The nation’s college and university presidents give a mixed report card to the higher education system they lead, according to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in association with the Chronicle of Higher Education. On questions about the general direction of U.S. higher education, its rank among world systems, its affordability and its value, most college and university presidents do not give top marks. A notable share gives poor grades.

The nation’s college and university presidents give a mixed report card to the higher education system they lead, according to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in association with the Chronicle of Higher Education. On questions about the general direction of U.S. higher education, its rank among world systems, its affordability and its value, most college and university presidents do not give top marks. A notable share gives poor grades.

The online survey was taken from March 15 to April 24, 2011, among the presidents of 1,055 two-year and four-year private, public and for-profit colleges and universities.

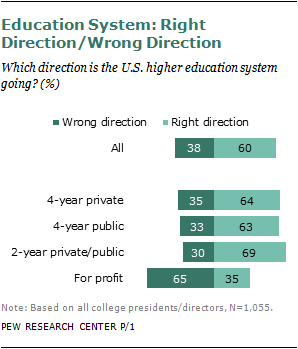

It finds that a sizable minority of respondents—38%—say the U.S. higher education system is headed in the wrong direction. Only one-in-five (19%) say it is the best in the world today, and an even smaller share (7%) believe it will be so in a decade.

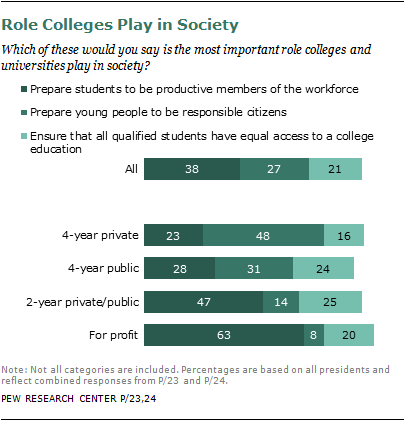

The survey reveals a range of views about the main role of higher education in society. A plurality of 38% of presidents say that role is to prepare students to be productive members of the workforce,9 while 27% say it is to prepare students to be responsible citizens and 21% say it is to ensure that all qualified students have equal access to a college education.

When asked about higher education’s most important role in the lives of students, the presidents are evenly split between the 50% who say it is to provide education for intellectual or personal growth and the 48% who emphasize work- and career-oriented goals.10

On a question about the cost of college, some 57% of college presidents say most people cannot afford a college education today, a smaller share than the proportion of the general public (75%) that says the same. And on a question about the value that higher education provides for the money spent by students and their families, three-quarters say the value is good (59%) or excellent (17%).

The presidents also were asked about a range of issues at the center of ongoing debates about higher education—including student quality, the role of athletic programs and the system of faculty tenure. Other survey questions focused on how their institutions should be judged by students and the public, as well as what they consider important in deciding whether a student should be admitted to college.

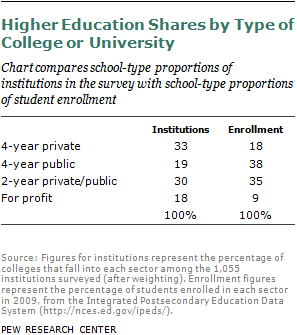

The presidents surveyed represent all sectors of U.S. higher education, and their responses were weighted to reflect the share of institutions in the survey that are private four-year colleges and universities, public four-year colleges and universities, two-year colleges (overwhelmingly public) and for-profit institutions.11 This breakdown is somewhat different from what it would have been if responses had been weighted by student enrollment in each sector. For example, four-year public colleges account for 19% of the survey universe, but 38% of total enrollment.

The presidents surveyed represent all sectors of U.S. higher education, and their responses were weighted to reflect the share of institutions in the survey that are private four-year colleges and universities, public four-year colleges and universities, two-year colleges (overwhelmingly public) and for-profit institutions.11 This breakdown is somewhat different from what it would have been if responses had been weighted by student enrollment in each sector. For example, four-year public colleges account for 19% of the survey universe, but 38% of total enrollment.

On some (but not all) of the survey questions, there are differences in responses among presidents of different types of institutions. Generally, leaders of the growing for-profit sector are the most downbeat about the higher education system and its students. And on some questions, presidents of four-year public universities—many of them facing reduced financial support from budget-strapped state governments—are notably more negative than their counterparts at private universities.

State of Higher Education

Nearly four-in-ten college and university presidents (38%) say the U.S. higher education system generally is headed in the wrong direction; 60% say it is headed in the right direction. There are differences on this question among leaders of public, private and for-profit institutions.

Presidents of for-profit schools, a small but fast-growing sector of the U.S. higher education system (it makes up 18% of all institutions in the survey), are the most negative. Two-thirds (65%) say the higher education system is headed in the wrong direction, while majorities of presidents of four-year and two-year not-for-profit institutions say the system is headed in the right direction.

