Economic optimism

Coming of age during the country’s deepest economic downturn since the Great Depression has made it much more difficult for Millennials to find their financial footing. And they are still dealing with the fallout from the recession and sluggish recovery. The unemployment rate remains high for this generation—especially those ages 18 to 24, 13% of whom were unemployed in January 2014.16 The share of young adults living in their parents’ home reached an historic high in 2012, three years after the recession had ended. And while the importance of a college degree has grown, so has the cost. As a result, Millennials are more burdened with student debt than any previous generation of young adults.

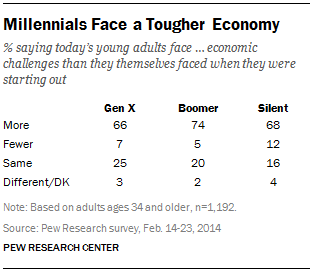

None of this is lost on the public, as solid majorities of Gen Xers (66%), Boomers (74%) and Silents (68%) say young adults today face more economic challenges than they themselves faced when they were first starting out. And Millennials have a similar view. Roughly seven-in-ten Millennials (71%) say that people their age face more economic challenges compared with their parents’ generation when they were young.

None of this is lost on the public, as solid majorities of Gen Xers (66%), Boomers (74%) and Silents (68%) say young adults today face more economic challenges than they themselves faced when they were first starting out. And Millennials have a similar view. Roughly seven-in-ten Millennials (71%) say that people their age face more economic challenges compared with their parents’ generation when they were young.

Among Millennials, there is broad agreement across major demographic subgroups that today’s young adults face greater economic challenges than their parents’ generation faced when they were starting out. Millennial men and women agree on this, as do Millennials with annual family incomes of $75,000 or more and those with family incomes of less than $35,000, and those with and without a college degree.

The economic challenges they face may be causing Millennials to reassess their place in the broader economy. A January 2014 Pew Research poll found that only 42% of Millennials now identify themselves as “middle class.” This is down significantly from 2008 when 53% said they were middle class. Perhaps more strikingly, fully 46% of Millennials describe themselves as lower or lower-middle class in the recent survey, up from 25% in 2008.

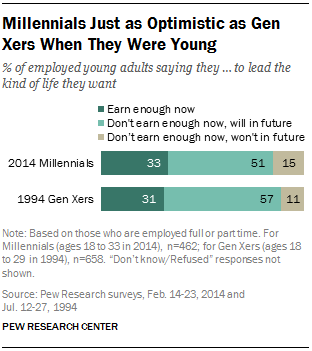

In spite of the difficult economic hand they have been dealt, Millennials are remarkably optimistic about their future prospects. While they are not as satisfied with their current financial situation as are their older counterparts, they are much more upbeat about their financial futures. Among Millennials who are employed, only 33% in the current poll say they now earn enough to lead the kind of life they want, but fully half (51%) say they will be able to earn enough in the future.

In spite of the difficult economic hand they have been dealt, Millennials are remarkably optimistic about their future prospects. While they are not as satisfied with their current financial situation as are their older counterparts, they are much more upbeat about their financial futures. Among Millennials who are employed, only 33% in the current poll say they now earn enough to lead the kind of life they want, but fully half (51%) say they will be able to earn enough in the future.

In this regard Millennials are about as optimistic about their financial futures as Gen Xers were when they were a comparable age. A 1994 Pew Research survey found that among employed Gen Xers (who were under age 30 at the time), 31% said they were earning enough to live the kind of life they wanted, an additional 57% said they weren’t earning enough but expected to in the future. Gen Xers were coming of age in a much more favorable economic environment than today’s Millennials find themselves.

In this regard Millennials are about as optimistic about their financial futures as Gen Xers were when they were a comparable age. A 1994 Pew Research survey found that among employed Gen Xers (who were under age 30 at the time), 31% said they were earning enough to live the kind of life they wanted, an additional 57% said they weren’t earning enough but expected to in the future. Gen Xers were coming of age in a much more favorable economic environment than today’s Millennials find themselves.

Millennials who are not currently employed are equally bullish about their financial futures. While only 29% say they now have enough income to lead the kind of life they want, a majority (59%) believe they will have enough income in the future.

