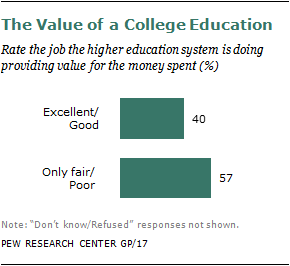

Amid rising costs and a sluggish economy, many Americans are questioning whether a college education is good value for the money. A large majority (75%) of the public says college is no longer affordable for most Americans. And only four-in-ten say the higher education system does an excellent (5%) or good (35%) job providing value to students given the amount of money they and their families are paying for college.

While the share of adults enrolled in college has increased to record levels in recent decades, a sizable minority of young adults are still not going to college. Most point to financial barriers when asked why they are not continuing their education.

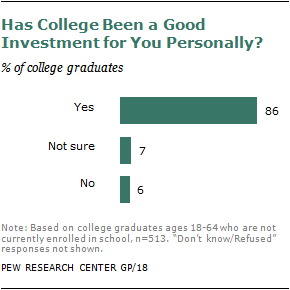

In spite of these and other misgivings among the public about higher education, nearly all college graduates (86%) say that college has been a good investment for them personally. And their incomes reflect this. Over the course of their work life, college graduates on average earn nearly $650,000 more than high school graduates, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of census data.4

As college costs have risen in recent decades, so, too, has the share of students taking out loans to finance their education. The amount each student borrows keeps growing as well: the average borrower graduating from a four-year college today leaves school with roughly $23,000 of student debt. And as the federal government and most state governments reduce spending on higher education to help close huge budget deficits, the need for students to borrow is likely to grow over time. This will not sit well with the public; according to the survey, less than half (48%) believes that students and their families should bear the main burden of paying for a college education.

The survey also finds that the public sees higher education as having two basic missions of similar importance. Some four-in-ten say the main purpose of college should be to help an individual grow personally and intellectually, while nearly half say it should be to teach specific skills and knowledge that can be used in the workplace.

The Costs and Benefits of Higher Education

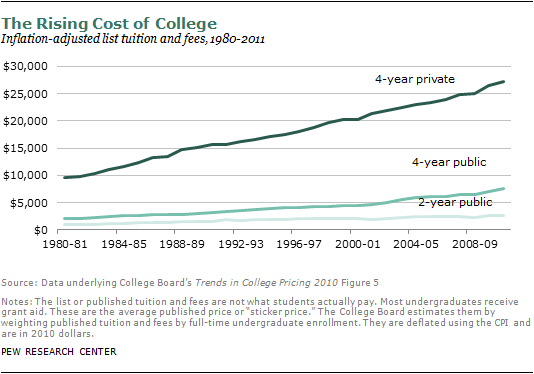

College costs have been on the rise for the past several decades, far outpacing the rate of inflation. The increases have been particularly sharp since 2000, especially among public four-year institutions. The average cost of tuition and fees at a four-year public college or university rose from $2,119 in 1980-81 to $7,605 in 2010-11 (all figures adjusted for inflation to 2010 dollars), an increase of 259%. At four-year private colleges, the average inflation-adjusted rise went from $9,535 in 1980-81 to $27,293 in 2010-11—an increase of 186%. Even the cost of two-year public colleges rose substantially over this period. In the 1980-81 school year, the average cost of tuition and fees at a two-year community college was $1,031. By 2010-11, that had increased 163% to $2,713.

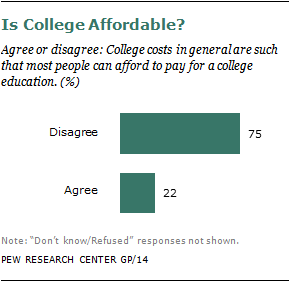

Not only has a college education become more expensive, but in the eyes of most Americans, it is now out of reach. Only one-in-five adults (22%) agree that college costs in general are such that most people are able to afford to pay for a college education. Fully three-quarters of adults disagree with this statement.

Not only has a college education become more expensive, but in the eyes of most Americans, it is now out of reach. Only one-in-five adults (22%) agree that college costs in general are such that most people are able to afford to pay for a college education. Fully three-quarters of adults disagree with this statement.

Concern about the cost of college, while widespread throughout the population, is felt more acutely by some groups than others. Adults ages 50 and older are more likely than those under age 50 to question the affordability of college. Among those ages 50 and older, more than eight-in-ten disagree with the notion that most people are able to afford to pay for college. This compares with roughly seven-in-ten among those under age 50. Men ages 50 and older (many of whom may be in the midst of paying for their children’s college education) are especially concerned about college costs: 83% doubt that most people can afford to pay for college.

Adults who graduated from college and those who did not are equally skeptical about the affordability of college. And among college graduates, those who attended public institutions are just as likely as those who attended private schools to reject the idea that college is affordable for most people.

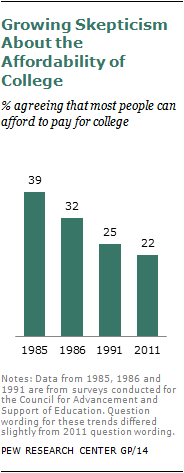

Public concern over the cost of college is not a new phenomenon. Surveys conducted in the mid-1980s and early 1990s for the Council for Advancement and Support of Education found solid majorities of the public questioning the affordability of college. Nonetheless, the percentage agreeing that “most people can afford to pay for a college education” has fallen significantly over time. In 1985, 39% of adults agreed that most people can afford a college education. By 1991, that share had fallen to 25%.

