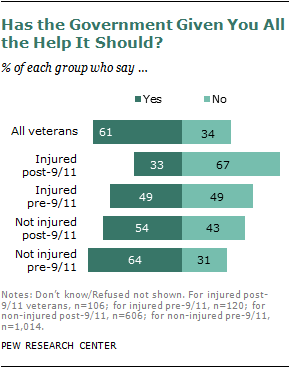

Among wounded warriors, those who served since 9/11 are more likely than veterans from earlier eras to say their transition to the civilian world has been difficult; to report they have suffered from PTS as a consequence of their military service; and to say that the government has not done enough to help them.4

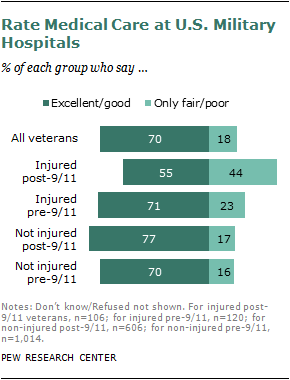

Veterans badly hurt in the post-9/11 era also are more likely than other veterans, regardless of era or whether they were injured, to say the government has not given them all the help it should. These recent veterans also are far more critical than older veterans of the Veterans Administration5 and the quality of medical care that injured soldiers have received from military hospitals in the United States.

Veterans badly hurt in the post-9/11 era also are more likely than other veterans, regardless of era or whether they were injured, to say the government has not given them all the help it should. These recent veterans also are far more critical than older veterans of the Veterans Administration5 and the quality of medical care that injured soldiers have received from military hospitals in the United States.

Less Satisfaction with Family Life

According to the survey, only about half (49%) of all injured recent veterans say they are “very satisfied” with the quality of their family lives. In contrast, about two-thirds of older injured veterans (66%) expressed satisfaction with things at home, as do similar shares of uninjured veterans, regardless of era.

This dissatisfaction is echoed by another finding among veterans who were married or had young children while serving. Among this group, a majority of injured post-9/11 veterans but only a third of older injured veterans say the military did an “only fair” or “poor” job of meeting the needs of their families while they were deployed (54% vs. 34%). Only about three-in-ten (30%) of uninjured post-9/11 veterans and 21% of uninjured veterans from previous eras are similarly critical of the military’s treatment of their families while on deployment.

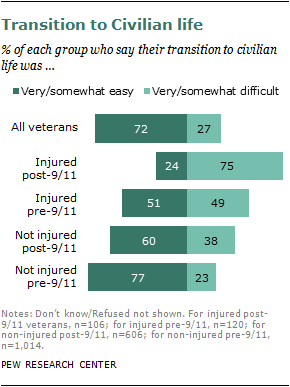

The difficulties that many post-9/11 veterans have faced transitioning from the military to civilian life likely explain some of their current dissatisfaction with their family life. According

The difficulties that many post-9/11 veterans have faced transitioning from the military to civilian life likely explain some of their current dissatisfaction with their family life. According

to the survey, three-in-four (75%) injured post-9/11 veterans say their transition to life after the military was difficult, compared with 49% of older injured veterans and smaller proportions of those who were not badly hurt in the post-9/11 or pre-9/11 eras (38% and 23%, respectively).

Post-9/11 veterans who were badly hurt while serving are far more likely than other injured veterans to report they suffered from posttraumatic stress (66% vs. 43%). They also are significantly more likely to say they experienced an emotionally traumatic event while serving (81% vs. 51% for veterans seriously injured in earlier eras)—a difference that persists even when the analysis focuses only on veterans of both eras who were badly hurt in combat.

While the sample size is small, the wounded warriors of the post-9/11 era also are more likely than other veterans, regardless of era or experience with injuries, to say the government has failed to provide them with all the help it should (67% vs. 49% for injured pre-9/11 veterans and 43% of uninjured post-9/11 veterans). The newest generation of wounded warriors also is far more critical of the Veterans Administration and the medical care that veterans receive in stateside military hospitals.

Nearly two-thirds of all injured post-9/11 veterans say the Veterans Administration is doing an only fair or poor job of meeting the needs of those who have served. In contrast, only 37% of

veterans seriously hurt while serving in earlier eras rate the Veterans Administration as low.

