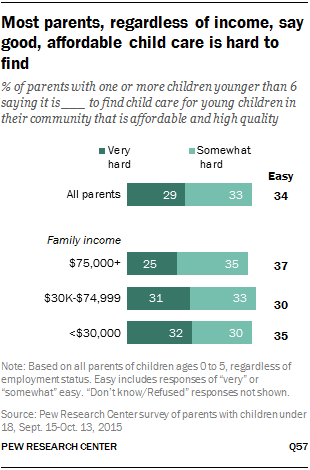

Child care is a major concern for parents with children who are not yet school age. A majority of parents with one or more children younger than 6 say it’s hard to find high-quality, affordable child care in their community. Among parents with school-age children, about four-in-ten say it’s hard to find after-school activities and programs that are both affordable and high quality. Black parents – as well as those with lower incomes – are more likely than other parents to say this is a challenge for them.

This chapter explores parents’ involvement in their children’s education and school activities, as well as child care and after-school arrangements, across different socioeconomic and racial groups. It also looks at parents’ approaches to education, including how much pressure they put on their children to succeed academically and whether they would be disappointed if their children got average grades.

Parents have mixed views about children’s academic performance

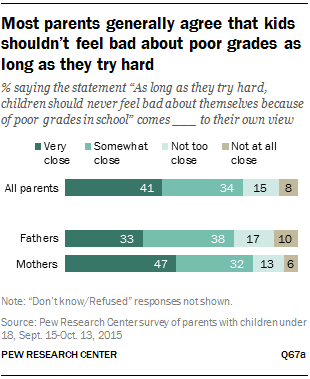

Parents generally feel that children should never feel bad about themselves because of poor grades in school as long as they try hard; 41% say this is very close to their view, and an additional 34% say it is somewhat close. Still, about a quarter (23%) of parents say this is not too close or not at all close to their opinion.

Parents generally feel that children should never feel bad about themselves because of poor grades in school as long as they try hard; 41% say this is very close to their view, and an additional 34% say it is somewhat close. Still, about a quarter (23%) of parents say this is not too close or not at all close to their opinion.

Mothers are more likely than fathers to say the sentiment that kids shouldn’t feel bad about their academic performance as long as they try hard is very close to their own view; about half (47%) of moms say this, compared with a third of dads.

There are no significant differences on this question across generations or racial, educational or income groups, but there is a difference in how parents with different ideological leanings approach this. Fully half of parents who describe themselves as politically liberal say the notion that children should never feel bad about themselves because of poor grades as long as they try hard is very close to their own view; fewer conservative (39%) and moderate (32%) parents say this is the case. Despite this ideological difference, partisan splits are not evident on this question.

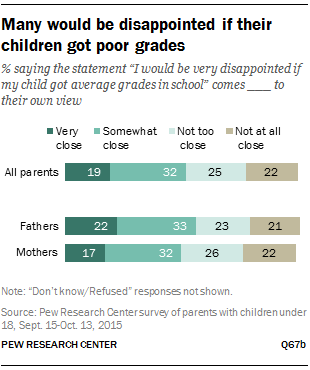

While parents generally agree that children shouldn’t feel bad about themselves because of poor grades as long as they make an effort, many say they would be very disappointed if their child got average grades in school. About one-in-five say this is very close (19%) to the way they feel, and about a third (32%) say it is somewhat close. Somewhat more fathers (22%) than mothers (17%) say this comes very close to their view, but about half in each group say it is at least somewhat close.

While parents generally agree that children shouldn’t feel bad about themselves because of poor grades as long as they make an effort, many say they would be very disappointed if their child got average grades in school. About one-in-five say this is very close (19%) to the way they feel, and about a third (32%) say it is somewhat close. Somewhat more fathers (22%) than mothers (17%) say this comes very close to their view, but about half in each group say it is at least somewhat close.