Still, even among presidents of public and private institutions, a notable share say higher education is headed in the wrong direction. This includes 35% of the presidents of four-year private institutions, 33% of the presidents of four-year public institutions and 30% of the leaders of two-year colleges.

Still, even among presidents of public and private institutions, a notable share say higher education is headed in the wrong direction. This includes 35% of the presidents of four-year private institutions, 33% of the presidents of four-year public institutions and 30% of the leaders of two-year colleges.

As will be seen later in this chapter, presidents who say higher education is headed in the wrong direction are also more likely to have gloomier views about the quality of college students and the value colleges provide to students for the money they and their families spend.

Best in the World?

Only one-in-five presidents (19%) say the U.S. higher education system is the best in the world. A narrow majority—51%—say it is one of the best, and an additional 17% say it is above average. One-in-ten (10%) say it is average, and 1% say it is below average. “One of the best” is the majority choice among presidents from all sectors except for-profit institutions, where it is the plurality choice. As for the future, presidents are even less optimistic: Only 7% predict that the U.S. education system will be the best in the world a decade from now.

Only one-in-five presidents (19%) say the U.S. higher education system is the best in the world. A narrow majority—51%—say it is one of the best, and an additional 17% say it is above average. One-in-ten (10%) say it is average, and 1% say it is below average. “One of the best” is the majority choice among presidents from all sectors except for-profit institutions, where it is the plurality choice. As for the future, presidents are even less optimistic: Only 7% predict that the U.S. education system will be the best in the world a decade from now.

Presidents of for-profit schools (8%) and of two-year schools (13%) are less likely than other presidents to say the U.S. system is the best in the world. Among presidents of four-year

schools, 25% of the presidents of private institutions and 30% of the presidents of public institutions say the U.S. system is the world’s best.

Fully 23% of for-profit college and university presidents and 14% of two-year college presidents say the U.S. system is just average. Only 3% of the presidents of four-year public or private institutions say so.

Among presidents of four-year and two-year public and private institutions, the majority or plurality predicts the U.S. system will be the best or one of the best in a decade. Among presidents of for-profit schools, only 32% say it will be the best or one of the best in the world.

Again, presidents of for-profit and two-year colleges are more likely than presidents of private and public four-year institutions to predict that the U.S. system will be average or below average. Responses of more than a third (34%) of for-profit presidents fall into those categories, compared with 21% of two-year college presidents, 9% of four-year private school presidents and 12% of four-year public school presidents.

Obama Goal

President Obama has set a goal that by 2020 the United States should have the world’s highest share of young adults (ages 25 to 34) with college degrees or two-year certificates. Most college presidents (in all categories of institution) say achieving that goal is not likely.

President Obama has set a goal that by 2020 the United States should have the world’s highest share of young adults (ages 25 to 34) with college degrees or two-year certificates. Most college presidents (in all categories of institution) say achieving that goal is not likely.

In his 2009 State of the Union speech, Obama cited the growing number of occupations that require more than a high school diploma. The nation, he said, “needs and values the talents of every American. That is why we will provide the support necessary for you to complete college and meet a new goal: by 2020, America will once again have the highest proportion of college graduates in the world.”

According to Current Population Survey figures cited by the U.S. Department of Education, 42% of 25- to 34-year-olds had completed at least an associate degree in 2010. However, “to reclaim America’s lead will likely require 60% of young adults to earn an associate or baccalaureate degree by 2020,” according to the department.12 As the accompanying table shows, the United States trails some other developed nations by this metric.

According to Current Population Survey figures cited by the U.S. Department of Education, 42% of 25- to 34-year-olds had completed at least an associate degree in 2010. However, “to reclaim America’s lead will likely require 60% of young adults to earn an associate or baccalaureate degree by 2020,” according to the department.12 As the accompanying table shows, the United States trails some other developed nations by this metric.

Among all college presidents, 50% say attaining Obama’s goal of having the world’s largest share of college graduates is “not too likely” and 14% say it is “not at all likely.” Only 3% say it is “very likely” the U.S. will meet this standard, and 32% say it is “somewhat likely.” Among presidents of all types of institutions – for profit or non-profit, or two-year or four-year schools—a majority are skeptical about meeting this goal.

Role in Society

Queried about the most important role of higher education in society, presidents split their votes between preparing students to be productive members of the workforce and preparing them to be responsible citizens. Among all presidents, 38% say the workforce role is most important and 27% say the citizen role is most important. Ensuring that all qualified students have equal access to higher education is deemed the most important role by 21%.

Queried about the most important role of higher education in society, presidents split their votes between preparing students to be productive members of the workforce and preparing them to be responsible citizens. Among all presidents, 38% say the workforce role is most important and 27% say the citizen role is most important. Ensuring that all qualified students have equal access to higher education is deemed the most important role by 21%.

