When it comes to their armed forces, most Americans in the post-9/11 era have feelings of pride, gratitude and confidence. At the same time, most Americans acknowledge they know little about the realities of military service. And, in increasing numbers, they disapprove of or do not pay attention to the wars the military is currently fighting.

Fully nine-in-ten Americans say they have felt proud of the troops in Afghanistan and Iraq since those two wars began. But a large majority (71%) of this same public says most Americans have little or no understanding of the problems faced by those in the military.

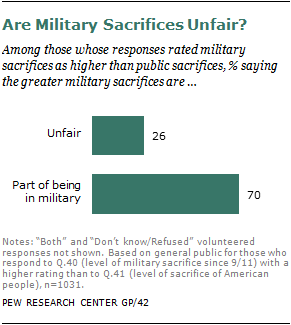

The public is aware that since the 9/11 attacks, members of the military and their families have carried greater burdens than the American people. More than eight-in-ten (83%) say that members of the military and their families have had to make a lot of sacrifices, while only 43% say so about the American public. But among those whose responses rate the military’s sacrifice as greater than the public’s (47% of respondents), seven-in-ten see nothing unfair in this disparity. Rather, they agree that “it’s just part of being in the military.”

The public is aware that since the 9/11 attacks, members of the military and their families have carried greater burdens than the American people. More than eight-in-ten (83%) say that members of the military and their families have had to make a lot of sacrifices, while only 43% say so about the American public. But among those whose responses rate the military’s sacrifice as greater than the public’s (47% of respondents), seven-in-ten see nothing unfair in this disparity. Rather, they agree that “it’s just part of being in the military.”

In another indication of the distance many Americans feel from the troops, half of the public says the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have had little impact on their own lives. Also, most Americans accept the status quo of an all-volunteer fighting force and disapprove of reinstating a compulsory draft that would expand the pool of potential soldiers more broadly throughout society.

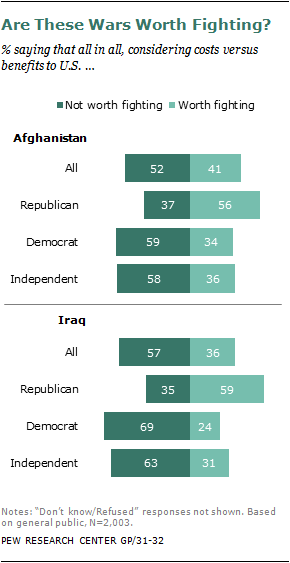

Even as they express pride in the troops, most Americans have soured on the post-9/11 wars. A majority (57%) says the war in Iraq has not been worth fighting, and nearly as many (52%) say the same about the war in Afghanistan. This marks a change of heart from when each of these wars began. Other survey data show the public is paying far less attention to both conflicts now than at earlier stages of the fighting.

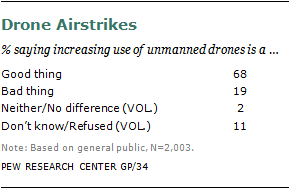

Americans are evenly divided (45% favor, 48% oppose) about whether the military should be engaged in “nation-building” activities, which focus on improving the physical, political and social infrastructure of Afghanistan and Iraq. However, the public is strongly supportive of the military’s other major military tactical innovation of the post-9/11 wars—the use of unmanned “drone” aircraft for aerial strikes against individual enemy targets. About two-thirds (68%) of the public say increased use of drones is a good thing (and an even larger share of veterans supports their use).

Americans hold a very favorable opinion of the military as an organization. At a time when the public’s confidence in most key national institutions has sagged, confidence in the military is at or near its highest level in many decades. Most people also say they believe the military operates efficiently.

But confidence is one thing; the inclination to encourage young people to join is another. Only about half of Americans (48%) say they would advise a young person to join the military, well below the share of post-9/11 veterans (82%) or pre-9/11 veterans (74%) who say they would give the same advice.

This chapter analyzes public attitudes on a variety of fronts about the nation’s troops, the military as an institution and the current wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. It is based mainly on a survey of 2,003 Americans taken Sept. 1-15, 2011. On some findings, it compares the public’s attitudes with those of veterans, using surveys conducted July 18-Sept. 4, 2011, among 1,853 Americans who have served in the military.