Veterans who were seriously injured in the post-9/11 period also are more than twice as likely as other injured service members to be critical of the care that injured veterans are receiving in U.S. military hospitals (44% judge the care to be only fair or poor, compared with a similar rating by 17% of those who were not injured).

Veterans who were seriously injured in the post-9/11 period also are more than twice as likely as other injured service members to be critical of the care that injured veterans are receiving in U.S. military hospitals (44% judge the care to be only fair or poor, compared with a similar rating by 17% of those who were not injured).

It should be noted that service members who experienced the worst of earlier wars and survived may already have died in the years or decades since they were discharged. For surviving injured veterans of these previous conflicts, the memory of the burdens they bore also may have faded, while the struggles of recent wounded veterans remain vivid and fresh.

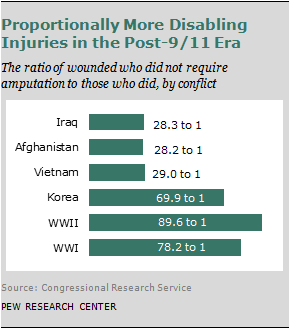

At the same time, war in the post-9/11 period has changed. Combat has become less lethal than in the earlier wars. Proportionately more soldiers now survive shattering injuries that would have killed their predecessors. However, they are often left to deal with the emotional and physical consequences of their injuries for the rest of their lives—and these experiences can color their attitudes toward the military.

At the same time, war in the post-9/11 period has changed. Combat has become less lethal than in the earlier wars. Proportionately more soldiers now survive shattering injuries that would have killed their predecessors. However, they are often left to deal with the emotional and physical consequences of their injuries for the rest of their lives—and these experiences can color their attitudes toward the military.

According to Department of Defense casualty data compiled for each major U.S. war, troops fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan survive 88% of all combat injuries, compared with 72% in Vietnam, 63% in World War II and 44% in the Civil War.

However, these medical miracles go only so far. Wounds that are not fatal can often be disabling. The ratio of wounded but not amputated-to-amputations in post-9/11 combat is virtually unchanged from Vietnam. Significantly fewer wounded soldiers underwent amputations in World War II because more died of their battlefield injuries, according to researchers Anne Leland and Mari-Jana Oboroceanu of the Congressional Research Service in a 2010 report to Congress.6

However, these medical miracles go only so far. Wounds that are not fatal can often be disabling. The ratio of wounded but not amputated-to-amputations in post-9/11 combat is virtually unchanged from Vietnam. Significantly fewer wounded soldiers underwent amputations in World War II because more died of their battlefield injuries, according to researchers Anne Leland and Mari-Jana Oboroceanu of the Congressional Research Service in a 2010 report to Congress.6

Citing data from the Office of the Surgeon General, Leland and Oboroceanu reported that the ratio of wounded-toamputations stood at 28.3 to 1 in Iraq and Afghanistan. That means that for every 29 service members wounded in combat, one required amputation. In Vietnam, that ratio was slightly higher (29.0 to 1), while in World War II, it stood at 69.9 to 1.

An inevitable consequence of these successful efforts to save the lives of wounded service members has been to swell the ranks of disabled veterans. Today, about three-in-ten post-9/11 veterans have been determined by the Department of Defense or the Department of Veterans Affairs to have some level of disability from service-related injuries, illnesses or psychological conditions such as PTS. Among these disabled veterans, nearly six-in-ten are at least 30% disabled and four-in-ten have lost at least half of their normal ability to function.

Views on the Military, the Post-9/11 Wars and Their Service

Veterans seriously injured while serving in the post-9/11 era are more critical of the military than are recent veterans who were not seriously injured while serving.

Veterans seriously injured while serving in the post-9/11 era are more critical of the military than are recent veterans who were not seriously injured while serving.