Parents who have a bachelor’s degree are considerably more likely than those who don’t to say that the statement, “I would be very disappointed if my child got average grades in school” comes at least somewhat close to their own view; 60% among college graduates say this, compared with 45% of parents with some college and 48% of those with a high school diploma or less. Similarly, parents with annual family incomes of $75,000 or higher are more likely than those with lower incomes to say this comes at least somewhat close to their view (58% vs. 47% of those with incomes under $30,000).

Most parents say they put the right amount of pressure on their kids

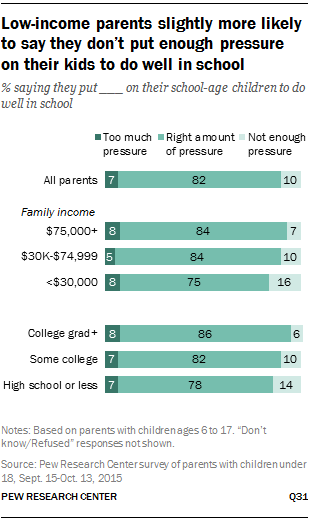

The large majority of American parents with school-age children say they put the right amount of pressure on their kids to do well in school (82%), but one-in-ten say they don’t put enough pressure on their kids, and 7% say they exert too much pressure.

The large majority of American parents with school-age children say they put the right amount of pressure on their kids to do well in school (82%), but one-in-ten say they don’t put enough pressure on their kids, and 7% say they exert too much pressure.

Parents who do not have a college degree are twice as likely as those who do to say they don’t put enough pressure on their kids to do well in school (12% vs. 6%), although about three-quarters or more across education groups say they put the right amount of pressure on their kids. Similarly, those with lower incomes are slightly more likely than those with higher incomes to say they could be putting more academic pressure on their kids; 16% of those with annual family incomes below $30,000 say this, compared with 10% of those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and 7% of those with incomes of $75,000 or higher.

Most parents are satisfied with the quality of education their kids are getting

Half of parents with school-age children say they are very satisfied with the quality of education their children are receiving at school, and an additional 36% are somewhat satisfied; just 13% say they are very (4%) or somewhat (9%) dissatisfied.

For many parents, opinions about the quality of education at their kids’ schools and views about their neighborhoods go hand in hand. Six-in-ten parents with school-age children who describe their neighborhood as an excellent place to raise kids say they are very satisfied with the education their kids are getting. About half (52%) of those who say their neighborhood is a very good place to raise kids, and fewer among those who rate their neighborhood as good (39%) or fair or poor (40%), are very satisfied with the quality of education their children are receiving.

Hispanic parents are more likely than white or black parents to say they are very satisfied with the quality of education at their kids’ schools (62% vs. 49% and 48%, respectively).

Can too much parental involvement in a child’s education be a bad thing?

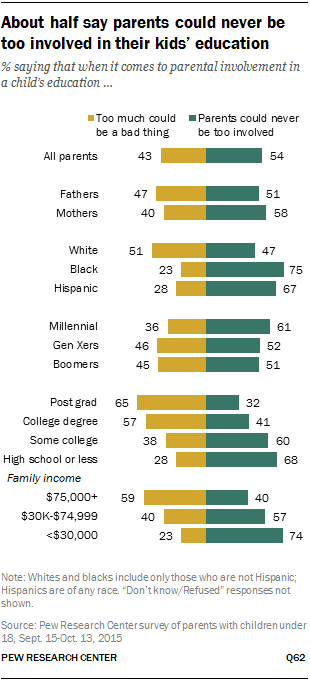

About half (54%) of American parents say parents can never be too involved when it comes to their children’s education, but about four-in-ten (43%) say too much involvement could be a bad thing. Mothers are somewhat less likely than fathers to say too much parental involvement in a child’s education could be a bad thing (40% vs. 47%).

About half (54%) of American parents say parents can never be too involved when it comes to their children’s education, but about four-in-ten (43%) say too much involvement could be a bad thing. Mothers are somewhat less likely than fathers to say too much parental involvement in a child’s education could be a bad thing (40% vs. 47%).