Public Views of the Military

Whatever their views about the wars themselves, Americans have a high opinion of the troops serving in Afghanistan and Iraq. Nine-in-ten Americans (91%) say they have felt proud of the soldiers serving in the military since those two wars began. In this, they match the attitudes of post-9/11 veterans themselves, 96% of whom say they felt proud to serve.

Whatever their views about the wars themselves, Americans have a high opinion of the troops serving in Afghanistan and Iraq. Nine-in-ten Americans (91%) say they have felt proud of the soldiers serving in the military since those two wars began. In this, they match the attitudes of post-9/11 veterans themselves, 96% of whom say they felt proud to serve.

A majority of Americans say they have expressed their admiration directly. Three-quarters (76%) say that since those wars began, they have thanked someone in the military for serving. Looking at this question from the troops’ perspective, nearly all veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (92%) say someone has thanked them for their service since they were discharged.

More than half of Americans (58%) say they have done something to help someone in the military or to help a military family. They are particularly likely to say so (71%) if they also say they have a family member or close friend who served in Afghanistan or Iraq.

These findings fit a broader pattern of high public confidence in the U.S. military. As other institutions have lost favor in American public opinion, the standing of the military has grown. In a 2011 Gallup survey, the share of Americans who say they have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the military was 78%. The military got the highest rating among 16 institutions tested, among them the church or organized religion (48%), big business (19%) and Congress (12%).

These findings fit a broader pattern of high public confidence in the U.S. military. As other institutions have lost favor in American public opinion, the standing of the military has grown. In a 2011 Gallup survey, the share of Americans who say they have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the military was 78%. The military got the highest rating among 16 institutions tested, among them the church or organized religion (48%), big business (19%) and Congress (12%).

Of the institutions tested in the Gallup series, which began in the 1970s, the military is the only one that has had a notable gain in public confidence. Public confidence in the military surpassed confidence in religious organizations in the late 1980s and has stayed there ever since. Among other institutions losing stature since then are banks, public schools and organized labor. A few institutions, including the police, small business and health maintenance organizations, for which confidence questions have been asked since the 1990s, have neither gained nor lost. The criminal justice system has gained some public confidence since the early 1990s.

In another demonstration of public approval of the military, when Americans were asked in a 2009 Pew Research Center survey about the contributions of various groups to society, 84% said members of the military contribute a lot. By comparison, 77% said so about teachers, 70% about scientists and 69% about medical doctors.19

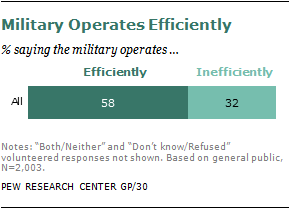

Overall, Americans perceive the all-volunteer military as operating efficiently. A 58% majority says the military operates efficiently, while a third (32%) says it operates inefficiently.

Overall, Americans perceive the all-volunteer military as operating efficiently. A 58% majority says the military operates efficiently, while a third (32%) says it operates inefficiently.

Blacks (74%) and Hispanics (69%) are more likely than whites (55%) to see the military as operating efficiently; women (61%) are more likely than men (56%) to say the same. Democrats are more likely than either Republicans or independents to say the same.

Despite positive views of the military as an organization, some Americans have mixed feelings about the military’s conduct in Afghanistan and Iraq. About a third (34%) say they have felt ashamed of something the military had done in Afghanistan or Iraq. The question did not mention any specific incidents.

Young adults ages 18-29 (42%) are more likely than Americans ages 50-64 (33%) or ages 65 and older (27%) to say so. By education level, college graduates (45%) are the most likely to say they have felt ashamed of something the military has done. By party affiliation, Democrats (40%) and independents (37%) are more likely to say so than Republicans (24%).

Military and Public Sacrifice

Overwhelmingly, the public sees that members of the armed forces and military families have made a lot of sacrifices since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Less than half believes that the American people have had to make a lot of sacrifices. But most of those who say veterans and their families have sacrificed more than the public say the disparity is part of military life.