Public concern over the cost of college is not a new phenomenon. Surveys conducted in the mid-1980s and early 1990s for the Council for Advancement and Support of Education found solid majorities of the public questioning the affordability of college. Nonetheless, the percentage agreeing that “most people can afford to pay for a college education” has fallen significantly over time. In 1985, 39% of adults agreed that most people can afford a college education. By 1991, that share had fallen to 25%.

In spite of rising concerns over the cost of higher education, the public places a great deal of importance on a college degree. In a 2009 Pew Research Center survey, 74% agreed that in order to get ahead in life these days, it’s necessary to get a college education.

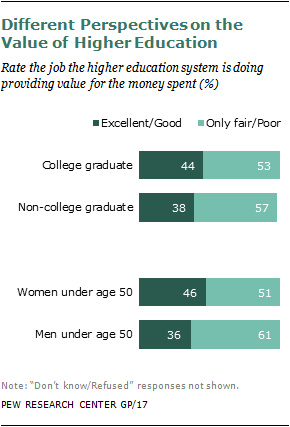

Even so, the higher education system as a whole gets relatively low ratings from the public for the job it is doing providing value for the money spent by students and their families. When asked to rate the higher education system in this regard, only 5% of adults say it is doing an excellent job providing value for the money students and their families are spending. An additional 35% say the higher education system is doing a good job. A majority gives the higher education system only a fair (42%) or a poor (15%) rating.

There isn’t much difference in views on this question between college graduates and those without a college degree. Among all college graduates, 44% say the higher education system is doing an excellent or good job providing value. A narrow majority (53%) gives the higher education system a rating of only fair or poor. Among those who do not have a college degree, 38% say the higher education system is doing an excellent or good job, while 57% say it is doing only a fair or poor job. These marginal differences are not statistically significant.

There isn’t much difference in views on this question between college graduates and those without a college degree. Among all college graduates, 44% say the higher education system is doing an excellent or good job providing value. A narrow majority (53%) gives the higher education system a rating of only fair or poor. Among those who do not have a college degree, 38% say the higher education system is doing an excellent or good job, while 57% say it is doing only a fair or poor job. These marginal differences are not statistically significant.

Opinion on this matter is consistent across racial and ethnic groups as well. Majorities of whites, blacks and Hispanics say the higher education system is doing only a fair or poor job in terms of providing value for the money spent by students and their families.

Women, who have made substantial gains in educational attainment in recent decades, have a more favorable view of the higher education system overall than do men. This gender gap is based solely on differences between men and women under the age of 50. Among women in that age cohort, nearly half (46%) say the higher education system is doing an excellent or good job providing value for the money spent. This compares with only 36% of men under age 50. More than six-in-ten men in this age group (61%) rate the higher education system only fair or poor in this regard.

Women, who have made substantial gains in educational attainment in recent decades, have a more favorable view of the higher education system overall than do men. This gender gap is based solely on differences between men and women under the age of 50. Among women in that age cohort, nearly half (46%) say the higher education system is doing an excellent or good job providing value for the money spent. This compares with only 36% of men under age 50. More than six-in-ten men in this age group (61%) rate the higher education system only fair or poor in this regard.

Personal Evaluations

These negative assessments of the job the higher education system is doing generally do not appear to be tied to one’s personal experience with college. While more than half of college graduates say the higher education system is not doing a good job providing value for the money students and their families are spending, most of those same graduates say their investment in a college education was worth it.

These negative assessments of the job the higher education system is doing generally do not appear to be tied to one’s personal experience with college. While more than half of college graduates say the higher education system is not doing a good job providing value for the money students and their families are spending, most of those same graduates say their investment in a college education was worth it.

When asked whether college has been a good investment for them personally, considering how much they or their family paid for it, fully 86% of college graduates say it has been a good investment. Only 6% say college has not been a good investment for them, and 7% say they are not sure.

When asked whether college has been a good investment for them personally, considering how much they or their family paid for it, fully 86% of college graduates say it has been a good investment. Only 6% say college has not been a good investment for them, and 7% say they are not sure.

Likewise, those who are currently enrolled in college express a strong belief that they are making a worthwhile investment. Among current college students, 84% think college will be a good investment, considering what they or their families are paying for it. Some 14% say they are not sure if it will be a good investment, and only 2% think it will not be a good investment.

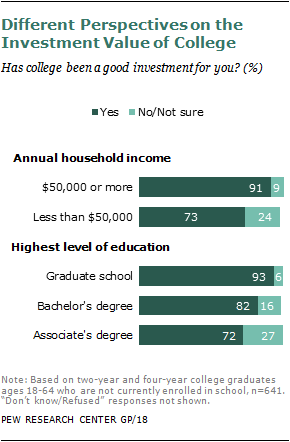

Among college graduates, men and women are equally likely to say college has been a good investment for them. Recent college graduates (those under age 30) are nearly as likely as those over age 30 to say college has been a good investment. One key factor that correlates with attitudes about the investment value of a college education is annual household income. College graduates with an annual income of less than $50,000 are less likely than those making $50,000 or more to say college has been a good investment (73% vs. 91%).

