Five decades after Martin Luther King Jr.’s historic “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington, D.C., racial equality remains an elusive goal. Fewer than half of all Americans say the country has made “a lot” of progress in the past 50 years toward achieving King’s vision of racial equality. At the same time about half also say that much remains to be done.

Five decades after Martin Luther King Jr.’s historic “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington, D.C., racial equality remains an elusive goal. Fewer than half of all Americans say the country has made “a lot” of progress in the past 50 years toward achieving King’s vision of racial equality. At the same time about half also say that much remains to be done.

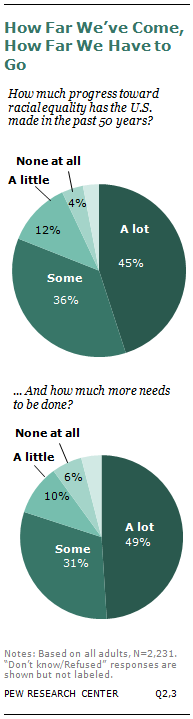

A new Pew Research Center survey finds that 45% of the public says the country has made a lot of progress in the past 50 years toward racial equality. An additional 36% say “some” improvement has been made, while about one-in-six Americans (15%) say they have seen little or no change.

Yet the overwhelming majority says the slow and sometimes painful process of building a color-blind society remains largely unfinished business. About half of all Americans (49%) say the country still needs to make “a lot” more progress to become a truly color-blind society. Three-in-ten (31%) say some progress still needs to be made. Only a relatively small share (16%) say little or nothing remains to be done.

Echoing the social fractures of the civil rights era, the survey finds the country remains deeply divided by race and by political partisanship over what has been accomplished and what still needs to be done to achieve racial equality.

Turning to other topics, the survey finds that blacks are consistently more likely than whites to say blacks are treated less fairly in their communities by institutions such as the criminal justice system, the public schools, at their place of employment and when voting in elections.

According to the survey, seven-in-ten blacks say African Americans are treated less fairly than whites in their dealings with police. In contrast, some 37% of whites say blacks are treated less fairly, and 13% are unsure.

Similarly, about seven-in-ten blacks (68%) say African Americans are not treated as fairly as whites by the courts. About a quarter of whites (27%) agree with this assessment, and 16% are unsure.

On the issue of group relations, the survey finds that a majority of whites, blacks and Hispanics say the races generally get along well with each other.

On the issue of group relations, the survey finds that a majority of whites, blacks and Hispanics say the races generally get along well with each other.

While perceptions of relations between blacks and whites remain unchanged since they were last measured in a 2009 Pew Research Center survey, a growing share of the public says blacks and Hispanics as well as Hispanics and whites are getting along better today than they did four years ago.

The results also suggest that relations between blacks and Hispanics are viewed as being somewhat less positive than those between whites and blacks or whites and Hispanics.

Demographic Differences

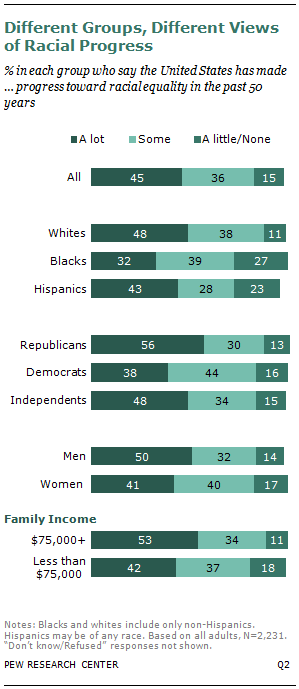

Blacks and whites hold different perceptions of the progress the country has made toward King’s dream of racial equality.

According to the survey, about half of all whites (48%) but only a third of blacks (32%) say “a lot” of progress has been made in the past 50 years to achieve equality between the races.

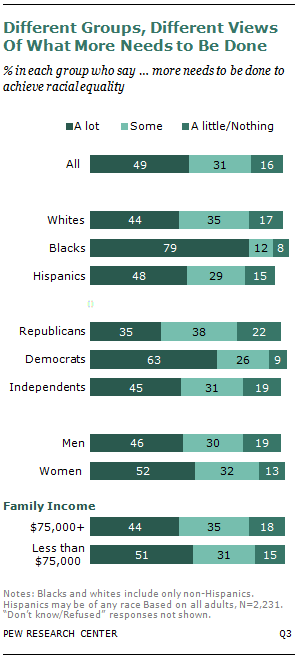

The racial divide opens even wider when respondents are asked about how much still needs to be done to achieve King’s dream of racial parity. About eight-in-ten blacks (79%) say a lot still needs to be done—more than 30 percentage points greater than the proportion of whites (44%) who feel the same way.