Views about parental involvement in a child’s education also vary by race and ethnicity, with white parents far more likely than black or Hispanic parents to say too much can be a bad thing. About as many whites say this (51%) as say a parent could never be too involved (47%). In contrast, only 23% of black parents and 28% of Hispanic parents think too much parental involvement in a child’s education could be a bad thing, while 75% and 67%, respectively, say parents could never be too involved.

Parents with a bachelor’s degree, as well as those with higher incomes, are more likely than those with less education and lower incomes to say too much parental involvement in a child’s education could be a bad thing. Six-in-ten college graduates say this, compared with 38% of parents with some college and 28% of parents with a high school diploma or less. On the flip side, at least six-in-ten of those with some college (60%) or no college (68%) say one could never be too involved, compared with 37% of parents with a college degree or more. But even among parents who have graduated from college, those with a post-graduate degree are more likely than those without to say too much parental involvement in their kids’ education could be a bad thing (65% vs. 57%).

Similarly, 59% of parents with an annual family income of $75,00o or higher say too much involvement could have negative effects. Four-in-ten parents with family incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and even fewer (23%) among those with an income under $30,000 share this view.

Across generations, Millennials are more likely than older parents to say parents could never be too involved in their children’s education, but these differences are driven primarily by the views of Millennial moms. Overall, 61% of Millennial parents say one could never be too involved, compared with 52% of Gen X parents and 51% of Boomer parents. Like mothers and fathers in older generations, about half (51%) of Millennial dads say parents could never be too involved in their children’s education; 66% of Millennial moms share this view.

About half of parents wish they could be more involved

When it comes to assessments of their own involvement in their kids’ education, close to half (46%) of parents of school-age children say they wish they could be doing more, although somewhat more (53%) say they are satisfied with the way things are. Dads are somewhat more likely than moms to say they wish they could be more involved in their kids’ education (49% vs. 43%).

When it comes to assessments of their own involvement in their kids’ education, close to half (46%) of parents of school-age children say they wish they could be doing more, although somewhat more (53%) say they are satisfied with the way things are. Dads are somewhat more likely than moms to say they wish they could be more involved in their kids’ education (49% vs. 43%).

Self-assessments also differ by race and ethnicity. About six-in-ten (58%) black parents wish they could be doing more when it comes to their children’s education, compared with about four-in-ten white (43%) and Hispanic (41%) parents. There is not a clear link between parents’ education or income and assessments of their involvement in their children’s education.

Unmarried parents are more likely than those who are married to say they wish they could be doing more when it comes to their children’s education. While about four-in-ten (42%) married parents would like to be more involved in their children’s education, 56% of those who are unmarried say this is the case.

Unmarried parents are more likely than those who are married to say they wish they could be doing more when it comes to their children’s education. While about four-in-ten (42%) married parents would like to be more involved in their children’s education, 56% of those who are unmarried say this is the case.

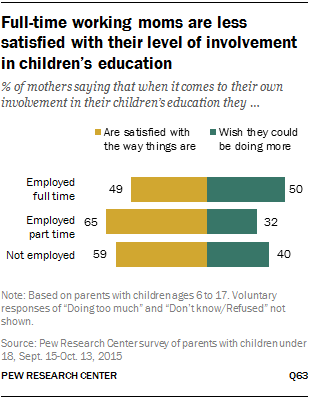

Moms who work full time are more likely than those who work part time or are not employed to say they wish they could be more involved in their children’s education (50% vs. 32% and 40%, respectively). Among dads, however, there is no significant difference in the shares of those who are employed full time (49%) and those who are employed part time or not employed (53%) saying they wish they could be doing more when it comes to involvement in their children’s education.22