In addition, college graduates who went on to pursue graduate or professional school are among the most likely to say their investment in college has paid off. More than nine-in-ten adults with some graduate experience (93%) say college was a good investment for them. This compares with 82% of those with a bachelor’s degree who did not go on to graduate school and 72% of those with an associate degree.

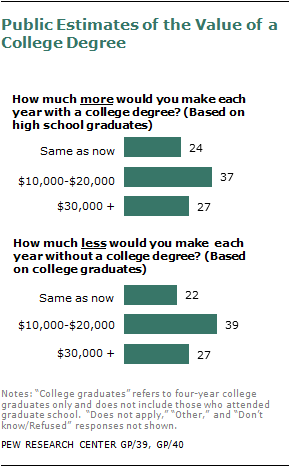

The public is correct in its assessment that a college education is a good investment, at least in economic terms. Research has shown that college graduates have much greater earning potential than do those without a college degree and that, in fact, over the course of a work life, the gap in overall earnings between the typical college graduate and the typical high school graduate is estimated to be $650,000.5

The public is correct in its assessment that a college education is a good investment, at least in economic terms. Research has shown that college graduates have much greater earning potential than do those without a college degree and that, in fact, over the course of a work life, the gap in overall earnings between the typical college graduate and the typical high school graduate is estimated to be $650,000.5

The public’s collective judgment about the worth of a college degree is quite accurate. Survey respondents who have no formal education beyond high school were asked to estimate how much more they would earn each year if they had a college degree. While one-in-four (24%) say they would earn about the same amount as now, a large majority say they would be making considerably more money. More than one-third (37%) say they would be making between $10,000 and $20,000 more a year, and 27% say their incomes would be at least $30,000 higher each year. Overall, the median of all responses is $20,000.

In the same survey, respondents who have a four-year college degree and did not go on to graduate school were asked how much less money they thought they would make a year if they did not have their degree. The median response among this group was also $20,000. Four-in-ten (39%) say they would be making between $10,000 and $20,000 less each year without their degree, and 27% estimate their annual income would be at least $30,000 less each year.

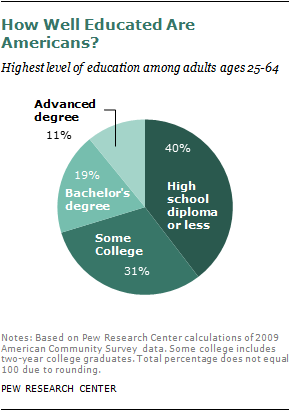

How many Americans are able to take advantage of these benefits? According to 2009 data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, less than a third (30%) of adults ages 25 to 64 have a four-year college degree. Among that same age group, 19% have a bachelor’s degree only while 11% have an advanced degree. A similar share (31%) attended college but do not have a four-year degree. This includes 8% who have an associate degree. Four-in-ten have a high school diploma or less.

How many Americans are able to take advantage of these benefits? According to 2009 data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, less than a third (30%) of adults ages 25 to 64 have a four-year college degree. Among that same age group, 19% have a bachelor’s degree only while 11% have an advanced degree. A similar share (31%) attended college but do not have a four-year degree. This includes 8% who have an associate degree. Four-in-ten have a high school diploma or less.

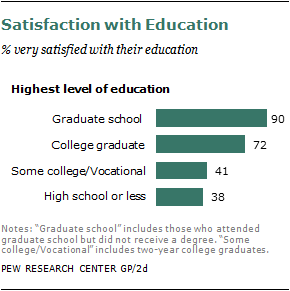

The Pew Research survey asked respondents from all educational backgrounds how satisfied they are overall with their education. Half of all adults ages 18 and older say they are very satisfied with their education. An additional 32% are somewhat satisfied, 10% are somewhat dissatisfied and 5% are very dissatisfied.

Whites (53%) are more satisfied with their education than are blacks (42%) or Hispanics (42%). Hispanic women are among the least satisfied (15% are very dissatisfied). But overall, men and women are equally satisfied with their education.

Satisfaction with education is strongly correlated with level of academic attainment. Adults who have an undergraduate degree and have gone on to graduate school are the most highly satisfied with their education—90% say they are very satisfied. Among those with a four-year college degree who did not go on to graduate school, 72% are very satisfied. Satisfaction drops off sharply from there. Among those who attended college but did not receive a bachelor’s degree, 41% are very satisfied, and among those who have no formal education beyond high school, 38% are very satisfied.

Satisfaction with education is strongly correlated with level of academic attainment. Adults who have an undergraduate degree and have gone on to graduate school are the most highly satisfied with their education—90% say they are very satisfied. Among those with a four-year college degree who did not go on to graduate school, 72% are very satisfied. Satisfaction drops off sharply from there. Among those who attended college but did not receive a bachelor’s degree, 41% are very satisfied, and among those who have no formal education beyond high school, 38% are very satisfied.

Why Not Go to College?

While college enrollment rates have risen steadily in recent decades, there remains a sizable share of young people who do not graduate from college. Among survey respondents ages 18-34, 48% did not have a bachelor’s degree and were not currently enrolled in school.

While college enrollment rates have risen steadily in recent decades, there remains a sizable share of young people who do not graduate from college. Among survey respondents ages 18-34, 48% did not have a bachelor’s degree and were not currently enrolled in school.