While the political environment is arguably less racially charged now than it was in 1964 when King delivered his “Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, the survey finds that Republicans and Democrats hold very different views on the extent of racial progress and the need for more.

While the political environment is arguably less racially charged now than it was in 1964 when King delivered his “Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, the survey finds that Republicans and Democrats hold very different views on the extent of racial progress and the need for more.

A majority of Republicans (56%) but 38% of Democrats say the country has made a great deal of progress insuring racial equality, a view that is also shared by 48% of all political independents.

When respondents are asked how much needs to be done in the future, about a third of Republicans (35%) say “a lot” still needs to be done, compared with 63% of Democrats. Among independents, about 45% say much remains unfinished.

These partisan differences remain large when just the views of white Democrats and Republicans are compared. Among whites, about six-in-ten Republicans (58%) but 40% of Democrats say significant progress has been made toward racial equality. And fully 56% of white Democrats but only a third (34%) of white Republicans say a lot more progress needs to be made.

Gender, Education and Income

Smaller differences emerge among other key demographic groups. For example, men are somewhat more likely than women to say the country has made significant progress toward equality in the past 50 years (50% vs. 41%). They also are less likely than women to say that significantly more progress needs to be made (46% vs. 52%).

Smaller differences emerge among other key demographic groups. For example, men are somewhat more likely than women to say the country has made significant progress toward equality in the past 50 years (50% vs. 41%). They also are less likely than women to say that significantly more progress needs to be made (46% vs. 52%).

Blacks who attended some college or more are significantly less likely than those with less formal education to say the country has made major strides eliminating racial bias in the past five decades (26% vs. 38%). But about eight-in-ten in both groups say that much more progress is needed. Among whites there is no significant difference.

The survey also finds that those with annual family incomes of $75,000 or more are more likely than those with incomes below $75,000 to say a lot of progress has been made on racial equality (53% vs. 42%). These higher earners also are less likely than those earning less than $75,000 to believe that much more progress needs to be made (44% vs. 51%).

Most Say More Progress Needed

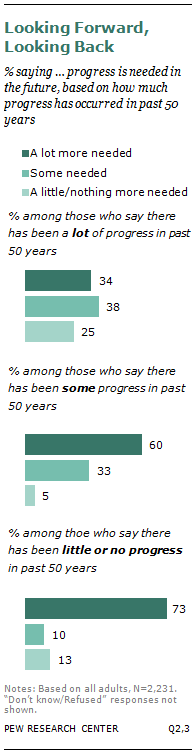

Irrespective of how far they think the country has come toward achieving racial equality, eight-in-ten Americans say “a lot” or “some” additional improvement is needed to accomplish that goal.

Even among the 45% of the country that believes much already has been done, about a third (34%) say a lot more progress is needed.

That proportion rises to 60% among those who say some progress has been made and climbs to 73% among those who say only a little or no change has occurred.

Only about one-in-eight (13%) of those who see little or no progress in the past 50 years also say little or nothing still needs to be done.

How Groups Are Getting Along

While relations between blacks, whites and Hispanics are not perfect, majorities of each group say they get along reasonably well.

While relations between blacks, whites and Hispanics are not perfect, majorities of each group say they get along reasonably well.

About three-quarters of respondents think blacks and whites get along “very well” (13%) or “pretty well” (63%), according to the survey. Whites are somewhat more likely than blacks or Hispanics to say blacks and whites get along well (81% among whites vs. 73% among blacks and 60% among Hispanics).

About three-quarters of whites (77%) also say their group and Hispanics get along very well or fairly well, a view shared by a roughly equal share of Hispanics (74%). About two-thirds of all blacks (64%) also say the groups get along, though 12% say they do not know.

A small majority of Americans (54%) say blacks and Hispanics get along well, in part because one-in-six respondents—including 22% of whites—told interviewers they do not know enough about black-Hispanic relations to answer the question. Among blacks, about

eight-in-ten (78%) say the two groups get along well, a view echoed by 61% of Hispanics.

The survey suggests that overall perceptions of relations between blacks and whites have not changed since the question was last asked in a Pew Research Center survey conducted in November 2009. About three-quarters of all respondents in both surveys said that blacks and whites get along either

very or pretty well.

