Census forms in the United States don’t ask about religion, but relatively few U.S. adults (25%) know this, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted shortly before census forms were mailed out in 2020.

Indeed, while the Census Bureau has long collected troves of data on Americans’ income, employment, race, ethnicity, housing and other things, the decennial census, held since 1790, has never directly asked Americans about their religion.

That’s not to say the census hasn’t gathered data about Americans’ faith backgrounds through other means from time to time. This analysis answers some basic questions about the often-debated place of religion in the census throughout much of U.S. history.

This article examines efforts by the Census Bureau to measure religious life in the United States and debates throughout American history on whether census forms should ask about religion.

It draws from academic articles; the Census Bureau’s website; and an appendix to Pew Research Center’s first Religious Landscape Study that was originally published in 2008.

The Center’s survey on the share of U.S. adults who knew the 2020 census form did not include a religion question was conducted Feb. 25 to March 9, 2020, among a sample of 3,456 U.S. adults. It was conducted by Ipsos Public Affairs in English and Spanish, using KnowledgePanel, its national representative online research panel. Here is the methodology for that survey.

Why doesn’t the census ask Americans about their religion?

Many critics have argued that making Americans identify their religion on a government form would go against long-held understandings of the separation between church and state. Some have worried that including such questions would deter people from filling out their census forms. Others, including heads of Jewish organizations in the U.S. in the decades after the Holocaust, expressed unease about the prospect of official counts of religious groups, fearing it could lead to antisemitism and allow for government tracking. Groups including Christian Scientists, some Baptist groups and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints also had objections.

Those who have favored adding a religion question have contended that official religion data would be useful to religious leaders, school planners, researchers and various civic groups.

After public debate over the issue in the 1960s and ’70s, the Census Bureau’s director, Vincent P. Barabba, announced in April 1976 that there would be no question on religion in the upcoming 1980 census, on the grounds that “asking such a question in the decennial census, in which replies are mandatory, would appear to infringe upon the traditional separation of church and [s]tate.” He added, “Regardless of whether this perception is legally sound, controversy on this very sensitive issue could affect public cooperation in the census and thus jeopardize the success of the census.”

A few months later, in October 1976, Congress officially forbade the bureau from asking about people’s “religious beliefs” or their “membership in a religious body” on the decennial census form that Americans are legally required to complete. The law allows the Census Bureau to ask Americans about religion in non-mandatory surveys – such as the bureau’s periodic population and household surveys – rather than the mandatory decennial census. These surveys have not asked questions designed to measure religious beliefs or identity, but the bureau has occasionally asked about things like religious service attendance, schools’ faith affiliations, and charitable donations to religious organizations. For example, the bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation has asked parents how often their children attended religious services, religious social events or religious school events in the previous year.

Has the Census Bureau ever directly asked Americans about their religion in surveys other than the decennial census?

Yes. In the mid-to-late 1950s, the Census Bureau tested a question on religious affiliation in the run-up to the 1960 census. The bureau’s director at the time, Robert W. Burgess, said he did not feel such a question would jeopardize the principle of separation of church and state and that it would not be any more intrusive than asking people about their education level.

In November 1956, the Census Bureau conducted a trial with a voluntary religion question for 431 households in Milwaukee. All but three of the households answered the question. After that, in March 1957, the bureau included a voluntary religion question on a broader national survey of 40,000 households (called the Current Population Survey). But privacy concerns and opposition from some religious groups that had experienced persecution in the U.S. ultimately prevented the bureau from including the question on the 1960 census form.

While the bureau did not include the question in 1960, it did publish some data from the 1957 survey, which elicited 35,000 responses. It found that two-thirds of people ages 14 and older identified as Protestant, about one-fourth were Catholic and a little more than 3% were Jewish. Overall, 96% reported an affiliation, while 2.7% reported no religion and 1% did not answer. But with some religious and public interest groups strongly opposing the question’s inclusion, the bureau decided to withhold fuller analysis of the data.

