The risks and rewards of military service carry over into civilian life. When servicemen and women retire or are discharged from the military, they leave with skills, knowledge and experiences that can help them advance in the future. Yet many also carry with them deep and enduring scars.

Large majorities of veterans—pre- and post-9/11—say the military helped them get ahead in life. They stress the character-building aspects of their experience: learning to work with other people, building self-confidence and growing as a person. Most veterans say their readjustment to civilian life was easy. However, a significant share (44% among post-9/11 veterans) say it was difficult.

The burdens of re-entry have been particularly acute for America’s combat veterans. Among post-9/11 veterans who served in combat, 76% say their military experience helped them get ahead, yet half (51%) say they had some difficulty readjusting to civilian life. Majorities of these combat veterans report strained family relations and frequent incidents of irritability or anger. Fully half (49%) say they have likely suffered from post-traumatic stress. And many question whether the government has done all it should to support them. Still, they express a deep sense of pride in their service and an increased appreciation for life.

The burdens of re-entry have been particularly acute for America’s combat veterans. Among post-9/11 veterans who served in combat, 76% say their military experience helped them get ahead, yet half (51%) say they had some difficulty readjusting to civilian life. Majorities of these combat veterans report strained family relations and frequent incidents of irritability or anger. Fully half (49%) say they have likely suffered from post-traumatic stress. And many question whether the government has done all it should to support them. Still, they express a deep sense of pride in their service and an increased appreciation for life.

The Advantages of Military Service

Overall, veterans report that their military experience has helped them get ahead in life. Two-thirds say it has helped them a lot, and 14% say it has helped a little. An additional 16% say their military experience hasn’t made a difference in terms of getting ahead in life. Only 3% say the experience was detrimental.

Within the veteran community, this sense of being helped by virtue of serving in the military is nearly universal. Among men and women, young and old, blacks, whites and Hispanics, strong majorities say their military experience has helped them get ahead in life. Additionally,

Within the veteran community, this sense of being helped by virtue of serving in the military is nearly universal. Among men and women, young and old, blacks, whites and Hispanics, strong majorities say their military experience has helped them get ahead in life. Additionally,

veterans across military eras agree that their service was beneficial. Whether they served in a prior war, during the relative peacetime after Vietnam and before 9/11, or during the past decade, veterans are likely to say having served in the military gave them an advantage in life.

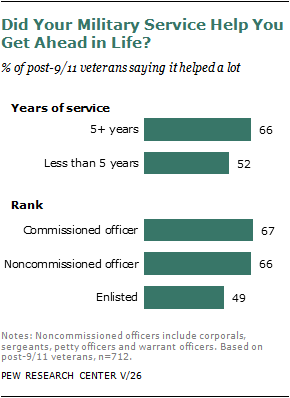

Among post-9/11 veterans, those who served five or more years in the military are more likely to see a benefit from their service. Two-thirds of those who served at least five years say the experience helped them a lot in terms of getting ahead in life. This compares with only half (52%) of those who served for less than five years.

Officers—both commissioned and noncommissioned—are much more likely than enlisted personnel to say that their military service helped them get ahead. Roughly two-thirds of officers say their military experience helped them a lot, versus only 49% of veterans who were among the rank-and-file enlisted personnel.

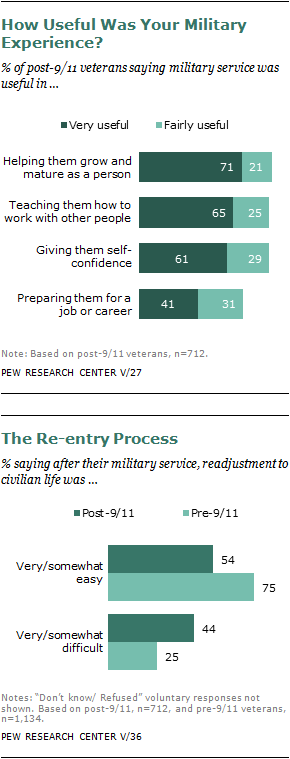

Not only do veterans feel the military helped them get ahead in life, but they also see specific benefits from their service. Among all post-9/11 veterans, 71% say their military experience was very useful in helping them grow and mature as a person; an additional 21% say it was fairly useful. Nearly as many (65%) say their time in the military was very useful in teaching them how to work together with other people (25% say fairly useful). And 61% say it was very useful in giving them self-confidence (29% fairly useful).

