Global Patterns and Shifts

The shifts in migration by country income categories are to some extent associated with geographic changes in migrant destinations. Sometimes called the Global North, countries such as Canada and the United States in North America (among others including Australia and several countries in Europe) contain a greater share of international migrants today than a quarter century ago.3 At the same time, a larger share of international migrants now live in the Middle East-North Africa region. (For more information about which countries are part of which regions, see Appendix A: Methodology.)

The shifts in migration by country income categories are to some extent associated with geographic changes in migrant destinations. Sometimes called the Global North, countries such as Canada and the United States in North America (among others including Australia and several countries in Europe) contain a greater share of international migrants today than a quarter century ago.3 At the same time, a larger share of international migrants now live in the Middle East-North Africa region. (For more information about which countries are part of which regions, see Appendix A: Methodology.)

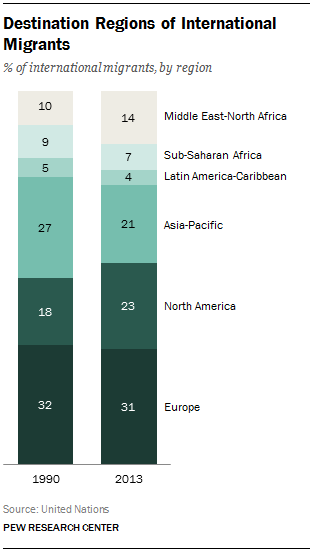

In 1990, the largest share of international migrants (32%) lived in Europe. This group of international migrants consisted mainly of migrants born in developing countries beyond Europe (such as Turkey, Algeria and Pakistan), but also migrants who had moved between European countries (such as Eastern Europeans living in Western Europe).

Meanwhile, about a quarter (27%) of international migrants in 1990 lived in the Asia-Pacific region. This group of migrants mainly consisted of cross-border migrants, who for a variety of reasons (economic opportunities, military conflicts, family reunification) lived in nearby countries within the Asia-Pacific region.

Nearly a fifth (18%) of international migrants in 1990 lived in North America, mostly in the United States. Smaller shares of migrants lived in the Middle East-North Africa (10%), sub-Saharan Africa (9%) and Latin America-Caribbean (5%) regions.

But a global shift in the destinations of migrants began in the 1990s. A greater number of people born in countries such as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh in the Asia-Pacific region started moving to the oil-rich countries of the Persian Gulf in the Middle East-North Africa region, shrinking the share of Asian migrants who may have otherwise moved to other countries in the Asia-Pacific or other regions.

Joining these Asian migrants in the Middle East were migrants from Europe and North America. Together, this migration to the Middle East-North Africa region increased the share of international migrants there from 10% in 1990 to 14% in 2013.

At the same time, huge numbers of migrants, many of whom were born in Latin American and Caribbean countries, crossed into the United States during the past quarter century. Combined with increased migration to Canada, this large-scale movement led to a growing share of international migrants living in North America, climbing from 18% of international migrants in 1990 to 23% in 2013.

Although the share of international migrants in Europe stayed about the same between 1990 and 2013, the composition of migrants living in Europe changed considerably. One reason was that migrants of previous waves, mostly among European countries, started to die off or returned to their countries of birth. Among their replacements were considerable numbers of people from developing countries in North Africa (such as Morocco and Algeria), Asia (such as Turkey and India) and refugee-sending countries in the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa (such as Iraq and Somalia).

Changes in Top Destination Countries

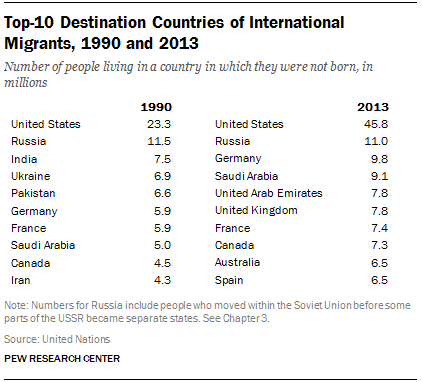

In light of these regional and economic shifts, several countries received a much higher number of migrants than other destinations. And the list of top destination countries has changed between 1990 and 2013.