There is wide variation by sector on this question. The share of college presidents choosing workforce development as the most important role ranges from 23% of private four-year college presidents to 63% of for-profit college presidents (the only group in which a majority chooses this role as most important).

The role of preparing students to be responsible citizens is chosen as most important by 48% of private four-year college and university presidents and 8% of for-profit college presidents.

Presidents of schools with religious affiliations are more likely than other presidents to choose the role of preparing students to be responsible citizens (57% to 20%). They are notably less likely than other presidents to say the most important role of higher education is to prepare students to be productive members of the workforce (17% to 43%).

Specific Roles

Presidents also were asked to evaluate seven specific roles for higher education in society on a scale ranging from “not at all important” to “very important.” A majority say it is very important for higher education to conduct research to solve national problems (54%), as well as to prepare students for the workforce (74%) or to be responsible citizens (73%) and to ensure equal access to higher education (72%).

Presidents also were asked to evaluate seven specific roles for higher education in society on a scale ranging from “not at all important” to “very important.” A majority say it is very important for higher education to conduct research to solve national problems (54%), as well as to prepare students for the workforce (74%) or to be responsible citizens (73%) and to ensure equal access to higher education (72%).

Half (52%) say it is very important for institutions to contribute to the economic development of their region or locality. Providing continuing education for adults of all ages is deemed very important by 37% of presidents, and 17% say the same about providing cultural events and enrichment to the surrounding community.

There are notable differences among education sectors on these measures. Conducting research and training responsible citizens both are very important to most public and private college presidents, but less so among for-profit college presidents.

Most public and private college and university presidents agree that it is very important for institutions to conduct medical, scientific, social and other research to help solve national problems, but only 30% of for-profit college presidents say so. For-profit college presidents and two-year college presidents are more likely than presidents of four-year public and private institutions to say that developing productive members of the workforce is very important.

On the question of contributing to the economic development of their community or region, most presidents of public four-year institutions and of two-year colleges (the majority of them public institutions) say this is very important, but only a minority of the heads of private four-year schools and for-profit institutions say the same.

Sponsoring cultural events and enrichment for the surrounding community is notably less important to for-profit college presidents than to the heads of other institutions. Providing continuing education is more important to two-year college presidents than to four-year college presidents.

Value to the Economy

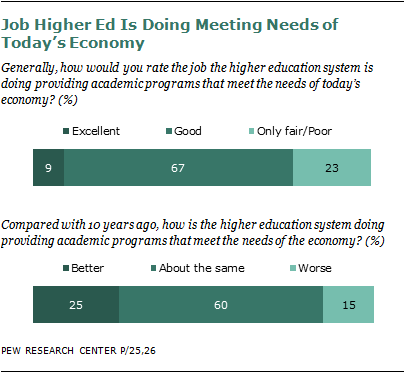

Given the importance that many presidents place on training students to be productive members of the workforce, how good a job do the presidents think higher education is doing in providing academic programs that meet the needs of today’s economy? Most college and university presidents give a good rating, but few give an excellent rating (9%). Most say this level of performance has not changed in the last decade.

Given the importance that many presidents place on training students to be productive members of the workforce, how good a job do the presidents think higher education is doing in providing academic programs that meet the needs of today’s economy? Most college and university presidents give a good rating, but few give an excellent rating (9%). Most say this level of performance has not changed in the last decade.

On this question, there is a notable difference between presidents of public and private and for-profit institutions. At least eight-in-ten presidents of private or public institutions, be they four-year or two-year, give an excellent or good rating to higher education’s performance in meeting today’s economic needs. However, only half the presidents of for-profit institutions rate higher education as doing an excellent (3%) or good (47%) job on this front.

On the question of whether the relevance of academic programs to the needs of the economy has grown in the past decade, most college and university presidents in all sectors of institution say there has been no change. Overall, 60% say the performance in this area is the same as it was a decade ago, 25% say it is better than 10 years ago and 15% say it is worse.

However, presidents of four-year public institutions and two-year institutions are more likely than the heads of private and for-profit schools to say the situation has improved in the past decade. Presidents of for-profit institutions (23%) are more likely than heads of four-year public or private schools to say the performance has worsened.

Role in Lives of Students

There is a long-running debate in the higher education world over whether its main role in the lives of students should tilt more toward personal and intellectual growth or toward preparation for the world of work. In this survey, presidents were offered a range of choices from both realms.

There is a long-running debate in the higher education world over whether its main role in the lives of students should tilt more toward personal and intellectual growth or toward preparation for the world of work. In this survey, presidents were offered a range of choices from both realms.

