Just over a year ago, President Joe Biden signed a bipartisan bill that created a commission to study whether a National Museum of Asian Pacific American History and Culture should be established in Washington, D.C. As the commission begins its work, only about one-in-four Asian Americans (24%) consider themselves extremely or very informed about the history of Asian people in the United States, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis using data from a recent, nationally representative survey exploring the experiences, attitudes and views of Asians living in the U.S. The Center sampled 7,006 U.S. adults who self-identify as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic ethnicity. The survey was offered in six languages: Chinese (Simplified and Traditional), English, Hindi, Korean, Tagalog and Vietnamese. Responses were collected from July 5, 2022, to Jan. 27, 2023, by Westat on behalf of the Center.

The survey included large enough samples of the Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese populations to report the findings for each group separately. These are the six largest origin groups among Asian Americans. These groups include those who identify with one Asian ethnicity only, either alone or in combination with a non-Asian race or ethnicity.

For more details about the survey used in this analysis, read the Methodology. For the questions used, read the Topline Questionnaire.

Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. The Center’s Asian American portfolio was funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts, with generous support from The Asian American Foundation; Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation; the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; the Henry Luce Foundation; the Doris Duke Foundation; The Wallace H. Coulter Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Long Family Foundation; Lu-Hebert Fund; Gee Family Foundation; Joseph Cotchett; the Julian Abdey and Sabrina Moyle Charitable Fund; and Nanci Nishimura.

We would also like to thank the Leaders Forum for its thoughtful leadership and valuable assistance in helping make this survey possible.

The strategic communications campaign used to promote the research was made possible with generous support from the Doris Duke Foundation.

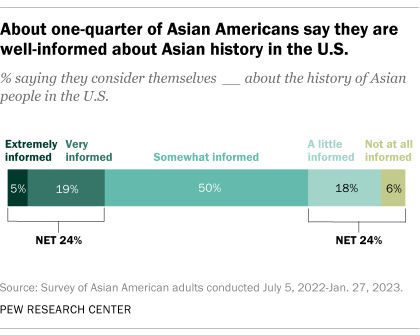

Just 5% of Asian Americans say they are extremely informed on this topic, and 19% say they are very informed. Half say they are somewhat informed, and another 24% say they are a little (18%) or not at all (6%) informed.

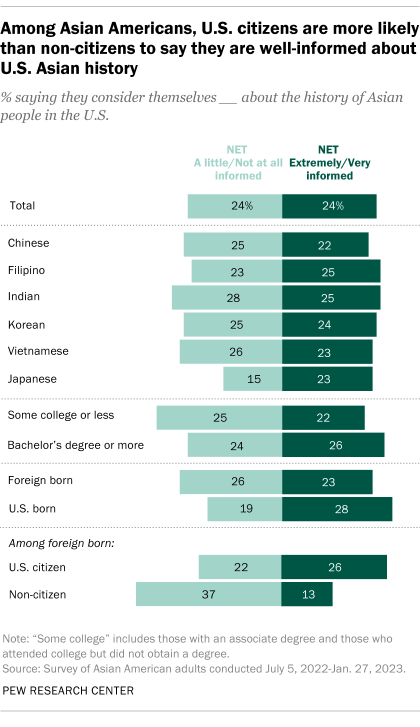

Knowledge of U.S. Asian history is relatively consistent across the United States’ six largest Asian origin groups. Between 22% and 25% of Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Korean, Vietnamese and Japanese Americans say they are well-informed about Asian history in the U.S.

Knowledge of this topic is also consistent across education levels: Asian Americans with at least a bachelor’s degree are about as likely as those without a college degree to be well-informed about U.S. Asian history.

On the other hand, some differences in knowledge emerge based on Asian Americans’ place of birth and citizenship, which sometimes overlap but are not the same.

