Social media has increased public access to information and created platforms for political activism. Yet some also say it is harmful to democracy.

This Pew Research Center analysis focuses on the perceived impact of social media on democracy in 27 countries in North America, Europe, the Middle East, the Asia-Pacific region, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America.

For non-U.S. data, this report draws on surveys of 20,944 respondents across 18 advanced economies conducted from Feb. 14 to June 3, 2022, and surveys of 10,235 respondents across eight emerging and developing economies (Argentina, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria and South Africa) conducted from Feb. 25 to May 22, 2023. The data was collected both face-to-face and over the phone. In Australia, we used a mixed-mode probability-based online panel.

In the United States, we surveyed 3,581 U.S. adults from March 21 to March 27, 2022. Everyone who took part in the U.S. survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

To compare educational groups across countries, we standardize education levels based on the UN’s International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED).

- In India, Indonesia, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Brazil, the lower education category is below secondary education, and the higher category is secondary or more.

- In Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, the UK, Australia, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Israel, Argentina and Mexico, the lower education category is secondary education or less, and the higher category is postsecondary or more.

- In the U.S., the lower education category is some college or less, and the higher category is a college degree or more.

Here is the question used for the analysis, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

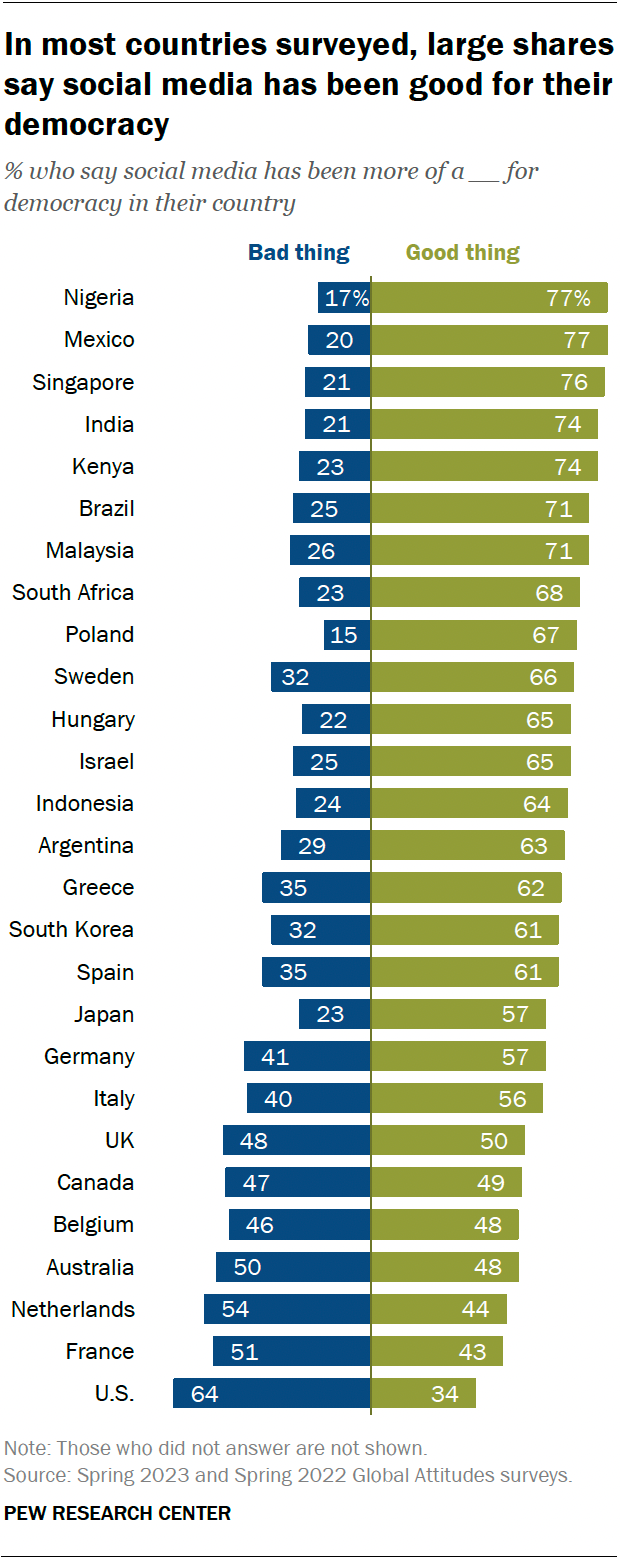

