The gender gap may open wide on many issues, but the new Pew Research Center survey finds that men and women generally agree about what they value in a job.

The gender gap may open wide on many issues, but the new Pew Research Center survey finds that men and women generally agree about what they value in a job.

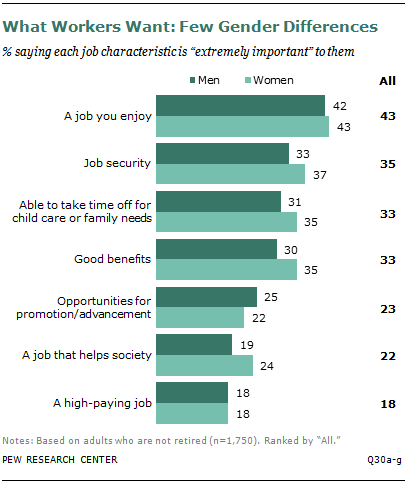

Overall, Americans give their highest priority to having a job they enjoy doing (43% say this is “extremely important” to them). About a third of all adults consider job security, the ability to take time for family needs and good benefits to be equally valuable.

Falling lower on the list of the public’s priorities are opportunities for advancement (23%), a job that helps society (22%) and high pay (18%).

Most of these judgments differ little by gender, the survey found. For example, about four-in-ten men and women say it is “extremely important” to them to have a job that they enjoy. Equal shares of men and women (18%) rate a high-paying job as a top priority.

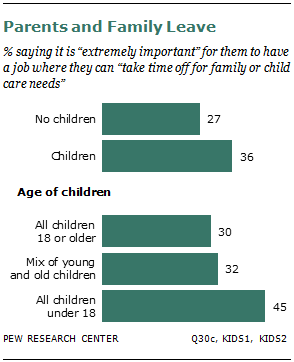

Differences between demographic groups emerge when the analysis shifts away from gender. Parents of young children are more likely than other adults to rate family leave time as a job essential (45% vs. 28%). And members of the Millennial generation are significantly more likely than other adults to rank a job they enjoy as extremely important to them (50% for Millennials vs. 40% for older adults).

On other questions in the survey, differences by demographic group loom even larger. For example, men, minorities and Millennials are more likely than women, whites and other generations to say they would someday like to be a boss or top manager at work. Men also are more likely than women to say they have ever asked for a raise or promotion at work.

Gender and Jobs

To measure what men and women value in a job, the survey asked respondents to rate how important seven job attributes are to them on a four-point scale ranging from “extremely important” to “not too important.”

The characteristics tested in the poll were: “having a job you enjoy doing,” “having job security,” “being able to take time off for family or child care needs,” “having a job that offers good benefits,” “having opportunities for promotion or advancement,” “having a job that helps society” and “having a high-paying job.”

The survey found that men and women value the same job characteristics in virtually equal proportions. For example, 42% of men and 43% of women say having a job they enjoy doing is extremely important to them.

A somewhat smaller share of men (33%) and women (37%) rank job security as a top job priority. About as many say having the opportunity to take time off from work to deal with child or family needs is extremely important (31% for men vs. 35% for women). Roughly similar shares of men (30%) and women (35%) rank good benefits as a critical factor for them when evaluating a job.

Men and women also agree about the job characteristics that are comparatively less important. Similar shares of men and women rank as extremely important a job that offers opportunities to advance (25% for men, 22% for women) or that pays well (18% for both sexes).

These gender similarities span the generations. For example, about half of Millennial men (48%) and women (52%) say that having a job they enjoy doing is extremely important to them. That view is shared by 42% of Gen X men and about as many Gen X women (45%). Among Baby Boomers, the proportions also are similar (36% for men and 40% for women).

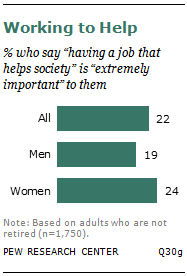

Men and women differ on one job characteristic. Women are more likely than men to say that having a job that helps society is extremely important to them (24% vs. 19%). This gap swells to 13 percentage points when the analysis is expanded to include those who say they rate this attribute as “very important” (72% vs. 59%).