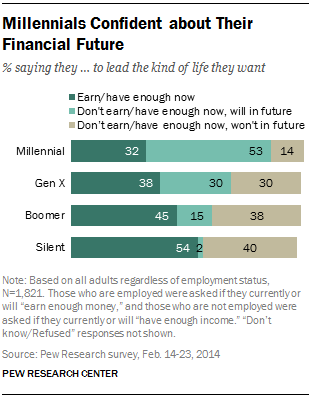

Taken together, 85% of Millennials (both employed and not employed) say that they either have enough earnings or income now to lead the kind of life they want or they believe they will in the future. Only 14% say they don’t have enough money now and don’t anticipate that they will in the future. By comparison, 68% of Gen Xers say they have enough money now or expect to in the future, 60% of Boomers say the same as do 56% of Silents.

Among Millennials, men and women are equally optimistic about their financial futures. College-educated Millennials are much more likely than those without a college degree to say they have enough money now to lead the kind of life they want (52% vs. 26%). And while those without a college degree are more likely to say they are optimistic about their future finances, it is not quite enough to fill the gap. Overall, 91% of college-educated Millennials have or think they will have enough money, compared with 83% of Millennials with less education.

Generations Differ Over Key Societal Trends

There are sharp age gaps in attitudes when it comes to several of the major social and demographic changes shaping the country today. In some instances, Millennials are more likely than their older counterparts to say these changes are good for society. In other realms, they are more likely to take a “live and let live” attitude.

There are sharp age gaps in attitudes when it comes to several of the major social and demographic changes shaping the country today. In some instances, Millennials are more likely than their older counterparts to say these changes are good for society. In other realms, they are more likely to take a “live and let live” attitude.

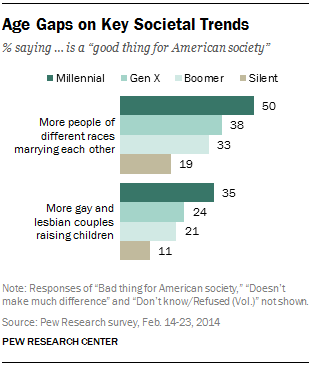

Respondents were asked about six trends and whether each was a good thing for American society, a bad thing for American society or didn’t make much difference for society. When compared with older generations, Millennials have a much more positive view of the rise in interracial marriage. Fully 50% of Millennials say the trend toward more people of different races marrying each other is good for society. By comparison, 38% of Gen Xers, 33% of Boomers and only 19% of Silents say the same. Roughly one-in-five Silents (21%) say this trend is bad for society, compared with just 7% among all younger adults. Among Millennials, whites (49%) and non-whites (50%) are equally likely to view this as a positive trend. In contrast, among older adults, non-whites are more likely than whites to see this as a good thing for society (40% vs. 29%).

Similarly, Millennials are much more accepting of gay and lesbian couples raising children. Some 35% of Millennials say this trend is good for society. Among Gen Xers, 24% view this as a positive trend, 21% of Boomers say this is a good thing, as do 11% of Silents. Only 17% of Millennials say this is a bad thing for society, compared with 39% of all older adults.

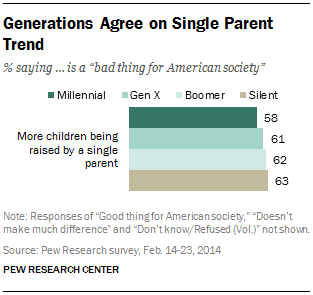

Another key trend in the realm of marriage and family is the rising share of children being raised by a single parent. There is general agreement across the generations that this trend is not a good thing for society. Fully 58% of Millennials say this is bad for society, and similar shares of Gen Xers (61%), Boomers (62%) and Silents (63%) concur. Very few adults of any age say this trend is good for society.

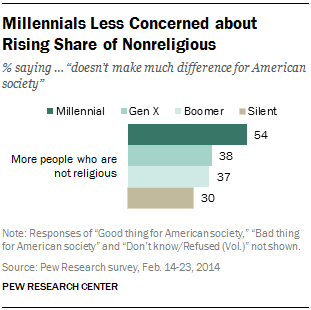

When it comes to changing patterns in religious affiliation and commitment, Millennials tend to take a more neutral position compared with adults from older generations. Relatively few Millennials (13%) say that having more people who are not religious is a good thing for society, but a plurality (54%) say this trend doesn’t make much difference. Pluralities of Gen Xers and Boomers say this trend is bad for society, as do 57% of Silents.

