One-in-five Asian American adults say they have hidden a part of their heritage – cultural customs, food, clothing or religious practices – from non-Asians at some point in their lives. Fear of ridicule and a desire to fit in are common reasons they give for doing this, according to a Pew Research Center survey of Asian adults in the United States conducted from July 2022 to January 2023.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to understand how many Asian American adults have hidden a part of their heritage and their reasons for doing so. Hiding one’s heritage can include food, culture, clothing or religious practices.

This analysis is based on a nationally representative survey of 7,006 Asian adults. The survey sampled U.S. adults who self-identify as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic ethnicity. It was offered in six languages: Chinese (Simplified and Traditional), English, Hindi, Korean, Tagalog and Vietnamese. Responses were collected from July 5, 2022, to Jan. 27, 2023, by Westat on behalf of Pew Research Center.

The survey included large enough samples of the Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese populations to report the findings for each group separately. These are the six largest origin groups among Asian Americans. These groups include those who identify with one Asian ethnicity only, either alone or in combination with a non-Asian race or ethnicity. For more details on how the survey was conducted, read the methodology. For the questions used in this analysis, read the topline questionnaire.

As part of the survey, respondents were asked if they have ever hidden a part of their heritage from people who are not Asian. Those who answered yes were asked in a follow-up open-ended question on why they do so. Pointwise mutual information was used to identify the 100 most distinctive terms that distinguish responses from U.S.-born and foreign-born respondents. The terms identified through this method represent the language that characterizes how respondents from either group answered the open-ended question.

The demographic analysis of Asian Americans is based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey from 2022 provided through Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) from the University of Minnesota. In this analysis, Asian Americans are defined as those who report their race as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic ethnicity.

The focus group analysis is based on 66 focus groups of Asian adults. The Center conducted these focus groups virtually from Aug. 4 to Oct. 14, 2021, with 264 total participants from 18 Asian origin groups. Quotations are not necessarily representative of the majority opinion in any particular group. Quotations may have been edited for grammar, spelling and clarity.

In this analysis, “immigrants” are people who were not U.S. citizens at birth but later came to the U.S. – in other words, those born outside the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories to parents who are not U.S. citizens.

“U.S. born” refers to people born in the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories, as well as those born elsewhere to parents who are U.S. citizens.

“Second generation” refers to people born in the 50 states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories with at least one immigrant parent.

“Third or higher generation” refers to people born in the 50 states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories, with each parent also born in one of those places.

Survey respondents’ primary language is based on their self-described speaking and reading abilities. People who are “origin language dominant” are more proficient in the Asian origin language of their family or ancestors than in English (i.e., they speak and read their Asian origin language “very well” or “pretty well” but rate their ability to speak and read English lower). “Bilingual” refers to those who are proficient in both English and their Asian origin language. People who are “English dominant” are more proficient in English than in their Asian origin language.

Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. The Center’s Asian American portfolio was funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts, with generous support from The Asian American Foundation; Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation; the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; the Henry Luce Foundation; the Doris Duke Foundation; The Wallace H. Coulter Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Long Family Foundation; Lu-Hebert Fund; Gee Family Foundation; Joseph Cotchett; the Julian Abdey and Sabrina Moyle Charitable Fund; and Nanci Nishimura.

We would also like to thank the Leaders Forum for its thoughtful leadership and valuable assistance in helping make this survey possible.

The strategic communications campaign used to promote the research was made possible with generous support from the Doris Duke Foundation.