Has the Census Bureau ever gathered other information about religion in the U.S.?

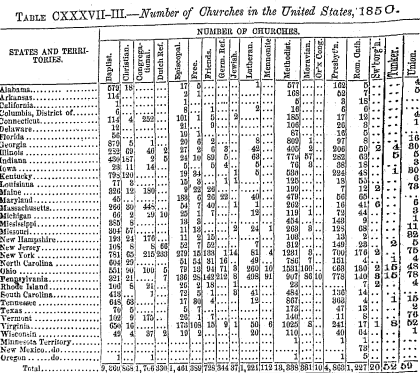

On five different censuses from 1850 through 1890, census takers collected data from faith leaders, including the number of churches in their community and how many members those churches had, as well as their seating capacities and property values. In 1850, a total of 38,183 congregations were tallied. (Christian and Jewish houses of worship alike were counted as “churches.”)

The form was modified over time. In 1870, for example, the number of religious organizations and church-owned buildings were each counted for the first time. The bureau defined “church” broadly, saying it “must have something of the character of an institution. It must be known in the community in which it is located. There must be something permanent and tangible to substantiate its title to recognition.”

Despite the bureau’s efforts to modernize its tabulation system, its expanded scope of inquiry had become costly and inefficient. The bureau exhausted its congressional appropriations before it could publish the full 1880 results, including the data on U.S. churches. (In addition, the census superintendent at the time, Charles W. Seaton, was said to be reluctant to release this data.) Religion questions were eventually phased out of the census schedules entirely.

That changed in 1906, when a separate decennial survey called the Census of Religious Bodies was conducted. Questionnaires mailed to religious leaders measured the number of churches, congregants and ministers, the size of Sunday school groups, the languages used to conduct worship services, and more. Lack of funding and incomplete data collection – due in part to religious freedom concerns and Depression-era dislocations – eventually led to the demise of the Census of Religious Bodies. Data was collected in 1946 but was never published.

Americans were not asked directly about their own religion in any of these censuses.

Does the Census Bureau still work with religious leaders or publish religion data?

Although clergy no longer submit denominational data to the bureau, many religious leaders do encourage their followers to send in their census forms. Faith leaders have worked to boost participation, including at a census-sponsored event in 2020 called the “Faith Community Census Weekend of Action.” In 2010, the bureau partnered with more than 34,000 religious leaders and groups. Informational materials were distributed at houses of worship that year, and faith-based partners promoted the census on local religion-focused radio shows.

The bureau still publishes county-level economic data on religious organizations in its County Business Patterns series. It also covers religious identity in its annual Statistical Abstract of the United States, based on data from outside sources.

Do other countries ask about religious identity in their national censuses?

Yes. More than a third of countries around the world have included religion data in their national censuses in recent decades. But they sometimes do not include categories for countries’ smaller minority faiths. And while some countries require respondents to share their religious affiliation in national censuses, it’s optional in other places, such as the United Kingdom.

Other countries have seen their own debates and developments around the issue. In 2020, for example, Tajikistan’s census included a religious identity question for the first time since 1937, which some argued violated religious freedom. And in 2015, Canada reinstated mandatory participation in its census – which has asked about religious affiliation since 1871.

If the Census Bureau doesn’t ask about it, how is religion measured in the United States?

Several nongovernmental organizations ask Americans about their religion in surveys with nationally representative samples. For example, Gallup has measured U.S. religious affiliation since 1948, and NORC, an independent research organization at the University of Chicago (formerly the National Opinion Research Center), has included religion questions in its General Social Survey since 1972. The National Congregations Study takes a different approach, conducting in-depth interviews with congregational leaders.

At Pew Research Center, we’ve been following trends in U.S. religion for decades. Our most ambitious project, the Religious Landscape Study (RLS), surveyed more than 35,000 people in all 50 states in both 2007 and 2014, asking Americans about their religious affiliation, beliefs and practices, and social and political views. The next RLS is currently in the works, planned for release in the coming years.