When it comes to changing patterns in religious affiliation and commitment, Millennials tend to take a more neutral position compared with adults from older generations. Relatively few Millennials (13%) say that having more people who are not religious is a good thing for society, but a plurality (54%) say this trend doesn’t make much difference. Pluralities of Gen Xers and Boomers say this trend is bad for society, as do 57% of Silents.

Among Millennials, those with a college degree are about twice as likely as those without a college degree to say the growing number of people who are not religious is a good thing for society (21% vs. 10%).

Among Millennials, those with a college degree are about twice as likely as those without a college degree to say the growing number of people who are not religious is a good thing for society (21% vs. 10%).

Respondents were also asked about two important generational trends. The first is the trend toward more young adults living with their parents. There is no consensus within any generation as to whether this is a good thing or a bad thing for society. Boomers are somewhat more likely than Millennials to say this is a good thing for society (22% vs. 17%). Millennials themselves are evenly divided over whether this trend is bad for society (41%) or doesn’t make much difference (40%).

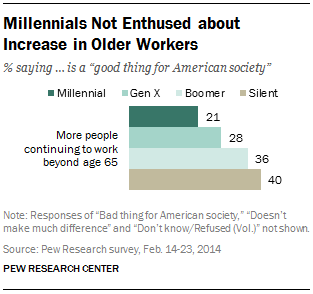

At the other end of the generational spectrum, respondents were asked whether the trend toward more people continuing to work beyond age 65 was good or bad for society. Gen Xers, Boomers and Silents are significantly more likely than Millennials to view this as a positive trend. Millennials, who have struggled mightily in the labor market, are more than twice as likely as Silents to say this trend is bad for society (47% vs. 21%).

At the other end of the generational spectrum, respondents were asked whether the trend toward more people continuing to work beyond age 65 was good or bad for society. Gen Xers, Boomers and Silents are significantly more likely than Millennials to view this as a positive trend. Millennials, who have struggled mightily in the labor market, are more than twice as likely as Silents to say this trend is bad for society (47% vs. 21%).

How the Generations See Themselves

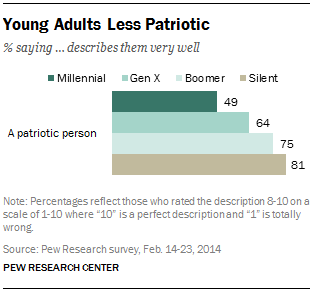

There are sharp differences across age groups in the way adults describe themselves—the labels they choose to embrace or reject. Survey respondents were given a short list of words and phrases and asked how well each one described them. On each of the four descriptions—which cut across different realms of life—Millennials stand apart from the three older generations. They are less likely to see themselves as patriotic, religious or as environmentalists and more likely to say they are supporters of gay rights.

There are sharp differences across age groups in the way adults describe themselves—the labels they choose to embrace or reject. Survey respondents were given a short list of words and phrases and asked how well each one described them. On each of the four descriptions—which cut across different realms of life—Millennials stand apart from the three older generations. They are less likely to see themselves as patriotic, religious or as environmentalists and more likely to say they are supporters of gay rights.

Overall, 65% of adults say that the phrase “a patriotic person” describes them very well, with 35% saying this is a “perfect” description.17 Millennials are much less likely than adults in older generations to embrace this label. About half of Millennials (49%) say this description fits them very well. By comparison, 64% of Gen Xers, 75% of Boomers and 81% of Silents say the same.

Millennials’ relative hesitancy to describe themselves as patriotic may be the result of their stage of life rather than a characteristic of their generation. When Gen Xers were at a comparable age, they were much less likely than their older counterparts to embrace a similar self-description. In a 1999 Pew Research survey, 46% of Gen Xers (ages 19 to 34 at the time) said the word “patriot” described them very well. This compared with 66% among their elders.

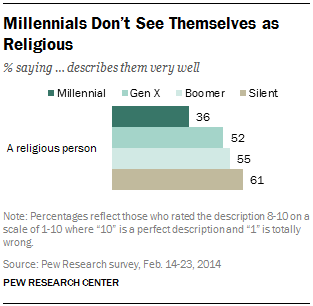

Today’s young adults are also less likely than middle-aged and older adults to describe themselves as religious. Roughly a third (36%) of Millennials say the phrase “a religious person” describes them very well. By comparison, half of Gen Xers (52%) and 55% of Boomers say this description fits them very well. And among Silents, about six-in-ten (61%) say this description fits them very well.

