Despite the Great Recession and the sluggish recovery that followed, young adults remain extremely confident about their financial future. While a large majority of those ages 18 to 34 (whether they are employed or not) say they do not currently have enough money to lead the kind of life they want, most believe they will eventually attain that goal.

Despite the Great Recession and the sluggish recovery that followed, young adults remain extremely confident about their financial future. While a large majority of those ages 18 to 34 (whether they are employed or not) say they do not currently have enough money to lead the kind of life they want, most believe they will eventually attain that goal.

According to the new Pew Research survey, only 31% of all young adults say they now have enough income to lead the kind of life they want. However, an additional 57% say that while they don’t have enough money now, they think they will in the future. Only one-in-ten (9%) say they don’t have enough now to lead the kind of life they want and don’t believe they ever will.22

Middle-aged and older adults are more satisfied than young adults with the resources they have now. But the share that is pessimistic about their financial future is three times as high among the older age groups. Nearly half of those ages 35 to 64—prime earning years—say they currently have enough income to lead the kind of life they want. While 22% say they don’t have enough now but believe they will in the future, fully 27% say they don’t have enough now and don’t think they will in the future.23

Among adults 65 and older, most of whom are no longer working, 61% say they have enough income now to lead the kind of life they want. For those who say they don’t currently have enough income, the vast majority don’t anticipate this changing in the future: 29% say they don’t have enough money now and they won’t in the future. Only 3% say they think they will have enough money in the future.

While the recession affected many dimensions of economic life—wages, retirement savings, home values, debt—public attitudes about future earning potential have remained remarkably stable. A 2004 Pew Research survey asked the same series of questions of both employed and unemployed adults: Did they earn enough money or have enough income to lead the kind of life they wanted, and, if not, did they think they would be able to earn enough money in the future?

While the recession affected many dimensions of economic life—wages, retirement savings, home values, debt—public attitudes about future earning potential have remained remarkably stable. A 2004 Pew Research survey asked the same series of questions of both employed and unemployed adults: Did they earn enough money or have enough income to lead the kind of life they wanted, and, if not, did they think they would be able to earn enough money in the future?

Overall, young adults were more satisfied with their earnings or income in 2004 than they are today (41% said they had enough income to lead the kind of life they wanted versus 31% now). This is not surprising, given the significant falloff in jobholding among the youngest adults. Still, for the majority who did not have enough income in 2004, most said they expected to have enough in the future. Only 10% said they didn’t think they ever would (compared with 9% now).

Roughly half of those ages 35 to 64 (51%) said they had enough income in 2004. Among those who said they didn’t have enough, the balance of opinion about the future was more negative than positive. And, just as is the case today, a solid majority of older adults said they had enough income to lead the kind of life they wanted. Three-in-ten said they did not have enough income or earn enough money, and most in that group didn’t think their situation would improve.

The consistent trend in opinion, in spite of the turbulent economic conditions during the intervening years, suggests that optimism is related more to the stage of life than to the dynamics of the national economy.

Optimism in Spite of Frustration with Earnings, Income

While the share of young adults who are employed has fallen sharply in recent years, the way in which working young adults view their earnings has changed very little. In 1996, at a time when the national economy was thriving and many more young adults were employed, 66% of 18- to 34-year-olds who were working at least part time said they did not earn enough money to lead the kind of life they wanted.24 In 2011, roughly the same proportion (62%) said they didn’t earn enough.

While the share of young adults who are employed has fallen sharply in recent years, the way in which working young adults view their earnings has changed very little. In 1996, at a time when the national economy was thriving and many more young adults were employed, 66% of 18- to 34-year-olds who were working at least part time said they did not earn enough money to lead the kind of life they wanted.24 In 2011, roughly the same proportion (62%) said they didn’t earn enough.

The gap between young workers and middle-aged and older workers has remained stable over this period. In 1996, 48% of workers ages 35 and older said they did not earn enough to lead the kind of life they wanted. In 2011, an identical share said the same.

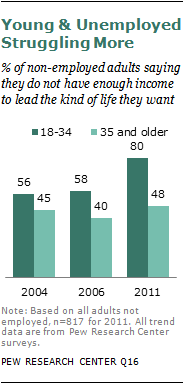

The situation is much different for young adults who are not employed. In 2004, 56% of those ages 18 to 34 who were not employed said they did not have enough income to lead the kind of life they wanted. By 2011, 80% of this group reported that they did not have enough income to lead the kind of life they wanted—an increase of 24 percentage points from 2004.

The situation is much different for young adults who are not employed. In 2004, 56% of those ages 18 to 34 who were not employed said they did not have enough income to lead the kind of life they wanted. By 2011, 80% of this group reported that they did not have enough income to lead the kind of life they wanted—an increase of 24 percentage points from 2004.