With a large number of migrants moving northward from Latin America and the Caribbean, the U.S. became an even larger destination of the world’s migrants, numbering 23 million in 1990 but ballooning to 46 million in 2013.

In addition, millions of people who had moved within their own countries suddenly were redefined as international migrants when their national borders changed. For example, in 1990, millions of people living in former USSR countries—including more than 10 million in Russia and more than 6 million in Ukraine—became “migrants” almost overnight. Their migrant status changed to “foreign born” when new borders separating the former USSR states were established. These “migrants” found themselves on the opposite side of a border they had crossed years earlier, but at the time their migration was not considered an international move. Many of these “migrants” moved back to their homelands, but many continued to remain in their current countries of residence. Also, Russia’s economic growth attracted more migrants from neighboring countries, sustaining its total number of immigrants around 11 million in 2013.

In addition, millions of people who had moved within their own countries suddenly were redefined as international migrants when their national borders changed. For example, in 1990, millions of people living in former USSR countries—including more than 10 million in Russia and more than 6 million in Ukraine—became “migrants” almost overnight. Their migrant status changed to “foreign born” when new borders separating the former USSR states were established. These “migrants” found themselves on the opposite side of a border they had crossed years earlier, but at the time their migration was not considered an international move. Many of these “migrants” moved back to their homelands, but many continued to remain in their current countries of residence. Also, Russia’s economic growth attracted more migrants from neighboring countries, sustaining its total number of immigrants around 11 million in 2013.

Migration among countries within the Indian subcontinent is common. In 1990, about 7 million migrants lived in India as well as in Pakistan. Some of these migrants didn’t actually move as international migrants, but like the Russian situation, became “migrants” because of changing borders in previous decades. But the long-term effects of this earlier “migration” dropped off by 2013, leading India and Pakistan to no longer rank in the world’s top-10 destinations.

Many countries in Europe as well as Canada and Australia and other traditional destinations continued to receive migrants during the past quarter century. For example, Germany’s growing ranks of foreign-born persons from nearly 6 million immigrants in 1990 to nearly 10 million immigrants in 2013 included many migrants from countries formerly aligned with the Soviet bloc as well as increased migration from Turkey and the Balkans. With growing tourism and agricultural business in Spain, many Moroccans and Romanians moved to Spain, helping to bolster its immigrant population to over 6 million.

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia (9 million foreigners) and the United Arab Emirates (7.8 million foreigners) became even more prominent destination countries by 2013. With millions of temporary migrants to support the growing oil industry and related infrastructure in these countries, Gulf Cooperation Council countries have become important hubs for migrants in recent years.

Top Destinations by Percent Foreign born

Destinations can be ranked by the number of international migrants within their borders. But differences between immigrants and non-immigrants living within their borders can also be compared.

Destinations can be ranked by the number of international migrants within their borders. But differences between immigrants and non-immigrants living within their borders can also be compared.

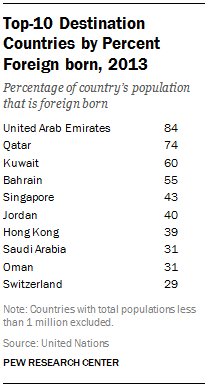

For example, several countries in the Persian Gulf region (such as the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait and Bahrain) are majority foreign born, while other countries in the region (such as Saudi Arabia and Oman) are nearly a third foreign born.

And some countries with the highest percentage of immigrants are some of the geographically smallest countries. For example, about 4 in 10 people living in Hong Kong and Singapore were not born there.

Some destination countries have received a large number of refugees from neighboring countries, vastly increasing the share of their population that is foreign born. For example, about 4 in 10 people in Jordan are estimated to be foreign born, many of whom have come from neighboring Palestinian Territories, Iraq and Syria, often as refugees.

Several Western countries have become important migrant destinations because of their economic growth and high employment opportunities. Although these countries do not have the highest percentages of foreign-born residents, some Western countries have a greater share of immigrants than others. For example, Australia, New Zealand and Canada all have foreign-born percentages exceeding 20%. Several European countries such as Ireland, Sweden and Austria are also about 15% foreign-born. Finally, around 14% of people living in the United States in 2013 were born outside of the U.S., compared with 9% in 1990.

Interactive Remittance Flows Worldwide in 2015

Interactive Remittance Flows Worldwide in 2015