Overwhelmingly, the public sees that members of the armed forces and military families have made a lot of sacrifices since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Less than half believes that the American people have had to make a lot of sacrifices. But most of those who say veterans and their families have sacrificed more than the public say the disparity is part of military life.

Eight-in-ten Americans (83%) say veterans and military families have made a lot of sacrifices since 9/11, and 14% say they have made some sacrifices.

By contrast, only four-in-ten (43%) say the American people have made a lot of sacrifices and 39% say they have made some sacrifices. Blacks (51%) and Hispanics (61%) are notably more likely than whites (38%) to say the American people have made a lot of sacrifices.

Nearly one-in-five people (18%) say the American public has made hardly any or no sacrifices. Whites (22%) are more likely to voice this view than blacks (6%) or Hispanics (9%). Adults 65 and older (22%) are more likely to say so than young adults 18-29 (14%).

However, among those whose responses rated the military’s sacrifice as higher than the American public’s sacrifice—47% of those surveyed—most do not think it unfair. Seven-in-ten say that is “just part of being in the military,” while 26% say it is unfair that the military has sacrificed more. Men (75%) are more likely than women (65%) to say it is part of being in the military. Women (31%) are more likely than men (21%) to say it is unfair.

War Fatigue

The view that Americans have not had to sacrifice a lot since the 9/11 attacks is matched by Americans’ assessment of the impact of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars on their own lives. Half of Americans (50%) say the two wars have made little difference in their lives.

This finding meshes with other Pew Research Center survey data indicating that the American public has turned its gaze away from the two wars. Only 36% say Iraq or Afghanistan comes up in conversation with family or friends, compared with 68% who say the economy comes up in conversation. And in the past two years, only about a quarter of Americans have said they pay close attention to either war. By comparison, half followed news about Iraq very closely in 2002-2003, and 40% or more paid very close attention to news about Afghanistan in 2001-2002.20

Public Understanding of the Military

Although they admire the military, most Americans acknowledge that the public has a poor understanding of the rewards or the challenges of serving in the armed forces. Veterans share that opinion.

Although they admire the military, most Americans acknowledge that the public has a poor understanding of the rewards or the challenges of serving in the armed forces. Veterans share that opinion.

Less than half of Americans say the public understands the benefits and rewards of military service very well (12%) or even fairly well (32%). The share of veterans who say so is even lower—only 5% of veterans say the public understands the positive side of military service very well, and 24% say fairly well.

Asked how well the American people understand the problems that those in the military face, only 8% say they do so very well and 19% say they do so fairly well. The shares of veterans who say so are 3% for very well and 18% for fairly well.

Blacks (40%) and Hispanics (44%) are more likely than whites (22%) to say the American people understand the problems faced by those in the military. Blacks (49%) and Hispanics (59%) also are more likely than whites (41%) to say the public understands the rewards and benefits of military service.

Public’s Advice about a Military Career

Americans are ambivalent about whether they would advise a young person close to them to join the military: 48% say they would, and 41% say they would not. Veterans, by comparison, are more enthusiastic: Three-quarters say they would, including 74% of those who served before the 9/11 attacks and 82% of those who have served since 9/11.

Americans are ambivalent about whether they would advise a young person close to them to join the military: 48% say they would, and 41% say they would not. Veterans, by comparison, are more enthusiastic: Three-quarters say they would, including 74% of those who served before the 9/11 attacks and 82% of those who have served since 9/11.

There are notable differences by gender, region and political party. Men (53%) are more likely than women (43%) to recommend a military career, and Republicans (64%) are more likely than Democrats (42%). The South is the only region where more than half (53%) say they would recommend a military career to a young person they know.

There also are notable gender differences among those who live in the South: 60% of Southern men but only 47% of Southern women say they would recommend a military career to a young person they know. A similar split exists among Republicans: 72% of Republican men but only 56% of Republican women would recommend a military career.

By age group, young adults ages 18-29 (51%) are more likely than other age groups to recommend against joining the military. Those who say they have a family member or close friend who served in Afghanistan or Iraq also are more likely (54%) to advise a military career.