Men and women differ on one job characteristic. Women are more likely than men to say that having a job that helps society is extremely important to them (24% vs. 19%). This gap swells to 13 percentage points when the analysis is expanded to include those who say they rate this attribute as “very important” (72% vs. 59%).

Millennial women are particularly more likely than men regardless of generation to say a job that helps society is extremely important to them (29% for Millennial women vs. 19% for Millennial and Gen X men and 17% for Boomer men).

What the Generations Value in a Job

The generations differ significantly about what is most important to them in a job. In most instances, these differences in attitudes appear to be due to family and work circumstances related to age.

The generations differ significantly about what is most important to them in a job. In most instances, these differences in attitudes appear to be due to family and work circumstances related to age.

Reflecting their place in the first decades of their working lives, Millennials and Gen Xers more highly value opportunities for advancement on the job than Baby Boomers who are at or near the peak of their careers (27% for Millennials and 30% for Gen Xers vs. 15% for Boomers).

Millennials also are more likely than Boomers to say job security is “extremely important” to them (40% vs. 31%).

Values related to family and children rank higher with Millennials and Gen Xers, the generations who are at the time of life when most people marry and start raising a family. For example, Millennials and Gen Xers place a higher value on jobs that offer them time off to deal with child care or family issues (36% and 39%, respectively, vs. 26% for Baby Boomers).

No clear generational differences emerge on the value of good job benefits, an attribute that 34% of Millennials, 36% of Gen Xers and 31% of Boomers say is “extremely important” to them.

Similarly, the three generations are about equally likely to place a low value on a job that pays well. According to the survey, about 19% of Millennials, 22% of Gen Xers and 17% of Boomers say a job that comes with a big paycheck is “extremely important” to them.

A more nuanced picture emerges when those who say a high-paying job is “very important” to them are analyzed with adults who rate high pay as very important. Gen Xers are now significantly more likely than younger and older adults to say that a high-paying job is “extremely” or “very important” (62% of Gen Xers, compared with 52% of Millennials and 53% of Boomers).

Other generational differences may not be as closely tied to differences in family status or employment. For example, Millennials stand out in the importance they place on having a job that they enjoy doing. About half (50%) of these young adults born after 1980 say doing work they enjoy is “extremely important” to them, compared with 38% of Baby Boomers who feel the same way.31

What Working Parents Value in a Job

As every parent knows, young children change your life. The Pew Research survey suggests they may also change what mothers and fathers value highly in a job. According to the survey, parents with children younger than 18 place a higher priority than other adults on family-friendly work conditions and, more broadly, on jobs that offer good benefits.

As every parent knows, young children change your life. The Pew Research survey suggests they may also change what mothers and fathers value highly in a job. According to the survey, parents with children younger than 18 place a higher priority than other adults on family-friendly work conditions and, more broadly, on jobs that offer good benefits.

Overall, about four-in-ten (41%) of all parents with children younger than 18 say it is “extremely important” to them to have a job that allows them to take time off for child care and family issues. In contrast, only about a quarter of adults who do not have children (27%) value family leave as highly. For adults with children ages 18 and older or a mix of young and grown children, about three-in-ten say family leave is extremely important to them (30% and 32%, respectively).

Similarly, about four-in-ten (37%) of all parents with younger children but 28% of all childless adults rank good benefits as a top job attribute for them. Adults with older children or a mix of younger and grown children (33% and 32%) appear to fall between childless adults and those who have only younger children, though the differences between these groups are not statistically significant.

Being the Boss

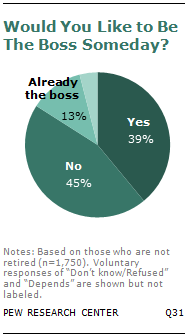

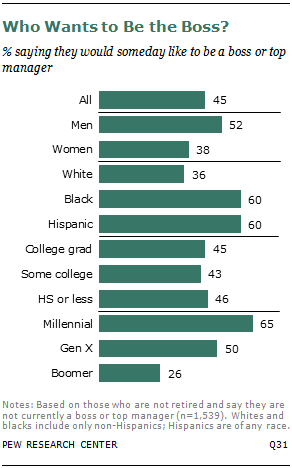

About four-in-ten Americans who are not yet retired say they someday want to be the boss or a top manager—and another 13% say they already are.