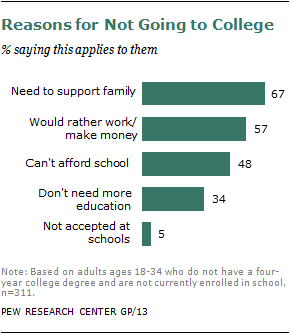

These respondents were asked why they have not continued their education. For most of them, the reasons are economic. Two-thirds (67%) say they have not continued their education because they need to support their family. Nearly six-in-ten (57%) say they would rather work and make money than go to school. And 48% say they cannot afford to continue with school.

Relatively few (34%) say they do not need more education to pursue their chosen career. And only 5% say the reason they have not continued their education is that they were not accepted to the schools they wanted to attend.

These young people who are not on the college track are disproportionately Hispanic. Among Hispanics ages 18-34, roughly two-thirds (65%) do not have a college degree and are not currently in school. This compares with 47% of blacks and 45% of whites in the same age group. Those not on the college track are also more likely to come from low-income households. Among those younger than 35 with annual household incomes of less than $30,000, 59% do not have a college degree and are not currently enrolled. This compares with only 35% of those who come from households with incomes of $50,000 or higher.

Although they didn’t graduate from college, these young people are nearly as likely as those who do have a degree to say a college education is important in helping a young person succeed in the world today. Among those ages 18-34, 71% of those without a college degree and 82% of those with say a college education is extremely or very important in helping a young person succeed.

Paying for College

For the millions of young Americans and their parents facing the challenge of financing a college education, the question of who pays, and how much, is vital. Even though roughly two-thirds of currently enrolled college students receive some type of financial assistance, a growing share of college graduates are leaving school with a significant amount of debt.

For the millions of young Americans and their parents facing the challenge of financing a college education, the question of who pays, and how much, is vital. Even though roughly two-thirds of currently enrolled college students receive some type of financial assistance, a growing share of college graduates are leaving school with a significant amount of debt.

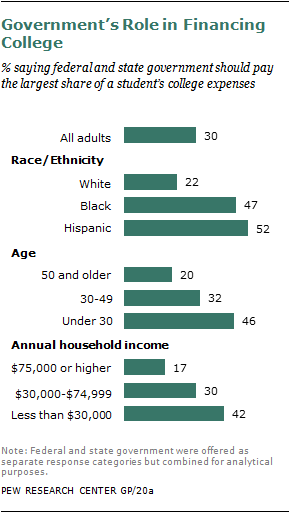

The public believes that college students and their families bear a large responsibility when it comes to paying for their education. However, they also see a significant role for state and federal governments as well as private sources of funding. When asked who should pay the largest share of a student’s overall college expenses, 48% of adults say it should be the students and their families. Three-in-ten say it should be either the federal (18%) or state (12%) government. Only 5% say private donors or endowments should cover most of the cost of college. The remainder either says it should be some combination of these sources (13%) or they do not know (4%).

At a time when the federal government and most state governments are under intense pressure to reduce spending in a variety of areas, the public is resistant to the idea of major cuts in educational support. In a survey conducted earlier this year by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, 62% of the public said they would like to see the federal government increase spending on education in the coming year. And when asked specifically about steps their state might take to balance its budget, only 31% of respondents favored decreasing funding for public colleges and universities. Fully two-thirds said their state should not decrease funding for higher education.6

There are significant differences across race, age and socioeconomic status on the question of who should pay for the bulk of a student’s college expenses. A majority of whites (57%) believe that students and their families should pay the largest share of a student’s college expenses. Only one-in-five whites (22%) say the federal or state government should pay the largest share. The balance of opinion is nearly reversed among blacks and Hispanics. Roughly half of blacks (47%) and Hispanics (52%) say federal and state government should pay the largest share of a student’s college expenses. Only three-in-ten say students and their families should be primarily responsible (31% of blacks and 27% of Hispanics).

There are significant differences across race, age and socioeconomic status on the question of who should pay for the bulk of a student’s college expenses. A majority of whites (57%) believe that students and their families should pay the largest share of a student’s college expenses. Only one-in-five whites (22%) say the federal or state government should pay the largest share. The balance of opinion is nearly reversed among blacks and Hispanics. Roughly half of blacks (47%) and Hispanics (52%) say federal and state government should pay the largest share of a student’s college expenses. Only three-in-ten say students and their families should be primarily responsible (31% of blacks and 27% of Hispanics).

Younger adults are much more likely than their older counterparts to say government should play a central role in financing students’ educations. Among those under age 30, 46% say federal or state government should pay the largest share of a student’s college expenses. This compares with 32% of those ages 30-49 and only 20% of those ages 50 and older.

And not surprisingly, income is also linked to views about who should pay for college. More than four-in-ten of those with annual household incomes less than $30,000 say government should pay the biggest share of a student’s college education. Among those with annual incomes in excess of $75,000, only 17% share this view.

Among those who have gone to college, most say either they themselves (28%) or their parents (27%) paid for most of their educational expenses. Roughly one-in-five (22%) say they received scholarship money or financial aid that covered most of the costs, and 17% say they relied mainly on student loans that they had to pay back later.7

Among those who have gone to college, most say either they themselves (28%) or their parents (27%) paid for most of their educational expenses. Roughly one-in-five (22%) say they received scholarship money or financial aid that covered most of the costs, and 17% say they relied mainly on student loans that they had to pay back later.7

College graduates are much more likely than those who attended school beyond high school but did not earn a four-year degree to report that their parents paid most of their college expenses. Among four-year college graduates, 35% say their parents paid. This compares with only 17% among those who did not graduate from a four-year college. Fully a third of those who did not graduate from college say they paid most of their educational expenses themselves, compared with 24% of college graduates.