Contact with Veterans

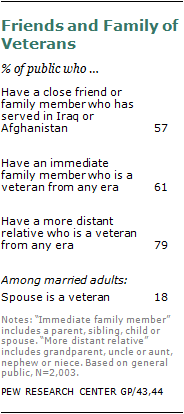

Nearly six-in-ten Americans (57%) report that they have a close friend or family member who served in the wars in either Iraq or Afghanistan.

Nearly six-in-ten Americans (57%) report that they have a close friend or family member who served in the wars in either Iraq or Afghanistan.

In addition, about six-in-ten (61%) survey respondents say they have at least one immediate family member (a parent, sibling, child or spouse) who has served in the military at some point in the past. Older adults are more likely to have an immediate family member who served in the military. About eight-in-ten adults (79%) ages 50 to 64 have an immediate family member who has served; by comparison, about a third of adults ages 18 to 29 (33%) have an immediate family member who has served in the military. Republicans (73%) are more likely than either Democrats (59%) or independents (56%) to have a veteran in their immediate family.

About eight-in-ten adults (79%) have a more distant relative (a grandparent, uncle, aunt, nephew, or niece) who has served in the military.

Public Views of Military Policy and Performance

A majority of the public sees the military as operating efficiently and approves of the job President Obama is doing as commander in chief. At the same time, however, most Americans do not see either the war in Afghanistan or in Iraq as worth fighting.

Commander in Chief

A majority of Americans give Obama positive marks for his performance as commander in chief; 53% approve of his performance in this regard while about four-in-ten (39%) disapprove. Opinion of the president’s performance as commander in chief is more positive than ratings of his overall job performance. In an August 2011 Pew Research survey, 43% of Americans approved of the president’s job performance and 49% disapproved.21

A majority of Americans give Obama positive marks for his performance as commander in chief; 53% approve of his performance in this regard while about four-in-ten (39%) disapprove. Opinion of the president’s performance as commander in chief is more positive than ratings of his overall job performance. In an August 2011 Pew Research survey, 43% of Americans approved of the president’s job performance and 49% disapproved.21

The groups most supportive of Obama’s performance as commander in chief include African-Americans, Hispanics, and Democrats. Fully eight-in-ten (80%) Democrats approve of Obama’s performance as the head of the military. Republicans take the opposite view, with seven-in-ten (70%) disapproving of Obama’s performance. Independents are narrowly divided; 48% approve and 43% disapprove.

Younger adults tend to be more positive than older adults about Obama’s performance in this regard. Adults under age 50, by 57% to 35%, approve of Obama’s performance as head of the military. Those ages 50 and older are more narrowly divided; 48% approve and 43% disapprove. Men and women are equally likely to approve of the president’s performance.

Post-9/11 Wars: Afghanistan and Iraq

Ten years into the conflict in Afghanistan, the American public questions the war’s value. All told, 41% of Americans say the war in Afghanistan has been worth fighting, while a 52% majority says it has not. Opinion varies along partisan lines. A majority of Republicans (56%) say the Afghanistan War has been worth fighting. Among Democrats and independents, a majority takes the opposite stance (59% and 58%, respectively).

Ten years into the conflict in Afghanistan, the American public questions the war’s value. All told, 41% of Americans say the war in Afghanistan has been worth fighting, while a 52% majority says it has not. Opinion varies along partisan lines. A majority of Republicans (56%) say the Afghanistan War has been worth fighting. Among Democrats and independents, a majority takes the opposite stance (59% and 58%, respectively).

This “has-it-been-worth-it?” question yields a more downbeat assessment from the public than has been the case with differently worded questions about Afghanistan that the Pew Research Center has asked over the years. For example, surveys taken from 2006 to 2011 found a majority of respondents believed the U.S. made the right decision to use force in Afghanistan. And 58% of Americans believed the U.S. would either definitely or probably meet its goals in Afghanistan, according to a June 2011 Pew Research survey.22

Opinion about the war in Iraq has the same tenor. About six-in-ten (57%) Americans say in this new Pew Research survey that the war in Iraq has not been worth fighting, while 36% say it has been.