Most parents say they’re involved with school-related activities

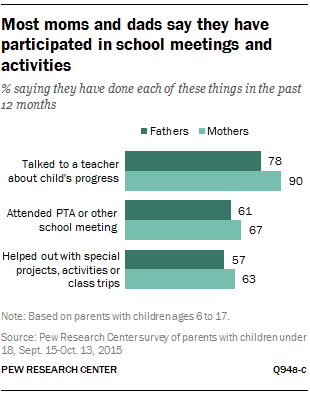

More than eight-in-ten (85%) parents with one or more school-age children say they talked to a teacher about their children’s academic progress in the 12 months prior to the survey, and at least six-in-ten attended a PTA or other special school meeting (64%) or helped out with special projects, activities or a class trip at school (60%). Overall, about four-in-ten (43%) say they did all three of these activities in the year prior to the survey, while about half (49%) did one or two, and just 8% were not engaged in any of these school-related activities.

More than eight-in-ten (85%) parents with one or more school-age children say they talked to a teacher about their children’s academic progress in the 12 months prior to the survey, and at least six-in-ten attended a PTA or other special school meeting (64%) or helped out with special projects, activities or a class trip at school (60%). Overall, about four-in-ten (43%) say they did all three of these activities in the year prior to the survey, while about half (49%) did one or two, and just 8% were not engaged in any of these school-related activities.

Moms are somewhat more likely than dads to say they participated in each of these activities in the previous 12 months, although majorities in both groups say they have done each of these things.

For example, nine-in-ten mothers with school-age children say they talked to a teacher about their children’s academic progress in the 12 months prior to the survey, compared with 78% of fathers with kids in the same age group. Similarly, 67% of moms say they attended a PTA meeting or other special school meeting and 63% helped out with special projects, activities or class trips; among dads, 61% say they attended a school meeting and 57% say they volunteered to help out with a special project or activity.

White parents are somewhat more likely than black or Hispanic parents to say they helped out with a special project, activity or class trip in the 12 months before the survey (63% vs. 56% and 51%, respectively). But a larger share of black parents (75%) than white parents (63%) say they attended a PTA meeting or other special school meeting over that period; 68% of Hispanic parents say they did this.

Across socioeconomic groups, parents with higher incomes and those who attended college are far more likely than those with lower incomes and those with a high school education or less to say they helped out with special projects, activities or a class trip at their children’s school during the 12 months prior to the survey. About seven-in-ten higher-income and college-educated parents (69% each) say they did this over that period, compared with about half of those with annual family incomes less than $30,000 and those who did not attend college.

Parents with at least some college experience are also more likely than other parents to say they attended a PTA or other school meetings or talked to a teacher about their children’s progress in the 12 months before the survey. When it comes to participation in these activities, differences across income groups is modest at best.

After-school arrangements vary by income

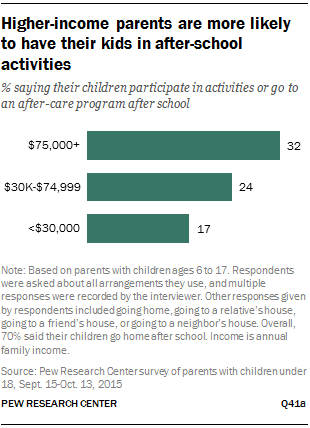

Seven-in-ten parents say their school-age children go home after school, while about a quarter say they participate in after-school activities (18%) or use an after-care program (8%). Parents with higher incomes are more likely than those with lower incomes to say their children participate in after-school activities or go to an after-care program; 32% of those with annual family incomes of $75,000 or higher use one of these options, compared with 24% of those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and 17% of those with incomes below $30,000. Parents with incomes below $30,000 are more likely to say their children go home after school; about eight-in-ten (79%) say this, compared with about two-thirds of those with higher incomes.

Seven-in-ten parents say their school-age children go home after school, while about a quarter say they participate in after-school activities (18%) or use an after-care program (8%). Parents with higher incomes are more likely than those with lower incomes to say their children participate in after-school activities or go to an after-care program; 32% of those with annual family incomes of $75,000 or higher use one of these options, compared with 24% of those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and 17% of those with incomes below $30,000. Parents with incomes below $30,000 are more likely to say their children go home after school; about eight-in-ten (79%) say this, compared with about two-thirds of those with higher incomes.