Student Loans and the Burden of Debt

While 17% of adults with some postsecondary experience say they relied mainly on student loans to finance their education, a much larger share of students take out loans to pay for some portion of their college education.

While 17% of adults with some postsecondary experience say they relied mainly on student loans to finance their education, a much larger share of students take out loans to pay for some portion of their college education.

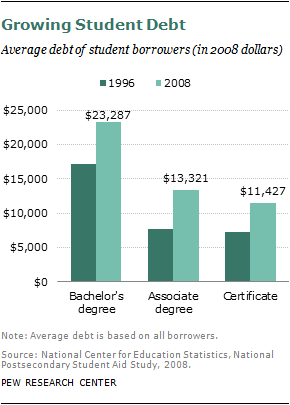

As college costs have risen, the share of students borrowing money to pay for college has increased substantially. According to a Pew Research analysis of data from the National Center for Education Statistics, the share of degree recipients who took out loans to finance their education increased from 52% in 1996 to 60% in 2008.8 This represents the share who borrowed for all types of schools, ranging from for-profit certificate programs to not-for-profit, four-year baccalaureate programs.

The rate of borrowing is significantly higher among students who received degrees or certificates from for-profit schools. Nearly all of those students (95%) took out loans to pay for their education. This compares with 72% of students who received their degree from a private, not-for-profit school and 50% who borrowed to attend a public college or university. Overall, students who earned a bachelor’s degree in 2008 were much more likely than those earning an associate degree to have borrowed money (66% vs. 48%).

Not only has the share of students borrowing for college increased, but the average amount of

money those students are borrowing has also risen substantially. The average student borrower who earned a bachelor’s degree in 2008 left school owing more than $23,000. This is up from roughly $17,000 in 1996. Among borrowers who earned an associate degree in 2008, the average level of debt exceeded $13,000 (nearly double the average in 1996).

While the burden of student debt is substantial, its impact does not seem to be crushing. A majority (63%) of survey respondents who reported having taken out loans to finance their postsecondary education say they have paid back all of those loans. Roughly 35% say they are still paying their loans back or have deferred payment.

While the burden of student debt is substantial, its impact does not seem to be crushing. A majority (63%) of survey respondents who reported having taken out loans to finance their postsecondary education say they have paid back all of those loans. Roughly 35% say they are still paying their loans back or have deferred payment.

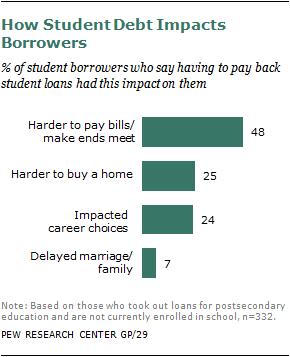

All of the borrowers were asked what kind of impact having to pay back their student loans has had on them personally. Roughly half (48%) say having to pay back their student loans made it harder for them to pay other bills and make ends meet. Beyond that, relatively few borrowers report major upheaval in their life as a result of having to pay back student loans. One-in-four say paying back their student loans has made it harder for them to buy a house. Roughly the same proportion (24%) says it has had an impact on the kind of career they are pursuing. And 7% say having to pay back student loans has delayed their getting married or starting a family.

Kids, College and Saving

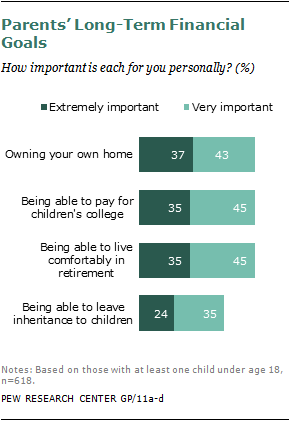

Given the rising cost of college, saving for a child’s education has become a daunting task for many parents. Being able to pay for a child’s education is an important long-term financial goal for most parents of school-aged children. Among all parents with at least one child under age 18, eight-in-ten say this is an extremely important (35%) or very important (45%) goal.

Given the rising cost of college, saving for a child’s education has become a daunting task for many parents. Being able to pay for a child’s education is an important long-term financial goal for most parents of school-aged children. Among all parents with at least one child under age 18, eight-in-ten say this is an extremely important (35%) or very important (45%) goal.

In the eyes of parents, being able to pay for their children’s college education is just as important as being able to own a home or live comfortably in retirement. And it’s more important than being able to leave an inheritance to their children.

Mothers and fathers place roughly the same degree of importance on being able to pay for their children’s college education. Black parents (55%) are more likely than white (31%) or Hispanic (35%) parents to say this is extremely important.

A parent’s own educational background does not have a significant impact on the importance they place on being able to provide for their children’s educational needs. Parents who never attended college are just as likely as those who earned a four-year college degree to say being able to pay for their children’s college education is extremely important.