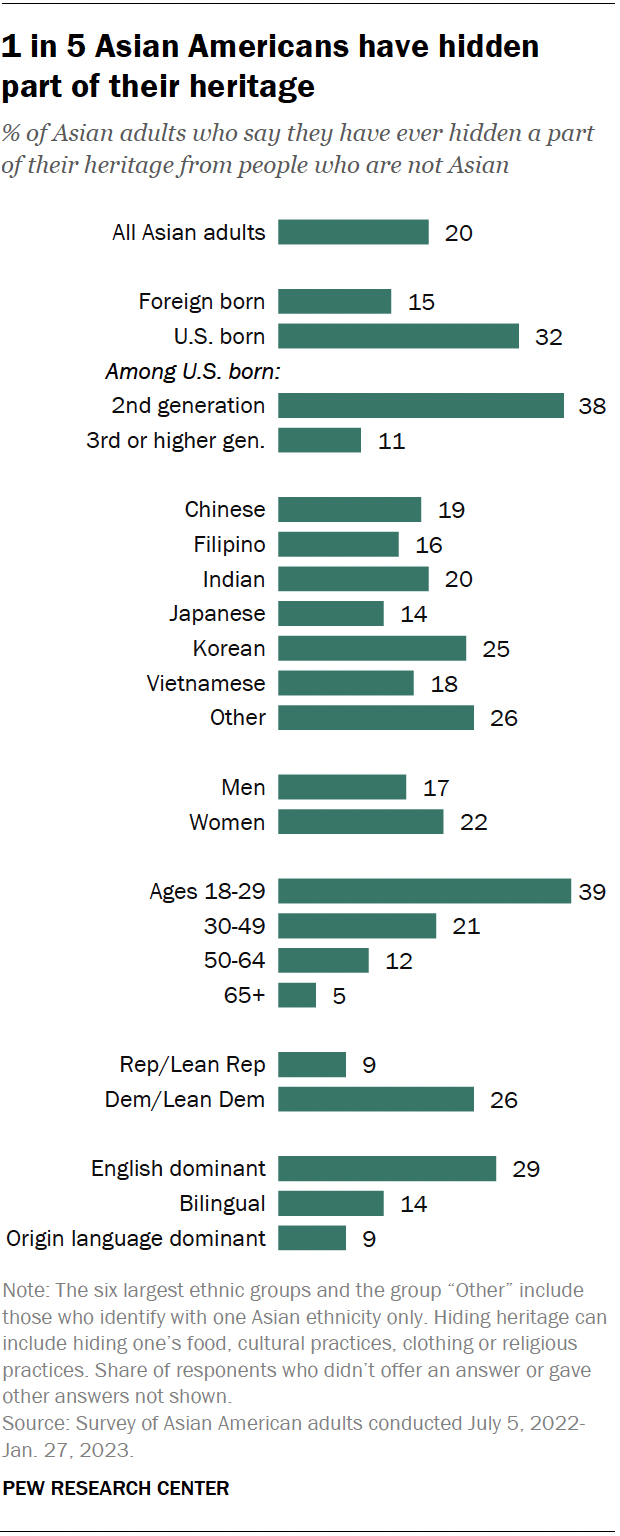

Birthplace and immigrant roots play a role in who is most likely to hide their heritage: 32% of U.S.-born Asian adults have done this, compared with 15% of immigrants. Among those born in the U.S., second-generation Asian adults (in other words, those with at least one immigrant parent) are more likely than third- or higher-generation Asian Americans (those with U.S.-born parents) to have hidden their culture from non-Asians (38% vs. 11%).

Second-generation Asian Americans make up 34% of the U.S. Asian population, at approximately 7.9 million people, according to a Center analysis of the 2022 Current Population Survey. The majority of this group (66%) is under age 30. And according to our survey, they also primarily speak English.

Aside from generational differences, here are other survey findings about who is most likely to have hidden their heritage from non-Asians:

- Korean Americans are more likely than some other Asian origin groups to say they have hidden part of their heritage. One-in-four Korean adults (25%) say they have done this, compared with smaller shares of Chinese (19%), Vietnamese (18%), Filipino (16%) and Japanese (14%) adults.

- Asian Americans ages 18 to 29 are about twice as likely as older Asian adults to have hidden their culture. About 39% of Asian adults under 30 have hidden their culture, food, religion or clothing from non-Asians. About one-in-five Asians ages 30 to 49 (21%) have done this, as have 12% of Asians 50 to 64 and 5% of those 65 and older.

- Asian adults who are Democrats or lean Democratic are much more likely than those who identify with or lean toward the Republican Party to have hidden their identity. Among Asian adults, 29% of Democrats have hidden their culture from others, compared with 9% of Republicans.

- Asian Americans who primarily speak English are more likely than those who primarily speak the language of their Asian origin country to have hidden part of their heritage. Some 29% of English-dominant Asian adults have hidden their heritage, versus 14% of those who are bilingual and 9% who primarily speak their Asian origin language.

Why some Asian Americans hide their heritage

Asian Americans who said they have hidden part of their heritage also shared why they did so. Some of the most common reasons were a feeling of embarrassment or a lack of understanding from others.

However, different immigrant generations also cited various other reasons for hiding their culture:

- Many recent Asian immigrants said they have tried to fit into the U.S. and fear that others may judge them negatively for sharing their heritage.

- U.S.-born Asian Americans with immigrant parents often said they hid their heritage when they were growing up to fit into a predominantly White society. Some in this generation mentioned wanting to avoid reinforcing stereotypes about Asians.

- Some multiracial Asian Americans and those with more distant immigrant roots (third generation or higher) said they had at times hidden their heritage to pass as White.

What U.S.-born Asian Americans say about growing up in the U.S.

In 2021, the Center conducted 17 focus groups in which Asian Americans born in the U.S. answered questions about their experiences growing up. Some second-generation Asian Americans shared distinct examples of hiding their heritage and having to balance their family’s cultural practices with the culture of broader American society:

“[It] was kind of that stigma when you were little, a teen, or you were younger that [you] don’t want to speak Chinese … because people would think that you’re a FOB [fresh off the boat] or an immigrant.” – Early 30s man with Chinese immigrant parents

“I remember in elementary school, I don’t even know what my mom brought me, [but] it was some Taiwanese dish. I guess it just had a more pungent smell to it. The kids would just be like, ‘Oh, what is that smell? You guys smell that?’ I would just cover my lid and be like, ‘Okay, I’m not going to eat my lunch.’” – Early 20s woman with Taiwanese immigrant parents

“[I] used to roll as Asian/Hispanic because I was too scared of my identity to say I was Pakistani. I remember 2011 or 2012, when [U.S. special operations forces] killed [al-Qaida leader Osama] bin Laden in Pakistan, after that happened, I was like, ‘Yeah, I’m definitely not saying I’m Pakistani,’ because people were coming up to me and they’re like, ‘Oh my God, they killed your uncle. They found him in your homeland.’” – Early 20s man with Pakistani immigrant parents

Alongside these struggles, many second-generation Asian Americans talked about being proud of their cultural background and wanting to share it with non-Asians:

“[W]hen I go to Cambodia and speak the language, it’s like connecting with an old friend … or meeting somebody from my past because so many of those ideas of what love is, of what it is to be part of a community, and even to live by example comes from having that language still alive within me.” –Early 30s man with Cambodian immigrant parents

“[T]here are going to be ups and downs. Definitely one of the downs is being labeled by other people for our differences. But one of our ups is that we have culture and language that we can always rely on; we have some diversity in customs and cultures that we could go back to. And if people are willing to experience these new differences, we can definitely pass it on and spread awareness of different cultures.” –Early 20s man with Korean immigrant parents