Asked to choose among five options for which role is most important in the lives of students, a plurality (44%) chooses providing a broad-based education, followed by general skills and knowledge for the working world (27%) and training for a specific career or profession (13%). Helping students improve earnings potential (8%) and promoting personal growth and maturity (6%) were chosen by a smaller share.

Combined, the two intellectual-personal roles are chosen by 50% of presidents and the work-oriented goals are chosen by 48% of presidents.

Presidents also were asked to assess the importance of each role, from “not at all important” to “very important.” More than eight-in-ten say it is very important to provide a broad-based education that promotes intellectual growth (81%) and to provide skills and knowledge that will be of general value in the working world (86%). Three-quarters (75%) say it is very important to promote personal growth and maturity. More than half (58%) say it is very important to help students improve their future earnings potential, and half (50%) say it is very important to provide training for a specific career or profession.

Differences by Type of President

However, there are notable differences among different sectors of college and university presidents who select each goal, which reflects differences in each sector’s own mission. About two-thirds (64%) of the combined presidents of four-year public and private institutions say a broad-based education is the most important goal. Less than a third (29%) of the presidents of two-year colleges say so, as do only 13% of the heads of for-profit institutions. The goal chosen most often by two-year college presidents as most important is providing skills and knowledge of general value in the working world (37%). The heads of for-profit schools are equally likely to choose general preparation for the working world (33%) and training for a specific career or profession (32%) as most important.

Among presidents of schools with a religious affiliation, 64% say a broad-based education is most important, compared with 39% of the presidents of nonaffiliated schools.

Costs and Benefits

There is growing public concern about whether a college education is affordable for most Americans. As seen earlier in this report, although most college presidents (57%) say college is not affordable for most people, an even higher share of the general public says so. Four-in-ten (42%) presidents say it is affordable.

There is growing public concern about whether a college education is affordable for most Americans. As seen earlier in this report, although most college presidents (57%) say college is not affordable for most people, an even higher share of the general public says so. Four-in-ten (42%) presidents say it is affordable.

Looking at differences by sector, 65% of the presidents of two-year colleges say higher education is not affordable for most people, compared with 35% who say it is. Among presidents of four-year private colleges, 44% say that college is affordable and 56% say it is not. Among presidents of four-year public institutions, 53% say that college is affordable and 47% say it is not. Among presidents of for-profit schools, 42% say that college is affordable and 58% say it is not.13

Answers also vary by whether the share of students receiving financial aid has risen at the president’s institution. Among presidents of schools where the share of students receiving financial aid has not changed in the past decade, 53% say college is affordable for most people. Among presidents of schools where more students receive financial aid than did so a decade ago, 60% say most people cannot afford college costs. There are no significant differences between presidents of institutions by the share of students receiving financial aid, typical level of student debt or amount of tuition and fee increases in recent years.

Overall, college presidents are quite accurate in estimating average student debt. Among four-year college graduates, the average student with outstanding debt owes more than $23,000.14 As a group, the median estimate among presidents of four-year institutions is $22,599.

Good Value

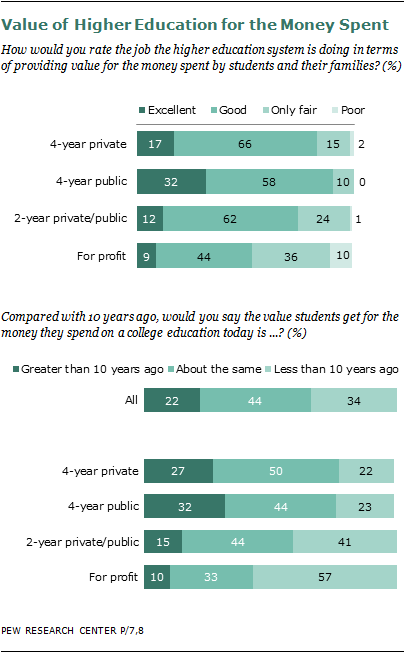

Most presidents say today’s higher education system provides good (59%) or excellent (17%) value for the money spent by students and their families. A smaller share says the system provides only fair (21%) or poor value (3%).

Most presidents say today’s higher education system provides good (59%) or excellent (17%) value for the money spent by students and their families. A smaller share says the system provides only fair (21%) or poor value (3%).

Presidents of four-year public colleges are most inclined to say education offers excellent value—a third (32%) do, notably higher than the share of their counterparts who head private four-year colleges (17%), two-year colleges (12%) or for-profit colleges (9%).

As with other questions, presidents of for-profit schools give less favorable assessments. Nearly half (46%) say college offers only fair or poor value, compared with 25% of two-year college presidents and even smaller shares of four-year college presidents.

