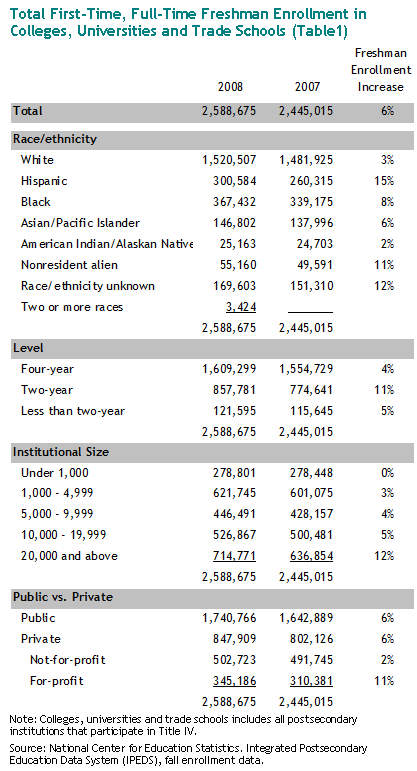

In fall 2008, a record 2.6 million first-time, full-time freshmen were enrolled in the nation’s postsecondary institutions. This was 144,000 more than the 2007 freshman class, a 6% increase, which was the largest since 1968 at the height of the Vietnam War.3

In fall 2008, a record 2.6 million first-time, full-time freshmen were enrolled in the nation’s postsecondary institutions. This was 144,000 more than the 2007 freshman class, a 6% increase, which was the largest since 1968 at the height of the Vietnam War.3

Booming freshman enrollments are the direct result of at least two factors. First, the nation’s high school graduating class in 2008 (3.3 million) is estimated to have been the largest ever (National Center for Education Statistics, 2010a). Second, and more importantly, record rates of young high school completers are immediately enrolling in college. In October 2008, 68.6% of high school completers were enrolled in college in the fall immediately after completing high school (matching the previous high). In October 2009, a record 70% of recent high school completers immediately entered college (a historical high for the data series, which began in 1959) (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010).

This growth in freshman enrollment coincided with greatly diminished labor market opportunities facing the nation’s youths. The official Bureau of Labor Statistics unemployment rate for teens ages 16 to 19 rose to 21% in December 2008 (from 17% at the recession’s onset in December 2007). The teen labor market deteriorated even more in 2009. By October 2009, teen unemployment reached its highest level (28%) in the history of the series dating back to 1948. By many labor market indicators, youths have been among the groups most severely affected by this recession (Hipple, 2010).

The strong growth in freshman enrollment suggests that youths do “adapt to circumstances.” That is, when faced with a decline in employer demand, they boost their school enrollment and continue living with their parents rather than striking out on their own (Card and Lemieux, 2000). Some detailed empirical studies indicate that U.S. college enrollments in modern times have behaved countercyclically (Dellas and Sakellaris, 2003; Betts and McFarland, 1995). Labor economists point out that a youth’s opportunity costs or forgone labor market earnings are one of the larger costs of pursuing college. During a recession, forgone earnings may be diminished and college effectively cheaper.

The strong growth in freshman enrollment suggests that youths do “adapt to circumstances.” That is, when faced with a decline in employer demand, they boost their school enrollment and continue living with their parents rather than striking out on their own (Card and Lemieux, 2000). Some detailed empirical studies indicate that U.S. college enrollments in modern times have behaved countercyclically (Dellas and Sakellaris, 2003; Betts and McFarland, 1995). Labor economists point out that a youth’s opportunity costs or forgone labor market earnings are one of the larger costs of pursuing college. During a recession, forgone earnings may be diminished and college effectively cheaper.

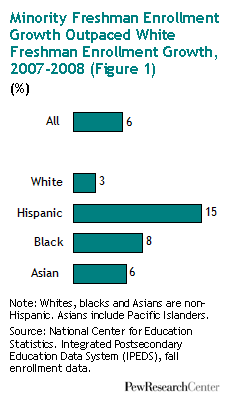

This report examines the most recent available college freshman enrollment data to look at the characteristics of these freshmen as well as the nature of the institutions that are educating them. In some ways, the freshman enrollment boom has been quite widespread and in other ways highly circumscribed. In terms of student characteristics, the enrollment boom seems to have been broad-based. For example, both male and female freshman enrollment increased 6%. The next section shows that much of the freshman growth was due to minority or nonwhite students. Reflecting the changing demographics of the nation’s high school graduating classes, around three-quarters of the freshman enrollment boom is due to minority freshman enrollment growth. Furthermore, the minority freshman growth was not confined to two-year colleges and less-than-two-year institutions. The minority growth was widespread in terms of the basic tiers of higher education.

The third and fourth sections of the report examine the impact of the growth on specific postsecondary institutions. It shows that the enrollment boom was concentrated in certain states and highly focused on a very small number of large colleges and universities. Of the 144,000 increase in freshman enrollment, about 72,000 occurred at just 109 colleges and universities, so less than 2% of the nation’s colleges and universities accommodated half of the enrollment boom.

The fifth section returns to focus on students and examines the impact of the recession on student employment. The last section examines whether large freshman classes have continued since 2008.