At the same time, views on the relations between Hispanics and the two races have improved in recent years. Asked how well whites and Hispanics get along, the proportion saying these groups got along very or pretty well increased from 67% in 2009 to 74% in the latest survey. At the same time, the proportion who say blacks and Hispanics got along well rose from 48% to 54%.

Treatment of Blacks by the Courts, Police Seen as Less Fair

From the courtroom to the classroom to the voting booth, blacks are consistently more likely than whites to say blacks in their community are treated less fairly by key institutions, according to the Pew Research Center survey.

From the courtroom to the classroom to the voting booth, blacks are consistently more likely than whites to say blacks in their community are treated less fairly by key institutions, according to the Pew Research Center survey.

Blacks are most likely to perceive unequal treatment by the court system and in their dealings with the police, the survey finds. And these are the two areas where sizable minorities of whites also see inequity. Nonetheless, there are still significant racial gaps.

According to the survey, seven-in-ten blacks say African Americans are treated less fairly than whites in their dealings with police. Some 37% of whites say blacks are treated less fairly in this realm and an additional 13% say they do not know.

Similarly, about seven-in-ten blacks (68%) say African Americans are not treated as fairly as whites by the courts. Roughly one-in-four whites (27%) agree with this assessment, and 16% of whites are unsure.

The racial gap persists when the focus turns to other types of local organizations. Some 54% of all blacks say blacks are not treated as fairly as whites on the job or at work. Among whites, only 16% express this view and an additional 12% have no opinion.

Roughly half of all blacks (51%) say public schools in their area treat blacks less fairly than whites; 15% of whites agree that that is the case. (Some 12% of blacks and whites said they do not know how blacks were treated in the schools.)

Roughly half of all blacks (51%) say public schools in their area treat blacks less fairly than whites; 15% of whites agree that that is the case. (Some 12% of blacks and whites said they do not know how blacks were treated in the schools.)

Blacks also are more likely than whites to say that black people are treated less fairly while getting health care (47% vs. 14%), in stores and restaurants (44% vs. 16%), and when they vote in local elections (48% vs. 13%).

Hispanics, while less likely than blacks to say blacks are treated less fairly, are more likely than whites to perceive unequal treatment of blacks. About half (51%) of Hispanics say blacks are treated unfairly in interactions with the police, with substantial minorities perceiving unfair treatment in other areas.

Younger people are more likely than others to say blacks are treated less fairly than whites in many of these areas. For example, while about half of those ages 18-29 (53%) say blacks are treated less fairly than whites by the police, that compares with only about a third (36%) of adults ages 65 and older. Some of the difference in perceptions about fair treatment may be attributable to racial composition, as younger Americans are more likely to be non-white than older Americans. But age differences on these questions are also apparent among whites (49% of whites ages 18 to 29 say blacks are treated less fairly by the police, 32% of older whites say this).

Across-the-board, Democrats are more likely than Republicans or independents to say blacks in their community are treated less fairly than whites. Although 57% of Democrats say this about the police, that share drops to 43% of independents and just 29% of Republicans.

The perception that voting in elections is less fair for African Americans than whites—a political point of contention in recent months—also divides along partisan lines. While just 20% of the overall public says blacks are treated less fairly than whites when voting in elections, that rises to about a third of Democrats (32%), compared with only about one-in-ten Republicans (11%).

Although blacks (and other minorities) make up a larger share of Democrats than Republicans, the pattern of partisan differences on these questions persists even when controlling for race: White Democrats are significantly more likely than white Republicans to say blacks are treated less fairly in each of these areas.

Personal Experiences of Discrimination

About a third (35%) of African Americans say they have personally experienced discrimination or been treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity over the past year. That compares with 20% of Hispanics and 10% of whites.

About a third (35%) of African Americans say they have personally experienced discrimination or been treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity over the past year. That compares with 20% of Hispanics and 10% of whites.

Personal experiences with discrimination are associated with perceptions of unfair treatment. Blacks who have experienced discrimination over the past 12 months are more likely than others to say blacks are treated less fairly by local community institutions.

Blacks who have faced discrimination in the past year also are less likely than other blacks to say “a lot” of progress has been made toward racial equality (23% vs. 37%) and are significantly more likely to believe a lot more progress is necessary (87% vs. 74%).

Interactive Tracking 50 Years of Demographic Trends

Interactive Tracking 50 Years of Demographic Trends