Parents of teenagers are more likely than those whose only or oldest child is ages 6 to 12 to say their children participate in after-school activities (22% vs. 12%), while after-care programs are a more popular option for those with younger school-age kids than for those whose oldest child is a teenager (13% vs. 4%).

Perhaps not surprisingly, parents in two-parent households where both parents work full time are more likely than those in families where one works full time and one works part time and families where only one parent is working outside of the home to use after-care programs (11% vs. 3% and 4%, respectively). But about the same shares of parents in families where both parents work full time (22%) and in families with one parent who works full time and one who works part time (25%) say their children participate in after-school activities; just 9% of families with one parent at home say this. In these families, 79% say their kids go home after school, compared with 68% in families where both parents work at least part time.

For some parents, good after-school programs can be hard to find

Most parents of school-aged children are upbeat about the availability of after-school activities in their community, although many say affordable, high-quality programs are hard to find. Roughly six-in-ten parents with children ages 6 to 17 say it is very (25%) or somewhat (34%) easy to find affordable, high-quality after-school activities and programs for school-aged children in their community. About four-in-ten say it is very (14%) or somewhat (25%) hard to find these activities.

Most parents of school-aged children are upbeat about the availability of after-school activities in their community, although many say affordable, high-quality programs are hard to find. Roughly six-in-ten parents with children ages 6 to 17 say it is very (25%) or somewhat (34%) easy to find affordable, high-quality after-school activities and programs for school-aged children in their community. About four-in-ten say it is very (14%) or somewhat (25%) hard to find these activities.

Mothers (43%) are somewhat more likely than fathers (33%) to say it’s difficult to find good after-school activities where they live. And there are major gaps by race and socioeconomic status. Many black parents (56%) with school-aged children say it is hard to find affordable, high-quality after-school programs in their community; only 43% say this is easy. By contrast, about six-in-ten white (62%) and Hispanic parents (59%) say it’s easy to find these types of activities for school-aged kids where they live.

Parents from lower-income families have a more negative assessment of the availability of after-school programs in their communities than parents in higher-income families. Among parents with school-aged children who say their annual family income is less than $30,000, 52% say it is hard to find high-quality, affordable after-school programs where they live; 45% say this is easy. Parents from middle-income families lean in the opposite direction, with 55% saying it’s easy to find these after-school activities and 43% saying it’s hard. Parents with family incomes in excess of $75,000 have a much more positive view: 70% say it’s easy (and 29% say it’s hard) to find affordable, high-quality activities for school-aged children where they live.

Finding affordable, high-quality day care

About half (48%) of working parents with at least one child younger than 6 say their children attend day care or preschool, while 45% say their kids are cared for by a family member when the parents are at work, and 16% rely on a nanny or babysitter.

About half (48%) of working parents with at least one child younger than 6 say their children attend day care or preschool, while 45% say their kids are cared for by a family member when the parents are at work, and 16% rely on a nanny or babysitter.

White parents with young children are more likely than non-white parents to say their kids attend day care or preschool (55% vs. 39%). Those with annual family incomes of $75,000 or more are about twice as likely as those with lower incomes to say their young children are in this type of child care arrangement (66% vs. 32%). In turn, those with incomes below $75,000 are far more likely than those with higher incomes to rely on a family member to care for their children while they are at work (57% vs. 35%).23

Child care can be a major expense for working parents, and the cost has gone up significantly in recent years. Census data show that average weekly child care expenses for families with working mothers increased from $84 per week in 1985 to $143 per week in 2011 (both in 2011 dollars).24 And the burden of child care costs falls more heavily on lower-income parents, as it takes up a larger proportion of their household earnings.

The challenges parents face in finding and affording child care for their young children are reflected in one striking finding from the survey: A majority of parents with one or more children younger than 6 say it is very (29%) or somewhat (33%) hard to find affordable, high-quality child care in their community. Mothers and fathers agree on this point. And there are few differences among parents from different races, income groups or educational backgrounds.