Veterans are less likely to report that their time in the military helped them get a job in the civilian world. Only 41% of post-9/11 veterans say their military experience was very useful in preparing them for a job or career. An additional 31% say it was fairly useful, and 27% say their military experience was not useful in this regard.

Veterans are less likely to report that their time in the military helped them get a job in the civilian world. Only 41% of post-9/11 veterans say their military experience was very useful in preparing them for a job or career. An additional 31% say it was fairly useful, and 27% say their military experience was not useful in this regard.

Re-entering Civilian Life

For many veterans of all eras, readjusting to civilian life after their military service has not been particularly difficult. More than seven-in-ten say their readjustment was very (43%) or somewhat (29%) easy. Still, more than one-in-four (27%) report that they had at least some difficulty readjusting.

The re-entry process has been more difficult for post-9/11 veterans than it was for those who served prior to 9/11. More than four-in-ten post-9/11 veterans (44%) say they had difficulty readjusting to civilian life, compared with 25% of pre-9/11 veterans. This may be due in part to the fact that post-9/11 veterans are much more likely than those who served before them to have seen combat. Among post-9/11 veterans who served in combat, half (51%) say they had difficulty readjusting to civilian life. This compares with 34% of post-9/11 veterans who did not see combat.

The combat experience clearly shapes an individual’s re-entry into civilian life. Post-9/11 veterans were asked whether they had experienced a range of things—some positive, some negative—since they were discharged from the service. In nearly every case, combat veterans had different experiences than veterans who did not serve in combat.

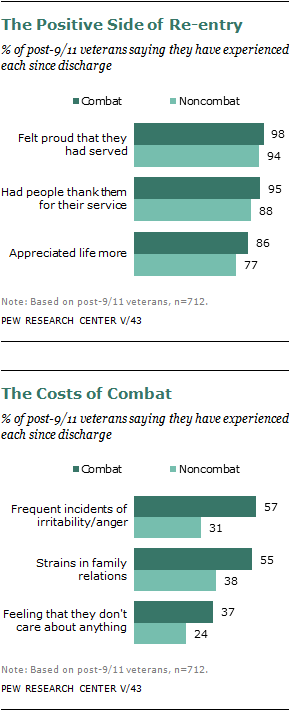

Virtually all post-9/11 combat veterans (98%) say that since they were discharged from the service, they have felt proud that they served in the military. Among veterans who did not serve in combat, the share is nearly as high (94%). Fully 95% of post-9/11 combat veterans say that since they got out of the military, people have thanked them for their service. This experience has been somewhat less prevalent among noncombat veterans (88%). A strong majority of all post-9/11 veterans say that since they left the military, they have felt a greater appreciation for life. This is true of 86% of combat veterans and 77% of those who were not in combat.

Virtually all post-9/11 combat veterans (98%) say that since they were discharged from the service, they have felt proud that they served in the military. Among veterans who did not serve in combat, the share is nearly as high (94%). Fully 95% of post-9/11 combat veterans say that since they got out of the military, people have thanked them for their service. This experience has been somewhat less prevalent among noncombat veterans (88%). A strong majority of all post-9/11 veterans say that since they left the military, they have felt a greater appreciation for life. This is true of 86% of combat veterans and 77% of those who were not in combat.

Veterans were also asked about some negative experiences that they may have had since leaving the military. Here the gaps between combat and noncombat veterans are much larger. Nearly six-in-ten post-9/11 combat veterans (57%) say that since being discharged from the military, they have experienced frequent incidents of irritability or outbursts of anger. By contrast, only 31% of noncombat veterans say the same. Nearly as many combat veterans (55%) say they have experienced strains in family relations. This compares with 38% of noncombat veterans.

Nearly four-in-ten combat veterans (37%) say that they have gone through periods when they felt as if they didn’t care about anything. Only 24% of noncombat veterans report feeling this way since leaving the military.

Veterans who retired as commissioned officers are much less likely than noncommissioned officers or rank-and-file enlisted personnel to say they have faced these types of emotional challenges. While 21% of commissioned officers say they have experienced frequent bouts of irritability or anger, fully half of noncommissioned officers (NCOs) and formerly enlisted veterans say they have had these experiences. Similarly, 13% of commissioned officers say they have felt that they didn’t care about anything, while the share among NCOs and enlisted personnel is more than twice as high.

Not surprisingly, veterans who had young children during the time they served on active duty are more likely than non-parents to say they have experienced strains in family relations since leaving the military (57% vs. 43%).