Over that same period, the share of non-working adults ages 35 and older who said they did not have enough income increased only slightly, from 45% to 48%. As a result, the gap between young non-employed adults and their older counterparts increased significantly.

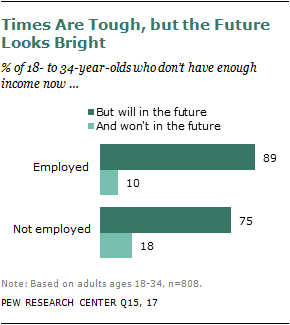

The good news is that for both working and non-working young adults, frustration with current earnings and income has not dampened their optimism about the future. Among those ages 18 to 34 who are employed and say they are not currently earning enough to lead the kind of life they want, fully 89% say they believe they will earn enough in the future.

Young adults who are not working are nearly as optimistic—75% of those who say they don’t have enough income to lead the kind of life they want believe they will have enough money in the future. Less than one-in-five (18%) expect that they won’t have enough.

Young adults who are not working are nearly as optimistic—75% of those who say they don’t have enough income to lead the kind of life they want believe they will have enough money in the future. Less than one-in-five (18%) expect that they won’t have enough.

Older adults are not nearly as upbeat about their future prospects. Among those ages 35 and older who are employed and are not currently making enough to lead the kind of life they want, less than half (48%) expect they will earn enough in the future. For those ages 35 and older who are not currently working, only 21% say the same.

Young Adults’ Optimism Extends Far into the Future

Not only are young people optimistic about their own financial futures, but they also are confident that their children will be better off financially than they are now. In contrast, older people are significantly less optimistic that their children will fare better financially than they have. According to the survey, six-in-ten adults ages 18 to 34 expect their children to be doing better financially when they reach a comparable age, versus 43% of those 35 and older.

Not only are young people optimistic about their own financial futures, but they also are confident that their children will be better off financially than they are now. In contrast, older people are significantly less optimistic that their children will fare better financially than they have. According to the survey, six-in-ten adults ages 18 to 34 expect their children to be doing better financially when they reach a comparable age, versus 43% of those 35 and older.

However, these data also suggest that views begin to change around the time a young person turns 30. Among those 18 to 29 years old, about two-thirds (65%) are optimistic about their children’s financial future. But among those just slightly older, 30 to 34, less than half (46%) are as hopeful.

These views of young people also vary by demographic group. Young women are significantly more likely than young men to predict that their children will do better financially than they have done (66% vs. 55%).

At the same time, minorities are far more optimistic about their children’s future than are whites. More than seven-in-ten young blacks (71%) and a slightly larger share of young Hispanics (77%) expect that their children will have a better standard of living. In contrast, barely half of all young whites (52%) are equally optimistic about their children’s financial futures.

At the same time, minorities are far more optimistic about their children’s future than are whites. More than seven-in-ten young blacks (71%) and a slightly larger share of young Hispanics (77%) expect that their children will have a better standard of living. In contrast, barely half of all young whites (52%) are equally optimistic about their children’s financial futures.

Young college graduates and more affluent young adults also are significantly less hopeful that their children will do better financially than they have done. According to the survey, only four-in-ten college graduates ages 18 to 34 (42%) are optimistic that their children will do better economically than they have. More than one-third (35%) expect their children will do about the same as they have.

In contrast, about two-thirds of all those ages 18 to 34 who do not have a college degree (67% of those enrolled in school and 65% of those not enrolled) are confident that their children will surpass them.

Achieving their Goals

In spite of the optimism gap between young and old in looking at their financial future, when it comes to meeting the broader goals in life, the generations have a similar outlook. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of adults ages 18 to 34 are optimistic that they will eventually achieve their goals in life or say they already have achieved them. A similar share of adults ages 35 and older (70%) also say they expect to accomplish their goals or already have attained them.

Not surprisingly, older adults are more likely than their younger counterparts to say they have already reached their goals (33% among those ages 35 and older versus 9% of those under age 35). A majority of young adults (64%) say they are optimistic that they will be able to achieve their goals.

Not surprisingly, older adults are more likely than their younger counterparts to say they have already reached their goals (33% among those ages 35 and older versus 9% of those under age 35). A majority of young adults (64%) say they are optimistic that they will be able to achieve their goals.

What is surprising is that the share of each age group saying they are worried that they will face many difficulties that might prevent them from achieving their goals is nearly identical. In spite of their different stages in life, 25% of those ages 18 to 34 and 26% of those ages 35 and older say they are more worried than optimistic about their future.

