Jewish people were the targets of harassment in 94 countries in 2020, with incidents ranging from verbal and physical assaults to vandalism of cemeteries and scapegoating for the COVID-19 pandemic.

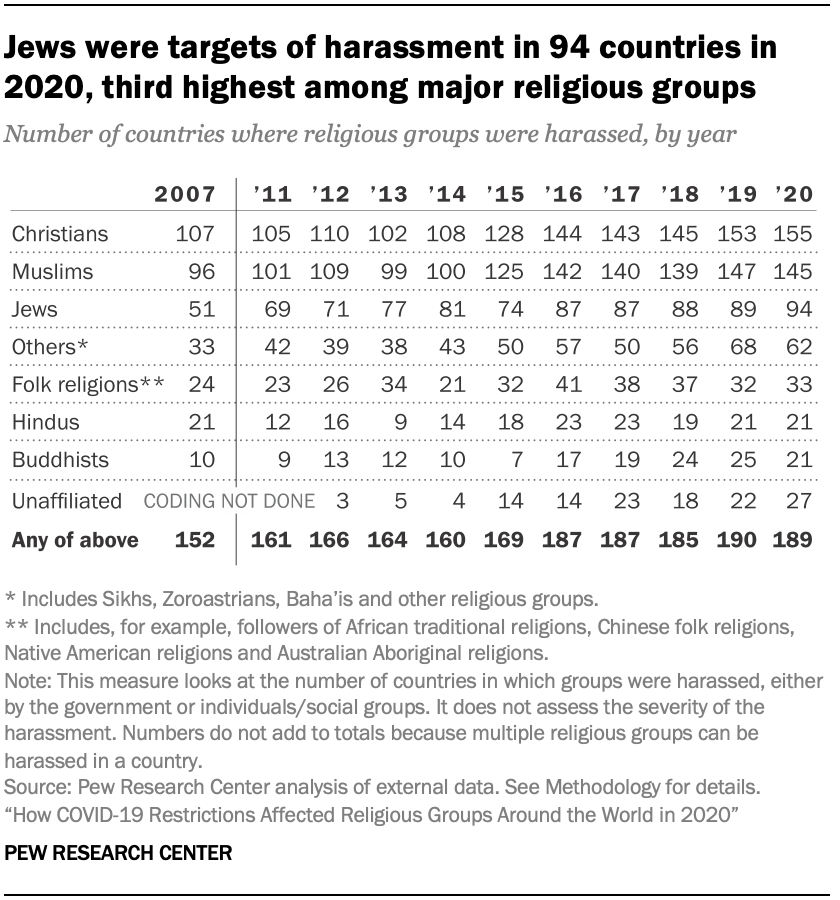

That was up from 89 countries the previous year, according to Pew Research Center’s latest annual study of global restrictions on religion, which tracks harassment by governments or social groups in 198 countries and territories. In the first year of the study, 2007, antisemitic incidents were documented in 51 countries.

In each year since, Jews have been a target of government restrictions or social hostilities involving religion in more countries than any other major religious group besides Christians and Muslims, even though only about 14.7 million people worldwide identify with the Jewish religion (about 0.2% of the world’s population). By comparison, there are nearly 2.4 billion Christians (31% of the global population) and roughly 1.9 billion Muslims (25%), according to the Center’s most recent figures.

This Pew Research Center analysis looks at the number of countries where there was at least one instance of anti-Jewish harassment by governments or social groups in 2020. It is based on data from the Center’s 13th annual report on religious restrictions, which examines the extent to which governments and societies around the world restrict religious beliefs and practices. The studies are part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world.

To measure global restrictions on religion in 2020 – the most recent year for which data is available – the study rates 198 countries and territories by their level of government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion. The new study is based on the same 10-point indexes used in the previous studies:

- The Government Restrictions Index (GRI) measures government laws, policies and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices.

- The Social Hostilities Index (SHI) measures acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society.

To track these indicators of government restrictions and social hostilities, Center researchers combed through approximately 20 publicly available, widely cited sources, including the U.S. Department of State’s annual Reports on International Religious Freedom and annual reports from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, as well as reports and databases from a variety of European and UN bodies, universities and several independent nongovernmental organizations.