Unmarried parents are more likely than those who are married to say that it’s hard to find high quality, affordable day care where they live (70% vs. 58%). And families with two full-time working parents – who are highly likely to be in need of child care – are much more likely to say this is a challenge in their community than are those in families in which one of the parents does not work outside of the home. Among parents in families where both the mother and father work full time, 67% say it’s hard to find affordable, high-quality day care where they live. By comparison, some 53% of in families with a parent at home say the same.

How involved are parents in their young kids’ education?

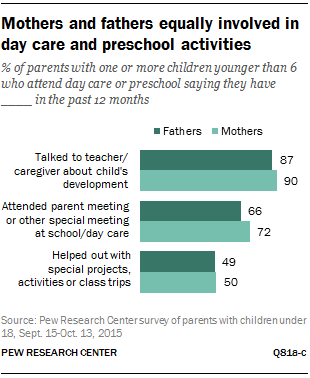

Nearly half (45%) of parents with at least one child younger than 6 say that they have a child who attends a day care, preschool or pre-kindergarten program. An overwhelming majority of these parents (89%) say that, in the 12 months prior to the survey, they talked to a teacher or caregiver at their child’s day care or preschool about their child’s development. Mothers (90%) and fathers (87%) are about equally likely to say they did this.

Nearly half (45%) of parents with at least one child younger than 6 say that they have a child who attends a day care, preschool or pre-kindergarten program. An overwhelming majority of these parents (89%) say that, in the 12 months prior to the survey, they talked to a teacher or caregiver at their child’s day care or preschool about their child’s development. Mothers (90%) and fathers (87%) are about equally likely to say they did this.

About seven-in-ten (69%) parents whose children younger than 6 are enrolled in day care or preschool say they attended a parent meeting or other special meeting at the facility in the year leading up to the survey. Again, similar shares of mothers (72%) and fathers (66%) say they did this.

Half of parents with young children in day care or preschool say they helped out with special projects, activities or class trips in the year prior to the survey.

Half of parents read to their young children daily

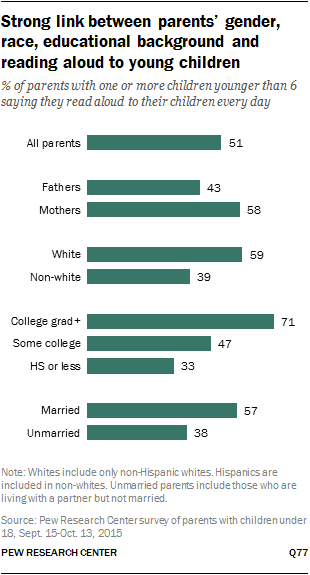

Among all parents with at least one child under the age of 6, 51% say that they read aloud to their young children every day. An additional 31% say that they read to their children a few times a week. Some 8% say that they do this about once a week, and 9% say they read aloud less often than that.

Among all parents with at least one child under the age of 6, 51% say that they read aloud to their young children every day. An additional 31% say that they read to their children a few times a week. Some 8% say that they do this about once a week, and 9% say they read aloud less often than that.

There is a significant gender gap on this item: Mothers (58%) are more likely than fathers (43%) to say that they read to their young children every day.

White parents with young children are significantly more likely than non-white parents to say that they read to their young children daily. About six-in-ten (59%) white parents say they read aloud to their kids every day, compared with 39% of non-white parents. A higher share of non-white parents than white parents say they read to their children a few times a week (39% vs. 27%).

Parents with a bachelor’s degree are among the most likely to say they read aloud to their young children every day – 71% say they do. By comparison, 47% of parents with some college education and 33% of those with a high school diploma or less say they do the same.

Finally, while about six-in-ten married parents (57%) say they read to their infants or preschoolers on a daily basis, only 38% of unmarried parents say they do.