Overview

The role of fathers in the modern American family is changing in important and countervailing ways. Fathers who live with their children have become more intensely involved in their lives, spending more time with them and taking part in a greater variety of activities. However, the share of fathers who are residing with their children has fallen significantly in the past half century.

In 1960, only 11% of children in the U.S. lived apart from their fathers. By 2010, that share had risen to 27%. The share of minor children living apart from their mothers increased only modestly, from 4% in 1960 to 8% in 2010.

In 1960, only 11% of children in the U.S. lived apart from their fathers. By 2010, that share had risen to 27%. The share of minor children living apart from their mothers increased only modestly, from 4% in 1960 to 8% in 2010.

According to a new Pew Research Center analysis of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), more than one-in-four fathers with children 18 or younger now live apart from their children—with 11% living apart from some of their children and 16% living apart from all of their children.1

Fathers’ living arrangements are strongly correlated with race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status as measured by educational attainment. Black fathers are more than twice as likely as white fathers to live apart from their children (44% vs. 21%), while Hispanic fathers fall in the middle (35%). Among fathers who never completed high school, 40% live apart from their children. This compares with only 7% of fathers who graduated from college.

Almost all fathers who live with their children take an active role in their day-to-day lives through activities such as sharing meals, helping with homework, and playing. Fathers who live apart from their children are much less likely to be involved in these types of activities. Many compensate by communicating with their children through email or by phone: four-in-ten nonresident dads say they are in touch with their children several times a week. At the same time, however, nearly one-third of fathers who do not live with their children say they talk or exchange email with them less than once a month. Similarly, one-in-five absent fathers say they visit their children more than once a week, but an even greater share (27%) say they have not seen their children at all in the past year.

The analysis of the NSFG was paired with a new Pew Research survey of attitudes toward fatherhood that finds a strong majority of the public saying children need a father in the home. Fully 69% say having a father in the home is essential to a child’s happiness. Only a slightly higher share (74%) says the same about having a mother in the home.

The Pew Research survey also finds that most fathers (63%) say being a dad is harder today than it was a generation ago. And the public gives today’s dads mixed grades for the job they are doing as parents. Only about one-in-four adults say fathers today are doing a better job as parents than their own fathers did. Roughly one-third (34%) say they are doing a worse job, and 40% say they are doing about the same job. Dads themselves have similar opinions: 26% say today’s fathers are doing a better job than their own fathers did. However, when asked about the job they are doing raising their own children, 47% say they’re doing a better job than their own dad did; while 3% say they’re doing a worse job.

More Time Spent, But Fewer Fathers in the Home

The changing role of fathers in the home can be measured in different ways. One approach is to look at the amount of time fathers spend caring for their children. Changing trends in time use data help illustrate the extent to which fathers who reside with their children have become more involved in their lives over time. In 1965, married fathers with children under age 18 living in their household spent an average of 2.6 hours per week caring for those children. Fathers’ time spent caring for their children rose gradually over the next two decades—to 2.7 hours per week in 1975 and 3 hours per week in 1985. From 1985 to 2000, the amount of time married fathers spent with their children more than doubled – to 6.5 hours in 2000. From 1965 to 2000, married mothers consistently logged more time than married fathers caring for their minor children, though the gap between mothers and fathers in time spent on child care narrowed significantly.

The changing role of fathers in the home can be measured in different ways. One approach is to look at the amount of time fathers spend caring for their children. Changing trends in time use data help illustrate the extent to which fathers who reside with their children have become more involved in their lives over time. In 1965, married fathers with children under age 18 living in their household spent an average of 2.6 hours per week caring for those children. Fathers’ time spent caring for their children rose gradually over the next two decades—to 2.7 hours per week in 1975 and 3 hours per week in 1985. From 1985 to 2000, the amount of time married fathers spent with their children more than doubled – to 6.5 hours in 2000. From 1965 to 2000, married mothers consistently logged more time than married fathers caring for their minor children, though the gap between mothers and fathers in time spent on child care narrowed significantly.

Alongside this trend toward more time spent with children is a trend toward more children living apart from their fathers. Declining marriage rates and increases in out-of-wedlock births and multi-partner fertility have given rise to complicated family structures and have increased the likelihood that fathers will not reside with all of their children.2 According to the NSFG, nearly half of all fathers (46%) now report that at least one of their children was born out of wedlock, and 31% report that all of their children were born out of wedlock. In addition, some 17% of men with biological children have fathered those children with more than one woman.3

Living Apart from the Kids

What is life like for fathers who live apart from their children? As would be expected, there is a wide variety of experiences. Some fathers are highly involved with their children, in spite of the fact that they do not live together. Others have little or no contact with their children. Roughly one-in-five fathers who live apart from their children say they visit with them more than once a week, and an additional 29% see their children at least once a month. For 21% of these fathers, the visits take place several times a year. And for 27% there are no visits at all.4

What is life like for fathers who live apart from their children? As would be expected, there is a wide variety of experiences. Some fathers are highly involved with their children, in spite of the fact that they do not live together. Others have little or no contact with their children. Roughly one-in-five fathers who live apart from their children say they visit with them more than once a week, and an additional 29% see their children at least once a month. For 21% of these fathers, the visits take place several times a year. And for 27% there are no visits at all.4

Communicating by phone or email is more prevalent than face-to-face contact. Among fathers who live apart from their minor children, 41% say they are in touch with them via phone or email several times a week; 28% say they communicate at least monthly. Still, a sizable minority (31%) say they talk on the phone or email with their children less than once a month.