About four-in-ten Americans who are not yet retired say they someday want to be the boss or a top manager—and another 13% say they already are.

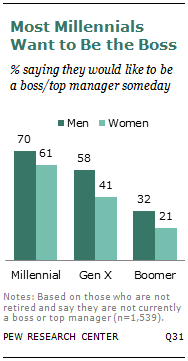

Among those who are not currently a boss or top manager,32 Millennials, men and minorities are more likely than non-Millennials, women and whites to say they aspire to eventually fill a top position at work.

Perhaps because so many Millennials are comparatively recent entrants into the workforce, they are easily the most ambitious generation. About two-thirds (65%) of these young adults say they want to be the boss or a top executive someday. In contrast, half (50%) of all Gen Xers and 26% of Boomers share this goal.

Perhaps because so many Millennials are comparatively recent entrants into the workforce, they are easily the most ambitious generation. About two-thirds (65%) of these young adults say they want to be the boss or a top executive someday. In contrast, half (50%) of all Gen Xers and 26% of Boomers share this goal.

Millennial men are somewhat more likely than Millennial women to say they someday want to be the boss (70% vs. 61%). The gender gap is wider among Gen Xers: About six-in-ten Gen X men (58%) but 41% of Gen X women aspire to a corner office, while for Baby Boomers the dream of being the boss has mostly faded for both men (32%) and women (21%).

A similar pattern emerges when children are factored into the analysis. Overall, fathers are still more likely than mothers to seek a top executive job, regardless of whether they have children under the age of 18.

For example, about six-in-ten (59%) fathers with young children want to be the boss, compared with about half (48%) of mothers. Similarly, about half (49%) of men with no younger children would like to be a boss or top manager, compared with 32% of women without younger children.

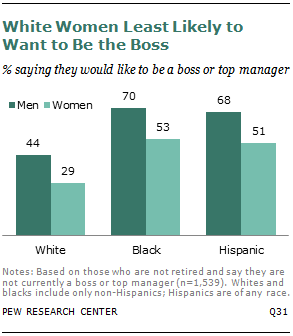

Race, Gender and Being the Boss

According to the survey, minorities are far more likely than whites to say they someday would like to be the boss. Equal proportions of blacks and Hispanics (60%) express the desire to someday become a top manager, compared with 36% of whites.

According to the survey, minorities are far more likely than whites to say they someday would like to be the boss. Equal proportions of blacks and Hispanics (60%) express the desire to someday become a top manager, compared with 36% of whites.

These differences narrow but do not disappear when the results are further broken down by gender. Among men, about seven-in-ten blacks (70%) and Hispanics (68%) say they would like to be the boss, compared with 44% of white men. About half of all black women (53%) and Latinas (51%) want to be a workplace leader, while only 29% of white women—the smallest share of any group—harbor a similar goal.

These differences narrow but do not disappear when the results are further broken down by gender. Among men, about seven-in-ten blacks (70%) and Hispanics (68%) say they would like to be the boss, compared with 44% of white men. About half of all black women (53%) and Latinas (51%) want to be a workplace leader, while only 29% of white women—the smallest share of any group—harbor a similar goal.

The Bosses

So who is the boss? In terms of gender, the boss looks very much like those who aspire to a top job in the workplace. Men are more likely than women to say they already are the boss (16% vs. 10%).33 But in other key ways, America’s bosses are the demographic mirror opposite of those who have ambitions to replace them at the top of the workplace ladder.

So who is the boss? In terms of gender, the boss looks very much like those who aspire to a top job in the workplace. Men are more likely than women to say they already are the boss (16% vs. 10%).33 But in other key ways, America’s bosses are the demographic mirror opposite of those who have ambitions to replace them at the top of the workplace ladder.