Emotional Trauma and Its Aftermath

The challenges veterans face upon returning to civilian life are often linked to experiences they had in combat. Among post-9/11 combat veterans, more than half (52%) say that during their military service, they had experiences that were emotionally traumatic or distressing. Noncombat veterans are less likely to report having these types of experiences, though they are not immune. Among post-9/11 veterans who did not serve in combat, 30% say they had traumatic or distressing experiences over the course of their military service.

The challenges veterans face upon returning to civilian life are often linked to experiences they had in combat. Among post-9/11 combat veterans, more than half (52%) say that during their military service, they had experiences that were emotionally traumatic or distressing. Noncombat veterans are less likely to report having these types of experiences, though they are not immune. Among post-9/11 veterans who did not serve in combat, 30% say they had traumatic or distressing experiences over the course of their military service.

Certain characteristics of war cut across generations and military eras, and trauma is one of them. Veterans who served in combat prior to 9/11 are nearly as likely as post-9/11 veterans to report that they had traumatic or distressing experiences during their military service (45%). Among pre-9/11 veterans who did not serve in combat, only one-in-five (19%) say they had these types of experiences.

The challenge for many veterans is dealing with the aftereffects of these experiences. Among all post-9/11 veterans who report having had traumatic experiences during their time in the military, more than seven-in-ten (72%) say they have had flashbacks, repeated distressing memories or recurring dreams of those incidents. Among post-9/11 combat veterans, the share is slightly higher—75% of those who say they had traumatic experiences while they were in the service also say they’ve had flashbacks or nightmares related to those incidents. The experience has been similar for veterans who came before them. Among pre-9/11 combat veterans who had traumatic experiences in the military, 69% suffered from flashbacks, distressing memories or recurring dreams.

Noncombat veterans don’t seem to relive their traumatic experiences to nearly the same extent as combat veterans. Among all noncombat veterans who had emotionally traumatic experiences, only 32% report having flashbacks, repeated memories or recurring dreams.

Noncombat veterans don’t seem to relive their traumatic experiences to nearly the same extent as combat veterans. Among all noncombat veterans who had emotionally traumatic experiences, only 32% report having flashbacks, repeated memories or recurring dreams.

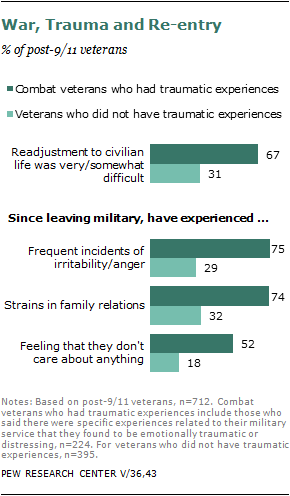

There is a strong link between traumatic wartime experiences and difficulties readjusting to civilian life. Post-9/11 combat veterans who had these types of experiences report having had a much more difficult time transitioning to civilian life, and many say they have faced specific challenges in their day-to-day lives since leaving the military.

Two-thirds (67%) of post-9/11 combat veterans who had traumatic experiences say their readjustment to civilian life after leaving the military was difficult (with 25% describing it as very difficult). Among veterans who did not have these types of experiences, only three-in-ten (31%) say their re-entry to civilian life was difficult.

Similarly, post-9/11 combat veterans who lived through traumatic events during their service are more than twice as likely as veterans who did not have traumatic experiences to say they have suffered from frequent incidents of irritability or anger (75% vs. 29%), strains in family relations (74% vs. 32%), and feelings of despondence and hopelessness (52% vs. 18%).

Post-Traumatic Stress

Some of the specific challenges veterans face after leaving the military—flashbacks, nightmares, outbursts of anger, feelings of hopelessness—are often associated with post-traumatic stress (PTS). Among the post-9/11 veterans included in this survey, more than one-third (37%) say—regardless of whether they have been formally diagnosed—that they think they have suffered from PTS as a result of their experiences in the military. And nearly six-in-ten (58%) say they knew and served with someone who suffered from PTS.

Some of the specific challenges veterans face after leaving the military—flashbacks, nightmares, outbursts of anger, feelings of hopelessness—are often associated with post-traumatic stress (PTS). Among the post-9/11 veterans included in this survey, more than one-third (37%) say—regardless of whether they have been formally diagnosed—that they think they have suffered from PTS as a result of their experiences in the military. And nearly six-in-ten (58%) say they knew and served with someone who suffered from PTS.