For materials on harassment relating to the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers electronically searched English-language newspaper websites for each country and territory analyzed, using terms related to religious restrictions and COVID-19 to find relevant news articles. Coders also reviewed English-language global news sites and reports on COVID-19 produced by organizations including think tanks and university research centers.

Read the methodology for more details on sources used in the study.

The religious restrictions study defines government restrictions as laws, policies and actions by officials that restrict religious beliefs and practices. It defines social hostilities as acts by private individuals, organizations or groups.

In 2020, Jews were targets of either government restrictions or social hostilities (or both) in 41 of the 45 countries in Europe; 18 of 20 countries in the Middle East-North Africa region; 16 of 35 countries in the Americas; 16 of 50 countries in the Asia-Pacific region; and three of 48 countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

In Brazil, for example, a Jewish man had his teeth broken and his yarmulke torn with a pocketknife by men who told him “Hitler should have killed more Jews.” In Austria, a Jewish teen wearing a Star of David was attacked in the city of Graz after the assailants asked if he was Jewish. In Ukraine, a Jewish community center that also functions as a synagogue was damaged in a firebomb attack, while in Hungary and several other European countries, gravestones in Jewish cemeteries were vandalized.

In Iran, state-run media outlets published cartoons in 2020 that portrayed foreign officials as puppets of Jewish control, and government officials continued to question the history of the Holocaust. In Ecuador, government regulations, import taxes and paperwork obstructed Jews from importing kosher foods and products used in religious festivals. (Muslims faced similar problems importing halal foods.)

And in the United States, where more than 90 assaults against Jews in 2020 were reported by the FBI, a rabbi in Connecticut was assaulted and had his car stolen by two teenagers who yelled an antisemitic slur at him.

The Center’s annual study tracks restrictions on religion from year to year using a consistent set of approximately 20 publicly available sources, including reports by the U.S. State Department and the United Nations’ special rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief. The study also analyzes events tracked by university databases and publications by nongovernmental organizations such as Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and the International Crisis Group. The study relies on the sources’ determination of whether particular incidents targeted Jews.

Some of the anti-Jewish discourse observed in 2020 was related to the coronavirus pandemic. In the United Kingdom, for example, antisemitic conspiracy theories spread online, claiming that Jews used the coronavirus lockdowns to “steal everything.” In Italy, properties were vandalized with antisemitic posters and graffiti, including one incident in which a Star of David was depicted along with the words “equal to virus.” In Morocco, a man was arrested for social media posts in which he accused a Jewish citizen and a foreign national of infecting many people with COVID-19.

Incidents counted in the study also include anti-Jewish comments that appeared in media outlets. In Jordan, for example, a professor at al-Zaytoonah University said on a TV program that Jews were more dangerous than the coronavirus, AIDS, cholera and every other disease. And in Qatar, the newspaper al-Raya published an opinion piece saying Jews had accessed global power centers over the course of history and shaped decision-making, including the toppling of governments, to serve their own interests. The article was later removed from the website.

Several other religious groups have also faced harassment in an increasing number of countries since 2007, including Christians (155 countries in 2020 vs. 107 in 2007), Muslims (145 vs. 96) and Buddhists (21 vs. 10).

Countries are counted as experiencing harassment against members of a religious group if the source materials include at least one documented incident in the year being studied. The overall numbers help convey how geographically widespread harassment is, but they do not measure its severity. The Center’s report does not seek to determine which religious group faces the “most persecution” around the world.

Studies that measure antisemitism can take many different approaches. There are surveys that examine general attitudes toward Jews; surveys of Jews themselves about their perceptions and experiences; assessments of antisemitism in the media; and annual counts of incidents that target Jews. For example, Tel Aviv University’s Kantor Center for the Study of Contemporary European Jewry has published reports since 2000 on the number of antisemitic incidents around the world. It found a decrease in “bodily injuries” and damage to private property worldwide in 2020 compared with 2019, but an increase in antisemitic vandalism of cemeteries, Holocaust memorials and synagogues. During the period from 1989 to 2020, the number of violent antisemitic attacks worldwide was highest in 2009, according to the report.