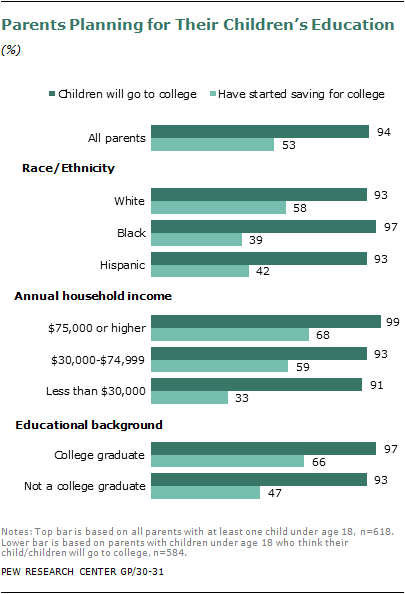

The vast majority of parents expect that their children will pursue a college education. Among those with one or more children under age 18, 94% expect at least one of their children will go to college. There are no significant differences across racial or ethnic groups—white, black and Hispanic parents are equally likely to think their children will go to college. In addition, there is very little variance across income groups. While 99% of parents with annual household incomes of $75,000 or higher think their children will go to college, 93% of those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 say the same, as do 91% of those making less than $30,000 a year. Again, parents’ own educational experience does not seem to influence the aspirations they have for their children. Parents who did not graduate from college (93%) are just as likely as college graduates (97%) to say their children will go to college.

Of those parents who think their children will go to college, roughly half (53%) say they have started saving. Here there are some significant differences across racial, ethnic and socioeconomic groups. White parents (58%) who think their children will go to college are more likely than black (39%) or Hispanic (42%) parents to say they have saved or invested money for those educational expenses.

Of those parents who think their children will go to college, roughly half (53%) say they have started saving. Here there are some significant differences across racial, ethnic and socioeconomic groups. White parents (58%) who think their children will go to college are more likely than black (39%) or Hispanic (42%) parents to say they have saved or invested money for those educational expenses.

The higher the parents’ household income, the more likely they are to have started saving for their children’s college education. Among parents who think their children will go to college, nearly seven-in-ten (68%) of those with incomes of $75,000 or higher say they have already started saving. This compares with only a third of parents with annual incomes of less than $30,000. In addition, two-thirds of parents who graduated from college (66%) say they have saved or invested money for their children’s college education, compared with fewer than half (47%) of parents who do not have a college degree.

Among those parents who have started saving for their children’s college education, a small majority feel pretty good about the progress they have made. Some 11% say they are ahead of where they think they should be at this point, and 42% say they are just about where they should be. At the same time, however, 46% say they are behind where they should be in terms of the progress they have made in saving for their children’s college expenses.

The Mission of Higher Education

Amid the rising cost of college and the changing demands of the economy, what is the mission of higher education today? Is it to promote personal and intellectual growth or is it to prepare an individual for a career? The public is divided over this question but leans a bit more heavily toward seeing college as a training ground for work. When asked what the main purpose of college should be, 47% say it should be to acquire specific skills and knowledge that can be used in the workplace, 39% of adults say it should be to help an individual grow personally and intellectually.

Amid the rising cost of college and the changing demands of the economy, what is the mission of higher education today? Is it to promote personal and intellectual growth or is it to prepare an individual for a career? The public is divided over this question but leans a bit more heavily toward seeing college as a training ground for work. When asked what the main purpose of college should be, 47% say it should be to acquire specific skills and knowledge that can be used in the workplace, 39% of adults say it should be to help an individual grow personally and intellectually.

A person’s educational background is strongly linked to views about the mission of higher education. Individuals who have pursued graduate studies beyond college are among the most likely to say the purpose of college should be to help an individual grow personally and intellectually. They choose this option over teaching skills and knowledge that can be used in the workplace by a more than two-to-one margin (56% vs. 26%). College graduates who have not gone to graduate school also choose personal and intellectual growth over specific skills and knowledge, although they are more evenly divided. Half say that individual growth is more important, and 40% say learning skills and knowledge that can be used in the workplace is what matters most.

Those who have not graduated from a four-year college have a different opinion about the main purpose of college. They are more likely than those who have a bachelor’s degree to say that college should prepare an individual for work. Among those who attended some college or had some vocational training beyond high school, 45% say the main purpose of college should be to teach specific skills and knowledge that can be used in the workplace. Four-in-ten (39%) say the purpose of college should be to help an individual grow personally and intellectually. Adults who have a high school diploma or less are even more likely to see college as a place to learn specific skills and knowledge. More than half (55%) say the mission of college should be to prepare in individual for work; only 31% say personal and intellectual growth should be the objective.

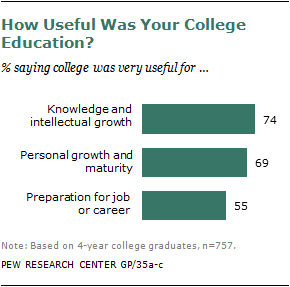

What has been the real-world experience of college graduates: Has college prepared them best for life or prepared them best for work? As it turns out, college graduates are more likely to say their college education helped them to grow intellectually and personally than they are to say it helped prepare them for a career. Among all college graduates, 74% say their college education was very useful in terms of increasing their knowledge and helping them to grow intellectually. More than two-thirds (69%) say college was very useful in helping them grow and mature as a person. Only 55% say college was very useful in preparing them for a job or career.

What has been the real-world experience of college graduates: Has college prepared them best for life or prepared them best for work? As it turns out, college graduates are more likely to say their college education helped them to grow intellectually and personally than they are to say it helped prepare them for a career. Among all college graduates, 74% say their college education was very useful in terms of increasing their knowledge and helping them to grow intellectually. More than two-thirds (69%) say college was very useful in helping them grow and mature as a person. Only 55% say college was very useful in preparing them for a job or career.