Among combat veterans who have served since 9/11, roughly half (49%) say they have likely suffered from PTS and 70% say they served with someone who had PTS.

Post-9/11 veterans are much more likely than those who served prior to 9/11 to have exposure to PTS. This may be in part because more post-9/11 veterans served in combat and in part because there is greater awareness about PTS now than in previous eras. Among veterans from the pre-9/11 era, only 16% say they have suffered from PTS, and 35% say they knew someone who did.

Post-traumatic stress affects veterans from all walks of life. Among post-9/11 veterans, roughly equivalent shares of men and women, whites, blacks and Hispanics, young and old say they have likely suffered from PTS. That said, certain segments of the military report much higher rates of PTS than others. Fully half (51%) of all Army veterans surveyed from the post-9/11 era say they have suffered from PTS. This compares with roughly one-in-five Air Force and Navy veterans. Among veterans of the Marines, 39% say they have suffered from PTS.

Service rank also seems to have an impact on rates of PTS. Among post-9/11 veterans, those who served as commissioned officers are much less likely than others to say they have suffered from PTS (22%). Those who were NCOs are among the most likely to say they’ve had PTS (46%). Veterans who were rank-and-file enlisted personnel are slightly less likely than NCOs to say they have suffered from PTS (35%), though the difference is not statistically significant.

PTS affects more than emotional health. It can have a significant impact on a veteran’s quality of life more generally. Among post-9/11 veterans who say they’ve suffered from PTS as a result of their military experience, only 15% say they are very happy with their life overall. This compares with 37% of veterans who have not suffered from PTS.

PTS affects more than emotional health. It can have a significant impact on a veteran’s quality of life more generally. Among post-9/11 veterans who say they’ve suffered from PTS as a result of their military experience, only 15% say they are very happy with their life overall. This compares with 37% of veterans who have not suffered from PTS.

Post-9/11 veterans with PTS are also less likely than others to be satisfied with their family life. While 52% of veterans who have had PTS say they are very satisfied with their family life, 71% of those who have not had PTS say the same. Veterans with PTS are also more downbeat about their financial situations: 48% say they are satisfied with their personal financial situation, compared with 64% who have not had PTS.

Perhaps the most dramatic gap is on veterans’ ratings of their overall health. Only 4% of veterans who have suffered from PTS say they are currently in excellent health. This compares with 39% of their fellow veterans who have not faced this challenge.

If there is any good news in this part of the story, it may be that today’s veterans say they felt comfortable seeking help if and when they needed it. Nearly seven-in-ten post-9/11 veterans (69%) say their superiors made them and others who served with them feel comfortable about seeking help with emotional issues resulting from their military service. Fewer than one-in-four (23%) say they were made to feel uncomfortable. This marks a significant break from the past. Only half of pre-9/11 veterans (51%) say their superiors made them feel comfortable seeking help for emotional issues.

Among post-9/11 veterans the level of comfort with seeking help for emotional issues is largely consistent across rank and service branch. However, those who say they have actually suffered from PTS are among the least likely to say their superiors made them feel comfortable seeking help if they needed it (62% vs. 75% among those who have not suffered from PTS).

Among post-9/11 veterans the level of comfort with seeking help for emotional issues is largely consistent across rank and service branch. However, those who say they have actually suffered from PTS are among the least likely to say their superiors made them feel comfortable seeking help if they needed it (62% vs. 75% among those who have not suffered from PTS).

The Government’s Role in Re-entry

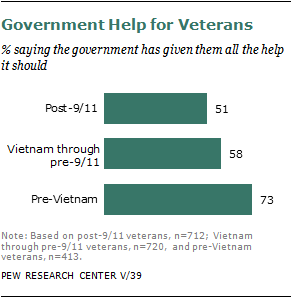

The federal government gets mixed ratings for the role it has played in helping veterans readjust to civilian life and in providing support and services to veterans in need. Some 51% of post-9/11 veterans say the government has given them personally all the help they think it should, while 47% say it has not.

Veterans who served in the pre-9/11 era, particularly those who served prior to the Vietnam War, have a more positive view of the role government has played in their lives. Among veterans from the pre-Vietnam era, 73% say government has given them all the help it should. Among those who served during Vietnam and prior to 9/11, 58% share this view.

Veterans who served in the pre-9/11 era, particularly those who served prior to the Vietnam War, have a more positive view of the role government has played in their lives. Among veterans from the pre-Vietnam era, 73% say government has given them all the help it should. Among those who served during Vietnam and prior to 9/11, 58% share this view.