Most college and university presidents say higher education offers at least the same value (44%) or more value (22%) than a decade ago, but this overall rating obscures differences by sector. Presidents at four-year private (27%) and public (32%) institutions are more inclined than presidents of two-year (15%) or for-profit schools (10%) to say higher education offers greater value than a decade ago. Presidents of two-year (41%) and for-profit (57%) schools are more inclined than the presidents of four-year private (22%) or public institutions (23%) to say it offers less value.

Who Should Pay?

Generally speaking, most college and university presidents (63%) say that students or their families should pay the largest share of tuition, room and board and other college expenses at their institution. Some 22% say state government should do so, 10% say the federal government should pay the most and 2% list other preferred sources.

Generally speaking, most college and university presidents (63%) say that students or their families should pay the largest share of tuition, room and board and other college expenses at their institution. Some 22% say state government should do so, 10% say the federal government should pay the most and 2% list other preferred sources.

The responses on this question vary by sector, with more emphasis placed on government funding by the presidents of four-year public colleges and universities as well as two-year colleges (most of whom head public institutions).

Among presidents of private four-year colleges, 84% say students and their families should pay the most, as do 78% of for-profit college presidents. Among four-year public college and university presidents, 41% say students or their families and 50% say state government. Among two-year college presidents, 46% say students or their families and 39% say state government.

Assessing Students and Colleges

What are important factors in attracting students? When given a list of seven potential factors, 50% of presidents say the strength of the academic programs is the most important one in competing with other institutions to attract students. The academic program is the majority choice among presidents of four-year private schools and four-year public schools (57% each) and is chosen by 50% of the heads of for-profit schools. Among presidents of two-year colleges, a plurality (37%) says so.

What are important factors in attracting students? When given a list of seven potential factors, 50% of presidents say the strength of the academic programs is the most important one in competing with other institutions to attract students. The academic program is the majority choice among presidents of four-year private schools and four-year public schools (57% each) and is chosen by 50% of the heads of for-profit schools. Among presidents of two-year colleges, a plurality (37%) says so.

Markedly smaller shares of all presidents say the most important factors are tuition and mandatory fees (14%), scheduling flexibility (15%), faculty quality (8%), campus location and amenities (7%) and quality of student life (3%). Fewer than 1% choose the athletic program. Presidents of two-year schools (21%) are more likely than other college presidents to say tuition and fees are the most important attraction for students; presidents of two-year (21%) and for-profit (25%) institutions are more likely than presidents of four-year public and private schools to say that flexible scheduling is their most important attraction for students.

Asked about the importance of each factor individually, 84% say that the strength of the academic programs is very important in competing with other institutions to attract students, and a large majority of presidents from all sectors say so. The same is true for faculty quality—80% of all college and university presidents say it is very important in attracting students, and this holds true among all sectors.

Only about half (52%) of college and university presidents say tuition and mandatory fees are a very important factor in attracting students (44% say it is somewhat important). The share saying very important is somewhat higher among two-year college presidents (60%). Similarly, 50% of all presidents say the flexibility of academic scheduling, including online or night classes, is important; that share is notably higher for two-year college presidents (72%) and for-profit college presidents (72%).

Other priorities receive greater emphasis from four-year public and private college and university presidents than from others. The quality of student life is deemed very important by 45% of all college and university presidents, but among 67% of four-year private college presidents and 57% of four-year public college and university presidents. The strength of the athletic program also is more important to four-year college and university presidents; although relatively few label it very important, 48% of four-year private college presidents and 47% of four-year public college presidents say it is somewhat important, in contrast to only 6% of presidents of for-profit colleges, most of which do not have athletic programs.

How Students Should Be Judged in the Admissions Process

What qualities or qualifications should be important in deciding whether to admit a student, assuming that academic performance already has been taken into account? Here, college and university presidents were presented with eight possibilities and asked whether they should be a major, minor or non-factor in college admissions decisions.

What qualities or qualifications should be important in deciding whether to admit a student, assuming that academic performance already has been taken into account? Here, college and university presidents were presented with eight possibilities and asked whether they should be a major, minor or non-factor in college admissions decisions.

There is no majority vote of “major factor” for any of the eight—a student’s socioeconomic status; race or ethnicity; athletic ability; ability to pay full tuition; gender; artistic or other special talent; where the student is from; and whether the student comes from a family in which a parent or other relative attended the same school. In fact, half or more of presidents say that seven of the eight should not be a factor at all. Only “artistic or other special talent” should be a factor in admissions, according to most presidents (60%).

There is some variation by sector in the share of presidents who evaluate some qualities as at least minor factors in admissions decisions. Socioeconomic status, race or ethnicity, and athletic ability should be at least minor factors in admissions among more than half of four-year private and public college presidents, though not among two-year or for-profit college presidents. Race or ethnicity, for example, should be a major (14%) or minor (48%) factor, according to nearly two-thirds of private four-year college presidents; among leaders of public four-year colleges, 13% consider it a major factor and 45% a minor factor. But among leaders of two-year schools, 66% say it should not be a factor, a sentiment shared by 77% of for-profit presidents.