The belief among the young that they will achieve their life goals varies only slightly, if at all, among key demographic groups. Young men are just as likely as young women to say they expect to fulfill their ambitions (65% vs. 63%). Roughly six-in-ten young whites (62%) and a slightly larger share of young Hispanics (65%) are optimistic they will reach their goals, a view shared by 70% of young blacks.

But the survey found that young adults ages 18 to 34 who did not graduate from college and are not currently in school are the most concerned about falling short of their objectives. About three-in-ten of these less educated young adults (31%) say they are more worried than optimistic about accomplishing their goals in life, compared with 2o% of those who are either college graduates or are still in school.

What Goals Are Most Important?

What types of goals are young people so optimistic about? In putting value to the different aspects of their lives, both young and older adults place more emphasis on parenting and marriage than on more material items, such as a high-paying career or home ownership.

What types of goals are young people so optimistic about? In putting value to the different aspects of their lives, both young and older adults place more emphasis on parenting and marriage than on more material items, such as a high-paying career or home ownership.

More than half (54%) of young adults ages 18 to 34 say being a good parent is “one of the most important things” in their life, and an additional 39% say it is “very important but not the most.”

Over a third of young adults (34%) say having a successful marriage is one of the most important things, and 51% say it is very important.

Similar shares of adults ages 35 and older say these two items are of top importance—53% of the older group says parenting is one of the most important things in their life (an additional 40% say this is very important). And 37% say having a successful marriage is one of the most important things in their life (46% say very important).

Compared with marriage and parenting, young adults place relatively less importance on career. Nevertheless, they are significantly more likely than older adults to say this is among the most important aspects of their life. Nearly a quarter (22%) of 18- to 34-year-olds say having a job that benefits society is one of the most important things in their life. Only 14% of those ages 35 and older say the same. And while 15% of young adults say being successful in a high-paying career is of utmost importance, less than half the share of older adults agrees (7%).

There is no significant difference between young and older adults in terms of the importance of owning their own home. Roughly one-in-five young adults (18%) and nearly the same share of adults ages 35 and older (22%) say owning a home is one of the most important things in their life.

In addition, there is no difference between young and older adults in the importance of becoming famous—only 1% of each group says becoming famous is one of the most important things in their life.

The youngest among the 18 to 34 age group are even more career-focused than their older half. More than three-quarters (76%) of 18- to 24-year-olds rate a high-paying career or profession as one of the most important things or very important, while 25- to 34-year-olds are more moderate with 51% rating this so highly. Furthermore, 79% of 18- to 24-year-olds say having a job or career that benefits society is one of the most important things or very important; 66% of 25- to 34-year-olds agree.

The youngest among the 18 to 34 age group are even more career-focused than their older half. More than three-quarters (76%) of 18- to 24-year-olds rate a high-paying career or profession as one of the most important things or very important, while 25- to 34-year-olds are more moderate with 51% rating this so highly. Furthermore, 79% of 18- to 24-year-olds say having a job or career that benefits society is one of the most important things or very important; 66% of 25- to 34-year-olds agree.

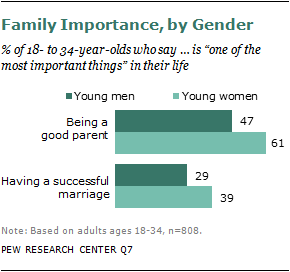

Among young adults, several significant demographic differences emerge. For example, there is a gender split in the importance of marriage and parenting. While 61% of young women ages 18 to 34 list being a good parent as one of the most important things in their life, less than half of men (47%) say the same. And while 39% of women rate a successful marriage among their top priorities, only 29% of men place the same value on that.

Several differences also appear among racial and ethnic categories of young adults. Fully 37% of young white adults, compared with only 22% of young black adults, say a successful marriage is one of the most important things in their life. Hispanics lie in the middle and do not differ significantly from either group.

Several differences also appear among racial and ethnic categories of young adults. Fully 37% of young white adults, compared with only 22% of young black adults, say a successful marriage is one of the most important things in their life. Hispanics lie in the middle and do not differ significantly from either group.

Compared with whites, greater shares of both black and Hispanic young adults say owning their own home is among their top priorities. While 25% of blacks and 26% of Hispanics say

Compared with whites, greater shares of both black and Hispanic young adults say owning their own home is among their top priorities. While 25% of blacks and 26% of Hispanics say

owning a home is of the highest importance in their lives, only 12% of whites say the same.

Additionally, young blacks and Hispanics are more likely to value becoming famous than young white adults. Only 2% of whites ages 18 to 34 say becoming famous is one of the most important things or very important, but 15% of blacks and 13% of Hispanics rate fame as highly important.