Among post-9/11 veterans, commissioned officers give the government higher ratings than do NCOs or other enlisted personnel. Two-thirds of commissioned officers (66%) say the government has done all it should for them. Only 43% of NCOs and 52% of rank-in-file enlisted personnel agree with this assessment.

Whether or not a veteran served in combat does not have a significant influence on that individual’s overall rating of the job government has done in supporting veterans. Some 48% of post-9/11 combat veterans and 56% of noncombat veterans say the government has done all it should to help them personally. However, what a veteran experienced in combat does seem to affect evaluations of government. Among post-9/11 veterans who say they have suffered from PTS as a result of their experiences in the military, only 30% say the government has done all it should to help them. Among those who have not suffered from PTS, 63% give the government positive marks.

Respondents were also asked to rate the job the Veterans Administration (VA) is doing today to meet the needs of military veterans.16 Among all post-9/11 veterans, 12% say the VA is doing an excellent job in this regard, and 39% say it’s doing a good job. More than one-third (35%) say the VA is doing only a fair job meeting the needs of today’s veterans, and 9% say it’s doing a poor job. The ratings the VA receives from pre-9/11 veterans are not significantly different.

Respondents were also asked to rate the job the Veterans Administration (VA) is doing today to meet the needs of military veterans.16 Among all post-9/11 veterans, 12% say the VA is doing an excellent job in this regard, and 39% say it’s doing a good job. More than one-third (35%) say the VA is doing only a fair job meeting the needs of today’s veterans, and 9% say it’s doing a poor job. The ratings the VA receives from pre-9/11 veterans are not significantly different.

Post-9/11 combat veterans who had traumatic experiences during their military service or have suffered from PTS are more critical of the VA. Among those who say they have suffered from PTS, a majority (56%) say the VA is doing only a fair or poor job meeting the needs of today’s veterans, compared with 43% who say it’s doing an excellent or good job. Among those who have not suffered from PTS, 57% give the VA high marks while 37% say it’s doing a fair or poor job.

More than six-in-ten post-9/11 veterans (62%) say they have received benefits from the VA. Those who have served in combat are more likely than those who have not to say they have received VA benefits (68% vs. 54%). Veterans who served prior to 9/11 are somewhat less likely to say they received benefits from the VA (54%).

Among post-9/11 veterans who say they’ve received benefits from the VA, 60% give the agency excellent or good marks for meeting the needs of today’s veterans. The VA receives lower ratings from those who have not received benefits (only 39% rated the agency excellent or good).

Work-Life after the Military

After leaving the military, most veterans still have years if not decades left in their working life.17 Many also pursue more education. Among those under age 30, more than one-third (37%) are full-time students, and 8% go to school part time. Among post-9/11 veterans, noncommissioned officers and rank-and-file enlisted personnel are more likely than commissioned officers to be enrolled in school. This is presumably because commissioned officers already have at least a four-year college degree.

As the national unemployment rate hovers between 9 and 10 percent, the unemployment rate among post-9/11 veterans has been well past that threshold. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that in 2010 the unemployment rate for post-9/11 veterans was 11.5%. This is higher than the jobless rate for veterans from all eras combined (8.7% in 2010) and for non-veterans (9.4%). Unemployment is particularly high among young veterans from the post-9/11 era. According to the BLS, 21.9% of male veterans ages 18-24 from the post-9/11 era were unemployed in 2010. This is not statistically different from the share of male non-veterans in that same age group, 19.7% of who were unemployed in 2010.18

While most veterans acquired certain skills and knowledge in the military, they can also face unique challenges in the civilian job market. Some have physical injuries and disabilities; some carry with them the emotional scars of war. Most post-9/11 veterans say their military experience was useful in preparing them for a job or career. However, only 41% say it was very useful. Post-9/11 veterans who say the military helped prepare them for civilian work are much more likely to be gainfully employed than those who do not believe the military prepared them. Among those who say the military was very helpful in preparing them for a job, 64% are now employed full time. This compares with less than half who say the military was not helpful in preparing them for a civilian career.

Among the post-9/11 veterans included in this survey, employment status differs somewhat across military rank. While 74% of retired commissioned officers are employed full time, only 57% of NCOs and 51% of rank-and-file enlisted personnel are working full time.

Post-9/11 veterans who carry with them emotional scars from their service are among the least likely to be working full time. Among those who say they had traumatic experiences in the military, only 48% are working full time. This compares with 62% of those who did not have these types of experiences.