Geography should be a major or minor factor, according to most four-year college and university presidents, but not others. The “legacy” factor of a previous graduate of that institution from the same family is a major or minor factor for 63% of private four-year college presidents, but not a majority among others. The ability to pay full tuition is a major or minor factor for most four-year private college presidents (60%) and half of for-profit college presidents (50%), but not others.

How Should the Public Judge Colleges?

College and university presidents have strong ideas about how they should not be judged. The survey presented them with a list of seven potential indicators for the public to use in assessing the overall quality of a college or university—accreditation, admission rates, graduation rates, national assessment tests or student engagement surveys, peer assessment surveys, popular rankings or standardized test scores.

College and university presidents have strong ideas about how they should not be judged. The survey presented them with a list of seven potential indicators for the public to use in assessing the overall quality of a college or university—accreditation, admission rates, graduation rates, national assessment tests or student engagement surveys, peer assessment surveys, popular rankings or standardized test scores.

Not one gets a majority vote as “very effective.” Accreditation draws a total of 83% when “somewhat effective (43%) and “very effective” (41%) are combined.15 Graduation rates also draw 83% when “somewhat effective” (49%) and “very effective” (34%) are combined.

Those who ranked at least one indicator as “very effective” were asked to choose which is most effective. Among all college presidents, a 35% plurality did not rank any of the indicators as “very effective” or gave no answer. One-in-four choose accreditation, 22% choose graduation rates and 9% select performance on national assessment tests or student-engagement surveys. Presidents of two-year schools are less likely than others to prefer graduation rates (14%), and more likely than presidents of four-year public or private schools to prefer accreditation (35%).

When responses to this question are analyzed only for presidents who choose more than one option as very effective,16 37% choose graduation rates and 28% choose accreditation. An additional 15% choose performance on national assessment tests or student-engagement surveys, and 13% choose peer assessment and reputation surveys.

Contemporary Issues in Higher Education

Student Quality and Workload

When it comes to their students, presidents are somewhat gloomy about their academic preparation for college and the amount of work they do once enrolled, but most believe they are graded fairly.

When it comes to their students, presidents are somewhat gloomy about their academic preparation for college and the amount of work they do once enrolled, but most believe they are graded fairly.

In the 2011 survey, nearly six-in-ten (58%) college and university presidents say public high schools are doing a worse job than a decade ago at preparing students for college. About a third (36%) say there has been no change, and 6% say public high schools are doing a better job.

Most college and university presidents in all categories of institution say public high schools are doing a worse job than they used to do at preparing students for college. Heads of for-profit institutions are even more critical than other presidents. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of the presidents of for-profit institutions say public high school performance has worsened in the past decade, compared with 56% of the presidents of private four-year schools, 52% of the presidents of public four-year institutions and 55% of the presidents of two-year institutions.

The public and private college and university presidents are more likely than the heads of for-profit colleges to say public high school preparation for college is unchanged. Although the numbers are small, presidents of four-year public institutions and two-year colleges (8%) are more likely than the heads of four-year private colleges and universities to say public high school preparation for college has improved.

How hard do today’s college students hit the books? Most college presidents (52%) say

How hard do today’s college students hit the books? Most college presidents (52%) say

they believe their students are studying less than students did a decade ago. Only 7% say students are studying more, and 40% say students are doing about the same amount of studying. The presidents of two-year schools (56%) and for-profit schools (62%) are somewhat more likely to say students are studying less, compared with presidents of four-year private colleges (46%) and four-year public colleges (44%).

Although most (73%) think their students receive grades that are “about right” from faculty members, more than a quarter (27%) of college presidents say students are graded too leniently. The presidents of four-year private colleges (33%) are somewhat more likely than the presidents of four-year public institutions (24%) and two-year institutions (21%) to say students are graded too leniently.

Although most (73%) think their students receive grades that are “about right” from faculty members, more than a quarter (27%) of college presidents say students are graded too leniently. The presidents of four-year private colleges (33%) are somewhat more likely than the presidents of four-year public institutions (24%) and two-year institutions (21%) to say students are graded too leniently.

Only 1% of all presidents say students are graded too stringently.

Athletic Programs

Among heads of colleges with athletic programs, 42% of presidents say the program does not have an impact on their institution’s overall financial picture. About a third (34%) say the athletic program has a positive financial impact and a quarter (24%) says it has a negative financial impact. Only a small number of for-profit schools have athletic programs, so this question applies mainly to other sectors.