As social media use becomes more widespread globally, people in 27 countries surveyed by Pew Research Center between 2022 and 2023 generally see it as more of a good thing than a bad thing for democracy. In 20 of these countries, in fact, majorities say social media has benefited democracy in their nation.

People in emerging economies are particularly likely to say social media has advanced their democracy. Assessments are especially positive in Nigeria and Mexico, where nearly eight-in-ten (77% each) say social media has had a positive effect on democracy.

People are far less certain in other countries, including the Netherlands and France, where more say social media has had a negative effect on democracy than say it’s had positive effect. French President Emmanuel Macron has called for social media regulation to curb the spread of misinformation. In 2023, he also suggested that access to social media should be cut during times of social unrest, including during riots over police violence in France.

Meanwhile, Americans are the least likely to evaluate social media positively. Just 34% of U.S. adults say social media has been a good thing for democracy in the United States, while nearly twice as many (64%) say it has been a bad thing.

Related: Social Media Seen as Mostly Good for Democracy Across Many Nations, but U.S. is a Major Outlier

The role of social media in spreading misinformation has been widely discussed ahead of key U.S. elections. And though majorities in both parties say social media has been a bad thing for democracy in the U.S., Republicans and Republican-leaning independents are more likely to say this than Democrats and Democratic leaners (74% vs. 57%).

How do views on social media and democracy vary by age, education and other factors?

Age

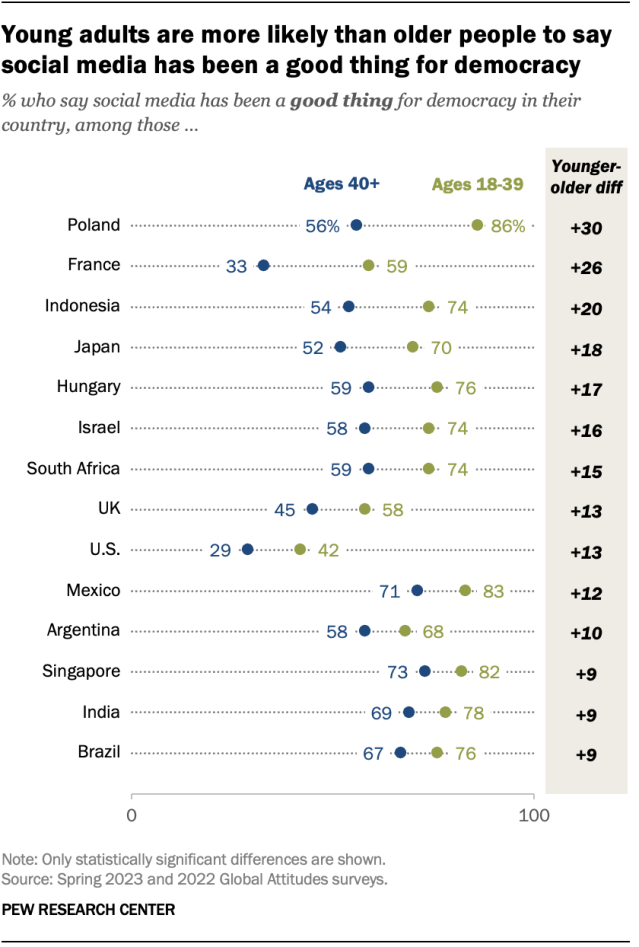

In 14 countries surveyed, younger adults are more likely than older people to say social media has been a good thing for democracy.