Graduates of two-year colleges are less likely than those who graduated from four-year colleges to point to the personal and intellectual benefits of college. Among those with an associate degree, 61% say college was very useful in increasing their knowledge and helping them to grow intellectually. Only 57% of two-year graduates say college helped them grow and mature (compared with 69% of four-year graduates). When it comes to preparing students for a job or career, four-year and two-year college graduates make similar assessments about the value of college. Just over half say it was very useful in this regard.

Succeeding in the World Today

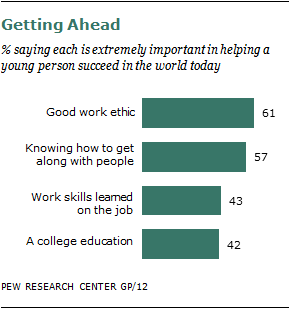

According to most adults, to succeed in the world today, a young person needs a college education. But that’s not all they need. In fact, in the public’s view, there are other things that are even more important. When asked how important a college education is in helping a young person succeed, 42% of adults say it is extremely important. An additional 35% say a college education is very important, and 22% say it is either somewhat important or not too important.

In the public’s view, however, certain character traits are even more important. Six-in-ten adults (61%) say a good work ethic is extremely important in helping a young person succeed in the world today. Nearly as many (57%) say knowing how to get along with people is extremely important. And some 43% say work skills learned on the job are extremely important—putting this on par with a college education in terms of its importance in helping young people succeed.

In the public’s view, however, certain character traits are even more important. Six-in-ten adults (61%) say a good work ethic is extremely important in helping a young person succeed in the world today. Nearly as many (57%) say knowing how to get along with people is extremely important. And some 43% say work skills learned on the job are extremely important—putting this on par with a college education in terms of its importance in helping young people succeed.

Interestingly, college graduates and those without a college degree do not differ dramatically on the question of what it takes to succeed in the world today. Four-year college graduates are somewhat more likely than those without a bachelor’s degree to say a good work ethic is extremely important in helping a young person succeed (68% vs. 58%). When it comes to having a college degree, college graduates are only slightly more likely than non-graduates to say this is extremely important (47% vs. 40%).

Women place more importance than men on having a good work ethic and knowing how to get along with people. However, men and women do not differ over the importance of having a college degree. Whites and blacks place more importance than Hispanics on having a good work ethic, knowing how to get along with people and work skills learned on the job. Blacks stand out in terms of the value they place on higher education. More than half (55%) say having a college degree is extremely important in helping a young person succeed in the world today. This compares with 41% of whites and 39% of Hispanics. This racial divide is driven mainly by the views of black women, 61% of whom say having a college education is extremely important.

Does More Education Mean More Satisfaction with Work?

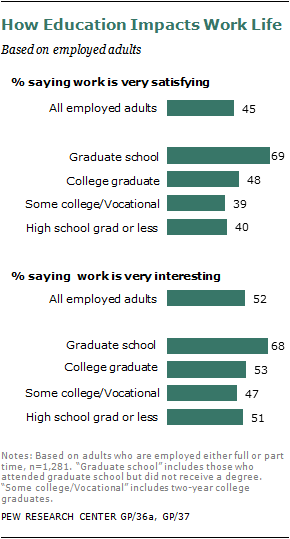

Most adults who have a job are satisfied with their work. However, higher education does seem to enhance a person’s work life—making it more satisfying, more interesting, and much more lucrative. Overall, 45% of employed adults say they are very satisfied with their current job or career. An additional 37% are somewhat satisfied, and 17% are dissatisfied (10% somewhat, 7% very). College graduates are significantly more satisfied with their work when compared with those who have not graduated from college. Among all graduates of a four-year college, 55% are very satisfied with their work. Only 40% of non-graduates say the same.

Most adults who have a job are satisfied with their work. However, higher education does seem to enhance a person’s work life—making it more satisfying, more interesting, and much more lucrative. Overall, 45% of employed adults say they are very satisfied with their current job or career. An additional 37% are somewhat satisfied, and 17% are dissatisfied (10% somewhat, 7% very). College graduates are significantly more satisfied with their work when compared with those who have not graduated from college. Among all graduates of a four-year college, 55% are very satisfied with their work. Only 40% of non-graduates say the same.

The happiest workers are those who pursued graduate studies beyond college. Among those with some graduate school experience, 69% are very satisfied with their current job. College graduates who did not go on to graduate school are only marginally more satisfied than those with less education. Men who attended graduate school are among the most satisfied with their work. Roughly three-quarters (74%) say they are very satisfied with their current job. This compares with 62% of women who went to graduate school.

Not only are they more satisfied with their work, but college graduates are also more likely than non-college graduates to report that their work is interesting. Again, it is the college graduates who pursued graduate studies who stand out in this regard. Nearly seven-in-ten (68%) of those with at least some graduate-level education say their work is very interesting. This compares with 53% of those with a four-year college degree who did not go on to graduate school and 49% of those without a four-year college degree.

Many American workers feel they are overqualified for their jobs. Overall, four-in-ten employed adults say they have more qualifications than their current job requires. Half say they have the right amount of qualifications, and 9% say they are under qualified. Among all college graduates, 33% say they are in a job that does not require a college degree. Those who have had some graduate training beyond college are less likely to find themselves in this situation—only 17% say they are working in a job that does not require a college degree. However, among four-year college graduates who did not go on to graduate school, 42% say their job does not require a college degree.