The majority view that the Iraq War has not been worth fighting holds across gender, race and ethnicity, age, education, and region. The exception is political party. Democrats and Republicans are on opposite sides of this issue. About six-in-ten (59%) Republicans say the war in Iraq has been worth fighting. In contrast, about seven-in-ten (69%) Democrats and 63% of independents say the war has not been worth fighting.

Assessments of the Iraq War today are in keeping with the public’s past judgments about U.S. military involvement in Iraq. Within five years of the start of conflict in Iraq, a majority of the public called the use of force in Iraq the “wrong decision” and the public was evenly divided over how well the war was going.23

Today, Americans appear skeptical that either war has improved national security in this country. In a recent Pew Research survey, 31% said U.S. involvement in Iraq has increased the chances of another terrorist attack at home, 26% said it has lessened the chances and 39% said it has made no difference. Evaluations of the war in Afghanistan were similar—37% said it has increased chances of another terrorist attack in the U.S., 25% said it has lessened the chances and 34% said it has not made a difference.24

Asked which of two statements comes closer to their own views, a Pew Research survey found that 52% of Americans say that relying too much on military force to defeat terrorism creates hatred that leads to more terrorism, while 38% say that using overwhelming military force is the best way to defeat terrorism.25 Post-9/11 veterans hold similar views, with 51% saying that relying too much on military force creates hatred that leads to more terrorism and 40% saying that overwhelming military force is the best way to defeat terrorism.

Military Tactics

The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been notable for the heavy emphasis the military has placed on noncombat “nation-building” objectives, such as infrastructure reconstruction and efforts to strengthen political and economic institutions.

The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been notable for the heavy emphasis the military has placed on noncombat “nation-building” objectives, such as infrastructure reconstruction and efforts to strengthen political and economic institutions.

The public is closely divided over whether such roles are appropriate (45%) or inappropriate (48%) for the military.

Younger adults tend to be more supportive than older adults of such activities. A majority (52%) of younger adults, ages 18 to 29, consider nation-building activities appropriate. A narrow majority of those ages 50 and older take the opposite stance. Among those ages 65 and older, 33% say nation-building roles are appropriate for the military and 49% say they are not.

Republicans tend to say that nation-building activities are not appropriate for the military, while Democrats tend to say they are appropriate. However, neither partisan group shows strong consensus on this issue.

Views about nation building are closely aligned with opinion about whether or not the post-9/11 wars have been worth fighting. Not surprisingly, those who consider nation-building activities inappropriate are especially likely to believe the wars in Afghanistan and in Iraq have not been worth fighting.

Another military tactic associated with these wars—the use of drones for aerial strikes aimed at al Qaeda or other enemy targets—draws much more favorable reviews from the public. More than two-thirds (68%) of Americans consider the use of drones in the U.S. military a good thing; just 19% say it is a bad thing.

Another military tactic associated with these wars—the use of drones for aerial strikes aimed at al Qaeda or other enemy targets—draws much more favorable reviews from the public. More than two-thirds (68%) of Americans consider the use of drones in the U.S. military a good thing; just 19% say it is a bad thing.

This balance of opinion holds across gender, race and ethnicity, age, education, region and even political party. A majority of Republicans, Democrats and independents all consider the use of unmanned aircraft for airstrikes to be a good thing. Post-9/11 veterans consider the increased use of drones by the military a good thing by an even wider margin (87% to 7%).

Keep It Volunteer

More than 35 years after the end of military conscription in 1973, three-quarters (74%) of the public opposes reinstating a draft, while one-fifth (20%) favor a return to the draft.

More than 35 years after the end of military conscription in 1973, three-quarters (74%) of the public opposes reinstating a draft, while one-fifth (20%) favor a return to the draft.

The majority-disapproval of returning to a draft holds across gender, race and ethnicity, age, education, region, and political party. However, there are notable differences among some groups.

Men, for example, are somewhat more likely than women to favor a return to a military draft (23% to 16%). By age group, Americans ages 65 and older (29%) are more likely than younger groups to favor a military draft; only 14% of young adults ages 18-29 do so. Whites (78%) and blacks (71%) are more likely than Hispanics (58%) to oppose reinstating military conscription.