This difference is most prevalent in Poland, where 86% of adults under 40 say social media has benefited democracy in their country, compared with 56% of those ages 40 and older. Double-digit differences exist in 10 additional countries surveyed.

Education

In 13 countries, adults with more education are more likely than those with less schooling to say that social media has been a good thing for democracy. In South Africa, for example, there is a 22-percentage-point difference on this question between those with more education and those with less.

(Education systems differ by country, so in this analysis, levels of attainment for “more education” and “less education” also vary. Read the “How we did this” section for more information.)

Income

In some countries, adults with higher incomes are more likely than those with lower incomes to say social media is a good thing for democracy. In Belgium and the U.S., however, the reverse is true.

Social media use

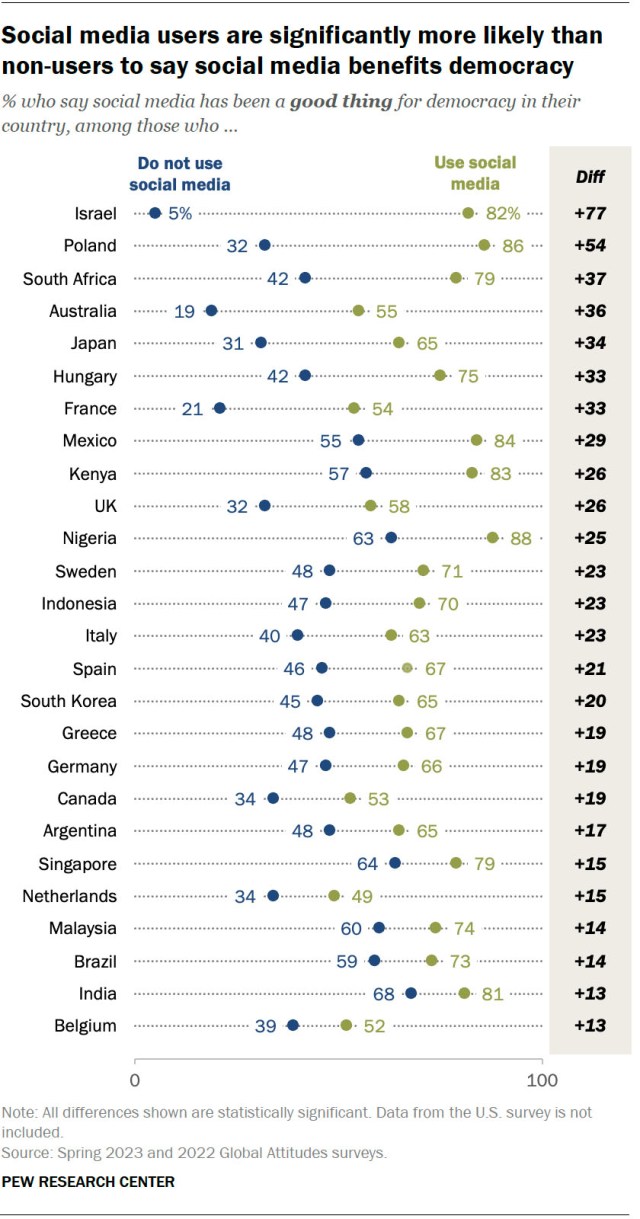

Those who use social media are significantly more likely than non-users to say that social media has benefited democracy in their country. In every country surveyed, there is a difference of at least 10 points between social media users and non-users on this question. Non-users, however, are also less likely to offer an opinion on this question in most places.

For example, in Israel, social media users are 77 percentage points more likely than non-users to say social media has been a good thing for democracy (82% vs. 5%). But about a quarter of non-social media users in Israel decline to provide a response, compared with just 5% of those who do use social media.

And in Poland, South Africa, Australia, Japan and elsewhere, social media users are far more likely than non-users to express a positive view of its effect on democracy. In every country surveyed, social media users are at least 10 points more likely to take this stance than non-users.

Note: Here is the question used for the analysis, along with responses, and the survey methodology.