As shown earlier, whites who are not the boss express less desire than minorities to someday be the boss. But whites still dominate in the corporate suite: 16% of all whites are bosses, compared with 6% of blacks and 4% of Hispanics, the survey found.

And perhaps predictably, the Millennial generation, recently arrived in the workforce with an abundance of ambition, will have to wait a few more years to break into the executive suite. Only 4% of Millennials say they are bosses, compared with 16% of Gen Xers and 17% of Baby Boomers.

The survey also found that the path to a corner office runs through a college campus. According to the survey, those with college degrees (16%) or some college experience (15%) are most likely to say they are now a boss or top manager.

In contrast, only 8% of all high school graduates and those with less education have a top job where they work.

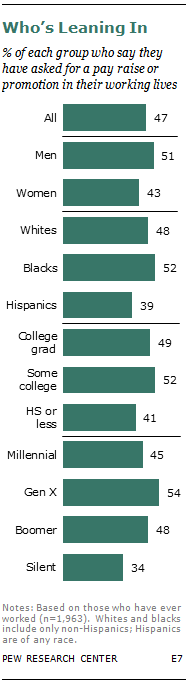

Leaning In

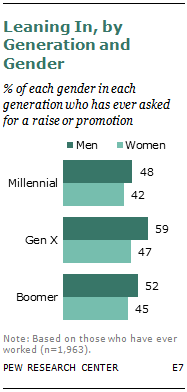

About half (47%) of all adults who have ever been employed say they have asked for a raise or promotion at some point in their working lives—roughly half of all men (51%) and a smaller share of women (43%).

About half (47%) of all adults who have ever been employed say they have asked for a raise or promotion at some point in their working lives—roughly half of all men (51%) and a smaller share of women (43%).

According to the survey, blacks and whites are significantly more likely to have pressed their employers for a raise or promotion than Hispanics (48% among whites and 52% among blacks vs. 39% for Hispanics).

A generational analysis reveals one striking result: The generation that has been in the workforce the longest is the least likely to have ever requested a raise or promotion. Only about a third of members of the Silent generation (34%) have asked to advance. That’s even smaller than the share of Millennials (45%), the adults who have been in the workforce the least amount of time. About half (54%) of Gen Xers and 48% of Baby Boomers say they have asked for a salary hike or promotion at some point in their careers.

When gender is factored into the analysis, an even more nuanced picture emerges. Among Millennials, roughly similar shares of men (48%) and women (42%) have sought to improve their pay or position. About half (52%) of Boomer men and 45% of women have done the same.

But among Generation X, men are significantly more likely than women to have sought to advance. According to the survey, about six-in-ten Gen X men (59%) have asked for a pay raise or promotion, compared with 47% of Gen X women.

In fact, Gen X men are significantly more likely than Millennial men (48%) or women of any generation to have sought a raise or promotion. (The samples of men in the Silent generation are too small to analyze.)

In fact, Gen X men are significantly more likely than Millennial men (48%) or women of any generation to have sought a raise or promotion. (The samples of men in the Silent generation are too small to analyze.)

Among women who have ever been employed, roughly equal shares of Millennials (42%), Gen Xers (47%) and Boomers (45%) have ever asked for a better job or higher salary. Gen X and Boomer women also are different than women in the Silent generation (33%).

One caution is in order when interpreting these results. Age and length of time in the workforce may confound these findings. It might be reasonable to expect those who worked for more years would have more opportunities to ask for raises and promotions.

That means generational comparisons should be made cautiously. Millennials, as a group, have not worked as many years as Gen Xers, who in turn have not been in labor force as long as Boomers or Silents. It is possible that today’s Millennials are far more aggressive about asking for raises or promotions than Boomers or Silents were at a comparable age.

In light of this, what may be most remarkable about these results is the low levels of “leaning in” among adults aged 66 and older. Among those who have ever worked, only about a third—34%—say they have ever asked for a raise or promotion, while nearly half or more of all other generations report that they have done this. For these older adults, the label of “Silent generation” seems particularly appropriate.

Video Thereu2019s more to the story of the shrinking pay gap

Video Thereu2019s more to the story of the shrinking pay gap