Asian Americans who were born in the U.S. are slightly more likely than those who were born in other countries to be well-informed about U.S. Asian history (28% vs. 23%). And among Asian American immigrants, naturalized U.S. citizens are about twice as likely as non-citizens to be well-informed about it (26% vs. 13%).

Where Asian Americans learn about U.S. Asian history

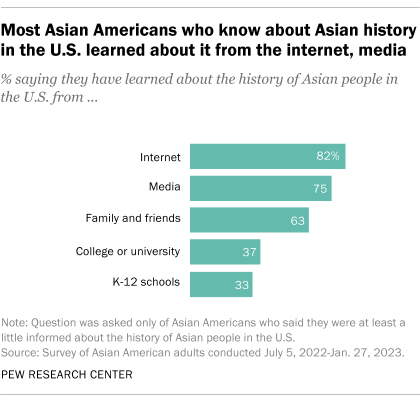

The survey also asked Asian Americans who said they are at least a little informed about U.S. Asian history whether they have learned about it from five sources: family and friends, K-12 schools, college or university, media, and the internet.

Majorities of Asian Americans say they have learned about U.S. Asian history informally – from the internet (82%), media (75%), and family and friends (63%). In contrast, fewer than four-in-ten have learned about it through formal education, including college or university (37%) and K-12 schools (33%).

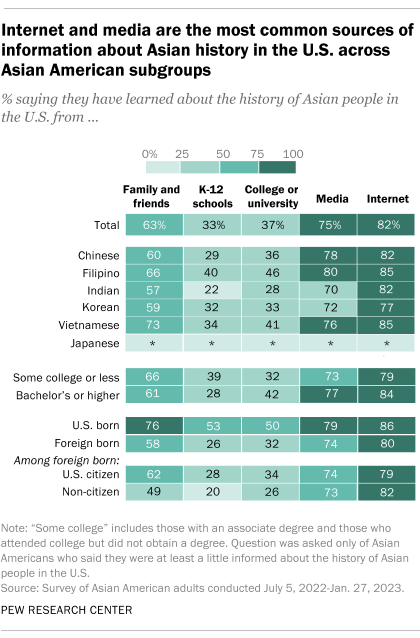

Among Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Korean and Vietnamese Americans, the internet and media are the most common ways of learning about U.S. Asian history. (The sample size for Japanese Americans on this question was too small to analyze separately.)

Chinese and Filipino Americans are especially likely to have learned about U.S. Asian history from the media, while Vietnamese Americans are especially likely to have learned about it from the internet or from family and friends.

While all of these origin groups are less likely to have learned about U.S. Asian history from formal education than from other sources, Indian Americans are particularly unlikely to get their information this way. Only 22% of Indian Americans say they learned about U.S. Asian history in elementary, middle or high school.

Asian Americans with a college degree or more education also tend to learn about U.S. Asian history from different sources than Asian Americans with less education. The internet and media are the most popular sources of information on U.S. Asian history for both groups, but Asian Americans with at least a bachelor’s degree are slightly more likely to have learned from these sources.

Some 84% of Asian Americans with a college degree or more have learned about U.S. Asian history from the internet, and 77% have learned about it from the media, compared with smaller shares of Asian Americans with less education (79% and 73%, respectively). In contrast, Asian Americans with some college education or less are more likely than their counterparts with college degrees to have learned about U.S. Asian history from family and friends and from K-12 schools.

Asian Americans who were born in the U.S. are more likely than those born outside the U.S. to have learned about U.S. Asian history from each of the five sources asked about in the survey. The difference is largest for K-12 schools: 53% of U.S.-born Asian Americans say they have learned about U.S. Asian history there, compared with 26% of foreign-born Asian Americans.

Somewhat different patterns appear for Asian American immigrants based on citizenship. Those who are naturalized U.S. citizens are more likely than non-citizens to have learned about U.S. Asian history from family and friends, K-12 education, and higher education. But they are about as likely as non-citizens to have learned about it from the internet and the media.

Note: Here are the questions used for the analysis, along with responses, and its methodology.