Fathers, Children and Day-to-Day Activities

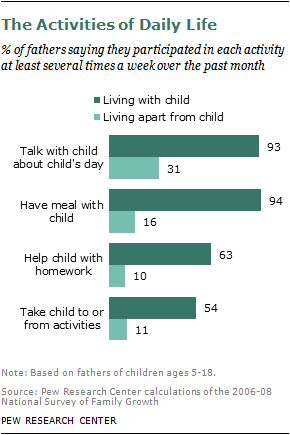

When it comes to spending time with a child, being in the same home makes a huge difference. More than nine-in-ten fathers who live with their children at least part of the time report that they shared a meal with their child or talked with their child about the child’s day almost daily over the past several weeks. Nearly two-thirds (63%) say they helped their child with homework or checked on their homework at least several times a week, and 54% say they took their child to or from activities several times a week or more.

When it comes to spending time with a child, being in the same home makes a huge difference. More than nine-in-ten fathers who live with their children at least part of the time report that they shared a meal with their child or talked with their child about the child’s day almost daily over the past several weeks. Nearly two-thirds (63%) say they helped their child with homework or checked on their homework at least several times a week, and 54% say they took their child to or from activities several times a week or more.

By comparison, relatively few fathers who live apart from their children report taking part in these activities. Three-in-ten (31%) say they talked with their child about his or her day several times a week or more. Only 16% say they had a meal with their child several times a week over the past month. One-in-ten helped out with homework several times a week or more, and 11% took a child to or from activities.

Are You a Good Father?

A father’s presence or absence in the home is closely related to how he evaluates the job he is doing as a parent. Among fathers who live with their children at least part of the time, nearly nine-in-ten say they are doing a very good (44%) or good (44%) job as fathers to those children. An additional 11% classify themselves as okay fathers, and less than 1% say they are doing a bad or not very good job as a father.

Fathers who do not live with their children rate themselves much more negatively. Only 19% say they are doing a very good job as fathers to the children they live apart from, and 30% say they are doing a good job. One-in-four say they are doing an okay job, while nearly as many describe their parenting as not very good (13%) or bad (9%).

About the Report

This report is based mainly on Pew Research Center analysis of the 2006-08 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). The NSFG gathers information on family life, marriage and divorce, pregnancy, infertility, and men’s and women’s health. The survey is an ongoing initiative of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data used for this report are drawn from Cycle 7, which was a continuous survey conducted from June 2006 to June 2010. Data from 2006-08 is based on interviews with 13,495 respondents ages 15-44; 7,356 were female and 6,139 male. Unless otherwise noted, all findings in this report are from the NSFG.

The results of a new Pew Research Center survey complement the findings from the NSFG. The Pew Research survey was conducted by landline and cellular telephone May 26-29 and June 2-5, 2011, among a nationally representative sample of 2,006 adults living in the continental United States.

The charts for this report were prepared by Daniel Dockterman. Paul Taylor, director of the Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends project, provided editorial guidance. Wendy Wang provided valuable comments and research assistance. Daniel Dockterman and Wendy Wang did the number checking, and Marcia Kramer copy-edited the report.

The report is divided into three sections: (1) Overview; (2) Living Arrangements and Father Involvement; (3) Attitudes about Fatherhood. A detailed methodology and topline can be found in the appendices.

Notes on Terminology

The definition of “father” varies from question to question in the report, in order to reflect the wording and structure of the NSFG.

- For questions regarding marital status at birth, and whether a father is living with the mother of all of his biological children: “Fathers” are limited to men who have biological children.

- For questions regarding co-residence and time spent with children: “Fathers” refer to men with children 18 or younger. For co-residers, “fathers” include men with biological children, adopted children, stepchildren, or those who are living with their partner’s children. For non-co-residers, “fathers” are based on men with biological or adopted children only.

- For NSFG attitude questions and questions regarding childlessness, “father” includes any man with biological or adopted children. Conversely, childless men have no biological or adopted children.

Any father who says that his child lives full time or part time in his household is considered a “co-resident” father. Any father who does not live with his biological or adopted children is a “non-co-resident” father. Part-time co-residence is self-identified by the father.

The terms “whites,” “blacks” and “African Americans” are used to refer to the non-Hispanic components of their populations. Hispanics can be of any race.

Other Key Findings

- Men have a strong desire to be fathers… Overall, 87% of males ages 15-44 who have no children say that they want to have children at some point. Among childless men between the ages of 40-44, a narrow majority (51%) still want children.

- …But most say you don’t need children to be happy. Men who do not have children reject the idea that people can’t be happy unless they have children. Only 8% of childless men agree with this statement, and even among fathers, only a small minority (14%) agree that children are necessary in order to be happy.

- Most say being a father is harder today than it was a generation ago… Among all adults, 57% say it is more difficult to be a father today than it was 20 or 30 years ago. Only 9% say being a father is easier today, and 32% say it’s about the same. Among dads themselves, 63% say the job is harder now.

- …But there is no consensus on whether today’s fathers are more involved. The public is evenly split over whether today’s fathers play a greater role or a lesser role in their children’s lives compared with dads 20 or 30 years ago. While 46% say fathers play a greater role now, 45% say they play less of a role now.