Today’s young adults are also less likely than middle-aged and older adults to describe themselves as religious. Roughly a third (36%) of Millennials say the phrase “a religious person” describes them very well. By comparison, half of Gen Xers (52%) and 55% of Boomers say this description fits them very well. And among Silents, about six-in-ten (61%) say this description fits them very well.

Again, the tendency of Millennials to shy away from this self-description is not unique to this generation of young adults. In 1999, 47% of Gen Xers said that “a religious person” described them very well, compared with 59% of adults ages 35 and older. Still today’s young adults are significantly less likely to identify themselves as religious when compared with Gen Xers at a comparable age (36% vs. 47%).

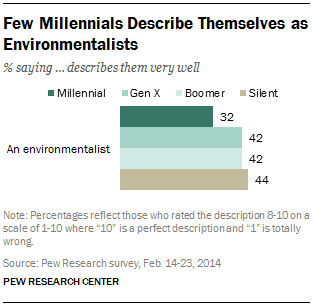

Millennials are also less likely than Gen Xers were in 1999 to identify themselves as “environmentalists.” In 1999, when Gen Xers were under age 35, roughly four-in-ten (39%) embraced this self-description. Today, only about a third of Millennials (32%) say the word “environmentalist” describes them very well. Gen Xers, (42%) Boomers (42%) and Silents (44%) are significantly more likely to embrace this self-description.

Millennials are also less likely than Gen Xers were in 1999 to identify themselves as “environmentalists.” In 1999, when Gen Xers were under age 35, roughly four-in-ten (39%) embraced this self-description. Today, only about a third of Millennials (32%) say the word “environmentalist” describes them very well. Gen Xers, (42%) Boomers (42%) and Silents (44%) are significantly more likely to embrace this self-description.

Public acceptance of gays and lesbians has grown substantially over the past decade, and young adults are at the forefront of these changing views. Fully half of Millennials (51%) say the phrase “a supporter of gay rights” fits them very well. Gen Xers (37%), Boomers (33%) and Silents (32%) are significantly less likely to identify with this description.

The 1999 Pew Research poll asked respondents how well the phrase “a supporter of the gay rights movement” described them. At that time only 17% of all adults said this phrase described them very well. Gen Xers were more likely than their older counterparts to embrace this description: 22% of adults ages 19 to 34 said this was a good description of them compared with 15% of those ages 35 and older. However, this young-old gap has widened considerably since then, from a six percentage point gap between young Gen Xers and older adults in 1999 to a 17 percentage point gap between young Millennials and older adults today.18

The 1999 Pew Research poll asked respondents how well the phrase “a supporter of the gay rights movement” described them. At that time only 17% of all adults said this phrase described them very well. Gen Xers were more likely than their older counterparts to embrace this description: 22% of adults ages 19 to 34 said this was a good description of them compared with 15% of those ages 35 and older. However, this young-old gap has widened considerably since then, from a six percentage point gap between young Gen Xers and older adults in 1999 to a 17 percentage point gap between young Millennials and older adults today.18

Technology Use

One of the widest and most significant gaps between Millennials and older adults is the way they use technology. A 2012 Pew Research survey found that the public sees a larger gap between young and old in technology use than in their moral values, their attitudes about the changing racial and ethnic makeup of the country or the importance they place on family. Fully 64% of the public said young adults and older adults are very different in the way they use the internet and other technology.

One of the widest and most significant gaps between Millennials and older adults is the way they use technology. A 2012 Pew Research survey found that the public sees a larger gap between young and old in technology use than in their moral values, their attitudes about the changing racial and ethnic makeup of the country or the importance they place on family. Fully 64% of the public said young adults and older adults are very different in the way they use the internet and other technology.

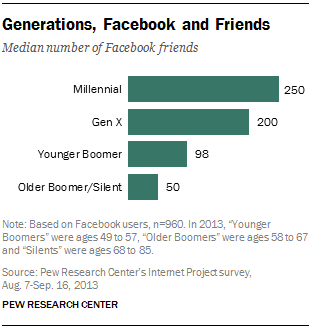

Online social networks are the building blocks of social interaction for many young adults, and these tools have enabled them to create wide-ranging networks of “friends.” Data from the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project show the generational differences in dramatic fashion. Among Facebook users in 2013, Millennials had, on average, 250 Facebook friends. The median number of Facebook friends among Gen Xers was 200, and the numbers fell off steeply from there. For younger Boomers (ages 49 to 57 in 2013), the median number of Facebook friends was 98 and for Older Boomers and Silents it was 50.19

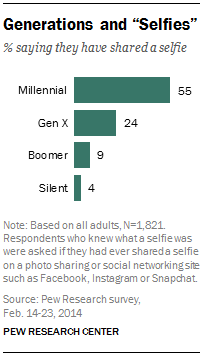

Millennials have led the way on photo sharing as well, so much so that Oxford Dictionaries word of the year for 2013 was “selfie.” Oxford defines selfie as “a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website.” Millennials are much more likely than adults of other generations to be familiar with this term and, not surprisingly, more likely to have posted a selfie on a social networking site.