The presidents of four-year private institutions (45%) are notably more likely to say the athletic program helps their bottom line than do the presidents of public four-year institutions (28%) or two-year schools (20%). The presidents of two-year schools (32%) are more likely than the heads of four-year private institutions (18%) to say the athletic program hurts their bottom line.

In a 2005 Chronicle survey of four-year college presidents, most (59%) agreed with the general statement, “Big-time college athletics programs are more of a liability than an asset.”

Faculty Tenure

The longtime practice of granting tenure—essentially lifetime job security—to college and university faculty members has become less common in recent years. According to the 2010 Digest of Education Statistics, a rising number and share of faculty members are part timers, who often get hired on annual contracts and whose jobs depend on enrollment in any given year. The share of full-time faculty with tenure declined to 49% in 2009-2010 from 56% in 1993-94.17

The longtime practice of granting tenure—essentially lifetime job security—to college and university faculty members has become less common in recent years. According to the 2010 Digest of Education Statistics, a rising number and share of faculty members are part timers, who often get hired on annual contracts and whose jobs depend on enrollment in any given year. The share of full-time faculty with tenure declined to 49% in 2009-2010 from 56% in 1993-94.17

Advocates say that tenure promotes a long-term commitment to scholarship, institutional governance and student mentoring. But many college administrators say a tenure-heavy faculty leaves them without sufficient staffing flexibility or power to fire unproductive teachers.

Most college and university presidents would prefer that full-time tenured faculty not be the majority at their institution, according to the survey. Only 24% say they would like most faculty members to be full-time and tenured.

On this question, there are big differences by the respondents’ institution type. Among presidents of four-year public colleges, fully half (50%) would prefer that most of their faculty be full-time and tenured, compared with less than a third (30%) of the presidents of private four-year colleges. Among this latter group, a plurality of 40% would prefer that most of their faculty be on long-term contracts.

As might be expected, the presidents of two-year colleges and for-profit schools say they prefer that most of their faculty be full timers on annual contracts (57% of two-year college presidents say so, as do 54% of for-profit college presidents).

Presidents who were faculty members before becoming administrators have greater preference for tenured, full-time faculty members (28%) than do presidents who were not professors in the past (14%).

In the Chronicle survey of four-year college presidents in 2005, a slight majority (53%) agreed with the general statement, “Tenure for faculty should be replaced by a system of long-term contracts.”

Presidents of Selective Colleges

Presidents of the nation’s most selective four-year colleges and universities are notably more upbeat about the state and future of U.S. education than are other presidents. Four-in-ten (40%) say the U.S. system is the world’s best, compared with 22% of presidents of moderately selective schools and 14% of the presidents of the least selective schools.

Presidents of the nation’s most selective four-year colleges and universities are notably more upbeat about the state and future of U.S. education than are other presidents. Four-in-ten (40%) say the U.S. system is the world’s best, compared with 22% of presidents of moderately selective schools and 14% of the presidents of the least selective schools.

Three-quarters (76%) say it will be the best or one of the best in the world in 10 years, compared with 62% of the presidents of moderately selective schools and 37% of the presidents of the least selective schools.

For this analysis, only four-year institutions were included. They were divided into three selectivity levels based on ratings provided by Barron’s Profile of American Colleges 2011 that include incoming students’ high school class rank, high school grade-point average and standardized test scores, as well as the college’s acceptance rate. The Pew Research survey sample included 196 presidents of the most selective schools, 351 presidents of moderately selective schools and 150 presidents of least selective schools, which included some not listed in the Barron’s guide.

On the question about the mission of higher education, the presidents of the most selective schools are more likely than others to endorse a broad education focused on intellectual growth—73% say it is the most important role of higher education in the lives of students. They are less likely than other presidents to say it is very important that colleges provide training for a specific career or profession (15% do) or focus on skills that will help students improve their potential earnings (32%).

As for cost, slightly more than half of the presidents of the most selective schools (52%) say college is affordable for most people, a contrast to the majority of other college presidents who say college is not affordable.

These presidents of the most selective institutions are more likely than others to say that the bulk of educational expenses at their institutions are paid by students and their families (42%). But 43% say scholarships and grants are their students’ main source of funding, higher than the share of least-selective presidents who say the same (21%).

Presidents of highly selective institutions are more likely than other presidents to say students and their families get more value now for the money they spend than was the case a decade ago—36% say so. They do not differ significantly from moderately selective college presidents on the question of whether higher education currently offers excellent or good value for the money spent; both groups rate current value more highly than do presidents of the least selective institutions.

As far as judging students, the most selective college presidents disagree with others about student workload. While half of moderately selective presidents (50%) and 53% of the least selective college presidents say students are studying less than they used to, only 38% of the most selective college presidents say so.