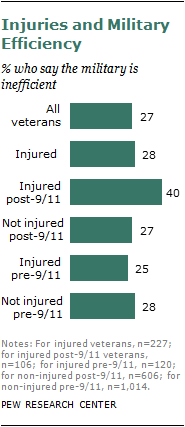

According to the survey, four-in-ten (40%) injured veterans who served after 9/11 say the military operates “inefficiently,” compared with only 27% who were not injured. Among veterans who served in earlier periods, there is no difference in the views of those who were injured and uninjured: About a quarter say the military operates inefficiently (25% injured, 28% not injured).

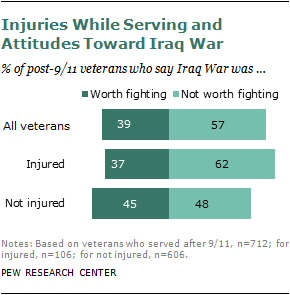

At the same time, more than six-in-ten injured post-9/11 veterans (62%) are critical of the war in Iraq, compared with 48% of recent veterans who were not injured.

In their judgment of the Iraq War, these injured veterans appear to be more like veterans from earlier eras: 57% of injured and 58% of uninjured pre-9/11 veterans say Iraq has not been worth it.

Attitudes toward the war in Afghanistan reflect a similar pattern. Among all recent veterans, those who were seriously injured are more likely than other veterans to say this war was not worth the cost (52% vs. 40%), a finding that falls just short of being statistically significant because of the relatively small size of the samples.

Attitudes toward the war in Afghanistan reflect a similar pattern. Among all recent veterans, those who were seriously injured are more likely than other veterans to say this war was not worth the cost (52% vs. 40%), a finding that falls just short of being statistically significant because of the relatively small size of the samples.

Injuries and the Rewards and Burdens of Service

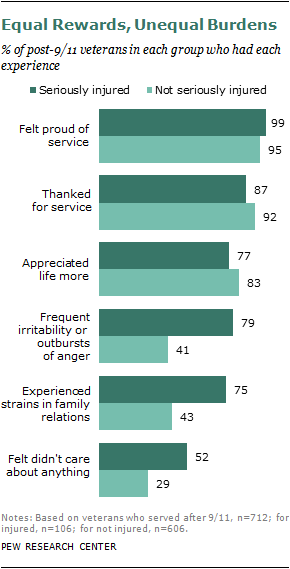

Injured and uninjured veterans have shared equally in the rewards that military service brings to those who fought in the post-9/11 era. At the same time, recent veterans who were seriously hurt and their families bear more burdens of service than their uninjured comrades once they leave the military, according to a series of questions asked only of those who served since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Injured and uninjured veterans have shared equally in the rewards that military service brings to those who fought in the post-9/11 era. At the same time, recent veterans who were seriously hurt and their families bear more burdens of service than their uninjured comrades once they leave the military, according to a series of questions asked only of those who served since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Regardless of whether they had been injured, more than nine-in-ten post-9/11 veterans are proud of their service. Nearly as many report that they have been thanked for their service since their discharge. More than three-quarters of both groups say they have appreciated life more since they left active duty (77% for injured veterans vs. 83% for uninjured).

But injured veterans and their families must deal with problems that other veterans are far less likely to face. For example, three-quarters of injured post 9/11 veterans say they have

experienced strains in family relations since leaving the military. In contrast, slightly more than four-in-ten (43%) uninjured post-9/11 veterans say they have had difficulties at home since they were discharged.

About eight-in-ten (79%) injured post-9/11 veterans say they have experienced frequent incidents of irritability or outbursts of anger since leaving the military, nearly double the proportion of non-injured recent veterans who have experienced these things (41%).

About half (52%) say they have felt that they “didn’t care about anything” since leaving the service, compared with 29% of other recent veterans.

Other Differences

Post-9/11 veterans who were injured also differ in other ways from other recent veterans. Perhaps predictably, they are in significantly worse health: about six-in-ten say their current health is only fair or poor, nearly triple the proportion of uninjured recent veterans (59% vs. 21%) who give the same response. Results among veterans from previous eras reflect the same pattern, though the difference between the two groups is smaller: 47% of those who were injured reported that they were in only fair or poor health, compared with 29% of those who were not injured.

And while the sample size is small, only 18% of post-9/11 veterans who were seriously injured say they are “very happy” with their lives overall, compared with 31% of their uninjured comrades.