Not surprisingly, those who never attended college or fell short of attaining a degree are not likely to be in jobs that require a college degree. Among all those without a college education, a sizable minority say that not having a degree has held them back from pursuing certain employment opportunities. Three-in-ten say they have wanted to apply for a job but did not because they lacked a college degree; 13% say they have applied for a job and been turned down because they did not have a college degree.

Education and Economic Well-Being

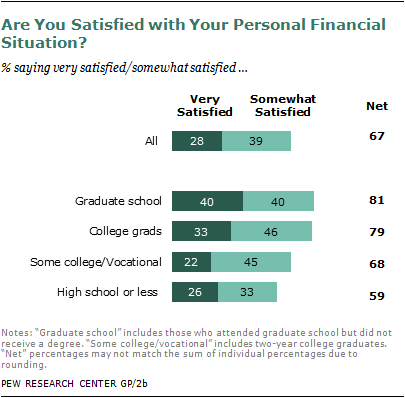

A majority of Americans (67%) are satisfied with their personal financial situation, though relatively few are very satisfied. Higher education is linked to greater financial satisfaction. Adults with college or postgraduate education are more likely to say they are “very satisfied” with their financial situation than are those with less education.

A majority of Americans (67%) are satisfied with their personal financial situation, though relatively few are very satisfied. Higher education is linked to greater financial satisfaction. Adults with college or postgraduate education are more likely to say they are “very satisfied” with their financial situation than are those with less education.

Financial satisfaction is also linked to employment status. Some 71% of employed adults say that they are satisfied with their financial situation, compared with 54% who are not employed. According to the survey, 73% of adults who have a four-year college degree are employed, versus 56% of adults who do not have a college degree.

Aside from the satisfaction differences due to employment status, employed adults with a higher education show a higher level of personal financial satisfaction than their less-educated counterparts. Among employed adults, 80% who have a college degree are satisfied with their personal financial situation, compared with 67% of adults who do not have a college degree.

When asked to compare their own standard of living to that of their parents at similar ages, 61% of Americans say that their standard of living is better and 23% say that it is about the same. This intergenerational upward mobility does not vary by a person’s educational attainment. Adults who attended graduate school are about as likely to say they are doing better than their parents (65%) as are those with some college education (62%) or even those with a high school education or less (58%).

When asked to compare their own standard of living to that of their parents at similar ages, 61% of Americans say that their standard of living is better and 23% say that it is about the same. This intergenerational upward mobility does not vary by a person’s educational attainment. Adults who attended graduate school are about as likely to say they are doing better than their parents (65%) as are those with some college education (62%) or even those with a high school education or less (58%).

Looking toward the next generation, nearly half of all adults (48%) think their children will surpass themselves in terms of standard of living, and two-in-ten (19%) think that their children will have the same standard of living as they have now.

Adults with the least education—those with a high school diploma or less—are the most optimistic. More than half of them (54%) think their children’s standard of living will be better than theirs, followed by half of those with some college education. In contrast, only 35% of adults with graduate school experience believe their children will do better than themselves, as do 42% of adults with a college degree who did not go on to graduate school.

At the same time, adults with a college or postgraduate education are more likely than those with less education to believe that their children’s standard of living will be similar to their own.

Adults with an associate degree are a somewhat of an anomaly. Compared with those who are less educated, these graduates of two-year colleges are less likely to say that their children’s living standards will surpass their own but more likely to say that their children will be worse off than they are. Specifically, 17% of associate degree holders expect that their children’s standard of living will be “much worse” than theirs, which is significantly higher than most adults, except for those with a high school education or less (11%).

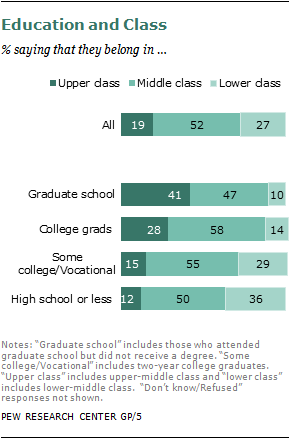

Survey respondents were asked to describe themselves in terms of the social classes, and slightly over half of the adults (52%) describe themselves as “middle class.” One-in-five (19%) identify themselves as upper class or upper-middle class, and the rest (27%) think of themselves as lower-middle or lower class.

Survey respondents were asked to describe themselves in terms of the social classes, and slightly over half of the adults (52%) describe themselves as “middle class.” One-in-five (19%) identify themselves as upper class or upper-middle class, and the rest (27%) think of themselves as lower-middle or lower class.

Education is closely related to how people see themselves on the socioeconomic ladder, especially at the top and bottom rungs. Relatively equal shares of the adults at each education level identify themselves as “middle class.” However, those who have attended graduate school are most likely to put themselves in the “upper class” category (41%), followed by college graduates who did not go on to graduate school (28%). Meanwhile, those who are without a college degree are more likely to identify themselves as “lower class” than the rest of adults.

Education, income and social class are closely related to each other. According to the survey, 56% of adults with a postgraduate education and 41% of adults with a college education have an annual family income of $75,000 or more, compared with only 23% of adults with some college education and 11% of adults with a high school education or less.

The Value of College

The Value of College