In terms of admissions criteria for students, the presidents of the most selective institutions are more likely than other presidents to say race or ethnicity should be a major factor once academic qualifications have been accounted for (19%, with an additional 54% saying it should be a minor factor). They also are more likely to say that socioeconomic status (46%), the legacy factor of family ties to the institution (59%) and where the student is from (56%) should be a minor factor in admissions.

Not surprisingly, the presidents of the most selective institutions place more emphasis than do others on academics as an attraction to students (96% say the strength of their academic programs is very important in this regard). They also place more emphasis than other presidents on the quality of student life; 74% say it is very important in attracting students.

As for how the public should assess higher education, the presidents of selective institutions are more likely than others to say that the selectivity of a school is a somewhat or very effective means (64%). They are more likely to say standardized test scores are somewhat to very effective (70%). They also are less fond of accreditation as a metric: 34% say it is not too effective or not at all effective.

The topic of tenure also divides presidents of the most selective schools from other presidents. Among heads of the most selective schools, 58% say they would prefer that most faculty members be full-time tenured teachers. That compares with 33% of moderately selective college presidents and 11% of least selective college presidents.

Optimists and Pessimists on Direction of Higher Education

Because a notable share of college presidents say the U.S. higher education system is heading in the wrong direction, this section analyzes the differences on other questions among presidents who are negative about the direction of higher education today (“pessimists” for short) and those who have positive views about the direction of higher education (“optimists”). Overall, 38% of college presidents say the higher education system is headed in the wrong direction, while 60% say it is headed in the right direction. Heads of for profit-institutions (65%) are especially likely to be pessimists, but so are a notable share of presidents of four-year private colleges (35%), four-year public institutions (33%) and two-year colleges (30%).

Generally, pessimists on this question also have downbeat views on other broad questions on the state of higher education today, its value and the quality of students.

Pessimists are more likely than optimists to say the U.S. system is average or below average now compared with others worldwide (20% to 6%). They also are more likely than optimists to predict it will be average or below average in a decade (33% to 8%).

A lower share of pessimists than optimists say higher education today provides good value for the money spent on it (61% to 86%) by students and their families. A higher share of pessimists than optimists say it provides less value than a decade ago (48% to 26%). As far as providing academic programs to meet the needs of today’s economy, pessimists are more likely than optimists to say higher education does only a fair to poor job (43% to 11%). They are more likely than optimists to say higher education does a worse job at providing academic programs for today’s economy than a decade ago (24% to 9%).

A lower share of pessimists than optimists say higher education today provides good value for the money spent on it (61% to 86%) by students and their families. A higher share of pessimists than optimists say it provides less value than a decade ago (48% to 26%). As far as providing academic programs to meet the needs of today’s economy, pessimists are more likely than optimists to say higher education does only a fair to poor job (43% to 11%). They are more likely than optimists to say higher education does a worse job at providing academic programs for today’s economy than a decade ago (24% to 9%).

Pessimists also are more critical of today’s students than are the optimists. Among pessimists, 66% say public high schools are doing a worse job than in the past of preparing students for college; 52% of optimists say so. Well over half–58%–say students are studying less than they used to, compared with 47% of optimists who say so.

The two groups also have somewhat different views about the role of higher education in students’ lives. Pessimists are less likely than optimists (38% to 48%) to believe the most important purpose of higher education is to provide a broad-based education that promotes intellectual growth. They are somewhat more likely than the optimists to think higher education’s most important role for students should be specific skills training or assistance in improving earnings potential.

Responses to this question are influenced by a disproportionate share of heads of for-profit institutions who are among the pessimists. For-profit presidents make up 18% of the weighted survey sample, but they account for 30% of pessimists.

There are no significant differences between pessimists and optimists on a number of survey questions, including the broad role of colleges in society and the affordability of a college education for most people.

Mission of Higher Education

What are the differences in views between college presidents who believe higher education’s most important role is in promoting intellectual or personal growth, and those who favor a role more oriented toward preparation for the world of work or specific jobs?

As noted earlier, presidents are nearly evenly split on whether intellectual growth or preparation for the world of work is the primary role. Presidents of for-profit schools are more likely to tilt toward preparation for the world of work; they account for a third (32%) of presidents who say so, even though for-profit institutions account for only 18% of the weighted survey sample.

Presidents who endorse the mission of promoting intellectual growth are more likely to say higher education in the United States is headed in the right direction (65% to 55%). They are more likely to say the U.S. system will be the best or one of the best in the world (63% to 44%). And they are more likely to say that U.S. higher education provides excellent or good value for the money students and their families spend on it (85% to 68%).

Those presidents who favor workplace preparation are gloomier about the quality of today’s students: 57% say they are studying less than students did a decade ago, compared with 46% of presidents who favor the mission of promoting intellectual growth.

The Value of College

The Value of College