Millennials have led the way on photo sharing as well, so much so that Oxford Dictionaries word of the year for 2013 was “selfie.” Oxford defines selfie as “a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website.” Millennials are much more likely than adults of other generations to be familiar with this term and, not surprisingly, more likely to have posted a selfie on a social networking site.

About eight-in-ten Millennials (81%) know what a selfie is, and 55% have shared a selfie on a photo sharing or social networking site such as Facebook, Instagram or Snapchat.20 Millennials are more than twice as likely as Gen Xers to have posted a selfie (24% of Gen Xers have done this). And among Boomers and Silents, the shares are considerably smaller (9% of Boomers and 4% of Silents have posted a selfie).

Among Millennials, women are more likely than men to have posted a selfie (68% vs. 42%). There are no significant differences between white and non-white Millennials nor are there differences by educational attainment. Younger Millennials (ages 18 to 25) age more likely than Millennials ages 26 to 33 to have posted a selfie (62% vs. 46%).

While they may like to post pictures of themselves online, Millennials agree with adults from other generations that, in general, people share too much information about themselves on the internet. Overall, 89% of all adults say people share too much personal information online. Roughly equal shares of Millennials (90%), Gen Xers (91%) and Boomers (89%) express this view. Silents are slightly less likely to say people share too much information (81%) and somewhat more likely to have no opinion on this (12%).

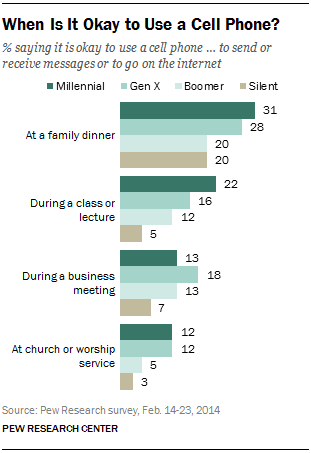

On cell phone usage, there is still a significant generation gap. Nearly all Millennials (96%) and Gen Xers (95%) reported having a cell phone in 2013. Even so, large majorities of Boomers (89%) and Silents (71%) also have cell phones.21 Compared with older adults, Millennials and Gen Xers have somewhat different standards about when and where cell phones should be used. Overall, the public has a fairly stringent view of when it’s appropriate for people to use their cell phones to send or receive messages or go on the internet. The vast majority of adults say it is not okay to use a cell phone at church or worship service (89%), during a class or lecture (82%) or during a business meeting (81%). About seven-in-ten (72%) say it’s not okay to use a cell phone at a family dinner.

On cell phone usage, there is still a significant generation gap. Nearly all Millennials (96%) and Gen Xers (95%) reported having a cell phone in 2013. Even so, large majorities of Boomers (89%) and Silents (71%) also have cell phones.21 Compared with older adults, Millennials and Gen Xers have somewhat different standards about when and where cell phones should be used. Overall, the public has a fairly stringent view of when it’s appropriate for people to use their cell phones to send or receive messages or go on the internet. The vast majority of adults say it is not okay to use a cell phone at church or worship service (89%), during a class or lecture (82%) or during a business meeting (81%). About seven-in-ten (72%) say it’s not okay to use a cell phone at a family dinner.

Millennials and Gen Xers are more lenient about cell phone use at the dinner table than are their older counterparts. Roughly three-in-ten say it’s okay to use a cell phone under these circumstances, only one-in-five Boomers and Silents agree.

Millennials are more likely than any other generation to say it is okay to use a cell phone during a class or lecture. Some 22% of Millennials say this, compared with 16% of Gen Xers, 12% of Boomers and just 5% of Silents.

Boomers and Silents are nearly universally opposed to the idea of using cell phones at religious services, and Silents are the least likely to approve of using cell phones during business meetings.