Women make up more than a quarter (28%) of all members of the 118th Congress – the highest percentage in U.S. history and a considerable increase from where things stood even a decade ago.

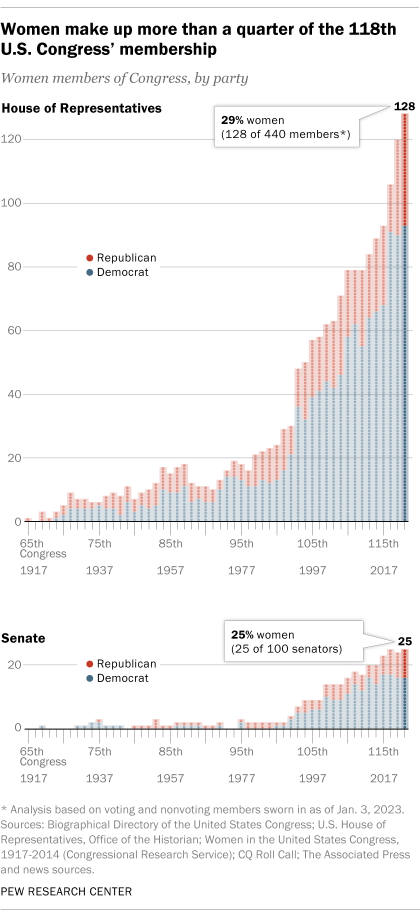

Counting both the House of Representatives and the Senate, women account for 153 of 540 voting and nonvoting members of Congress. That represents a 59% increase from the 96 women who were serving in the 112th Congress a decade ago, though it remains far below women’s share of the overall U.S. population. A record 128 women are serving in the newly elected House, accounting for 29% of the chamber’s total. In the Senate, women hold 25 of 100 seats, tying the record number they held in the 116th Congress.

The 2022 midterm elections sent nearly two dozen new congresswomen to the House, including Becca Balint, a Vermont Democrat who became both the first woman and openly LGBTQ person elected to Congress from the state. Of the 22 freshman representatives who are women, 15 are Democrats and seven are Republicans.

The Senate gained just one new female member: Republican Katie Britt, who became the first woman senator from Alabama.

Related: A record number of women are serving in the 117th Congress

This analysis builds on earlier Pew Research Center work to analyze the gender makeup of Congress. It includes voting and nonvoting members. Independent members of Congress are counted with the party they caucus with. Virginia’s 4th Congressional District seat, now vacant after Democrat Donald McEachin’s recent death, is excluded from the analysis.

For historical data on Congress, we used data from the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, the U.S. House of Representatives Office of the Historian, the Congressional Research Service’s “Women in the United States Congress, 1917-2014” and CQ Roll Call. For 2022 election results, we used data from Ballotpedia, The Associated Press and The New York Times, as well as news reports.

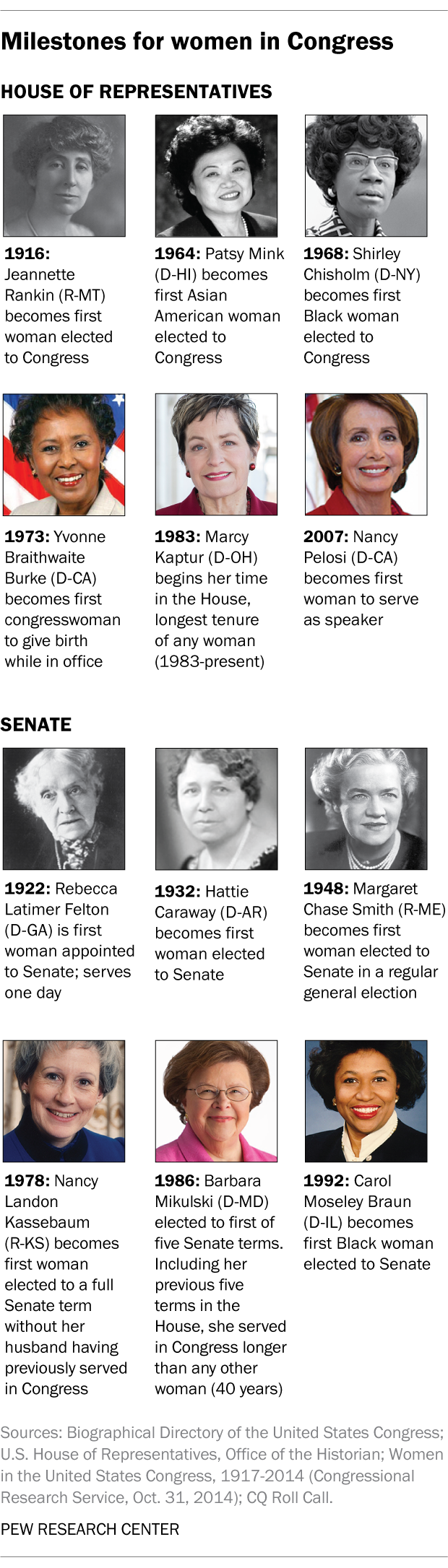

Many female incumbents who sought reelection this midterm cycle – 105 representatives and all five senators – kept their seats. Rep. Marcy Kaptur, D-Ohio, who first joined the House in 1983, retained her title as the longest-serving congresswoman in the chamber. California Rep. Nancy Pelosi, who’s served in Congress for 35 years and became the first female speaker of the House in 2007, also won reelection. But she announced she wouldn’t run for another leadership role after Republicans flipped control of the House.

Women make up a much larger share of congressional Democrats (41%) than Republicans (16%). Across both chambers, there are 109 Democratic women and 44 Republican women in the new Congress. Women account for 43% of House Democrats and 31% of Senate Democrats, compared with 16% of House Republicans and 18% of Senate Republicans. Still, the number of GOP women in the House is at its highest total yet: 35, up from 30 in January 2021, when the 117th Congress began.

The partisan gender division hasn’t always looked this way. Until the 1929 stock market crash, most of the dozen women elected to the House were Republicans, and for several decades afterward, the two parties’ numbers were generally close in that chamber. But the gap widened in the 1970s and has persisted, despite a temporary narrowing during the Reagan-Bush 1980s. Of the 261 women elected to the House in 1992 or later – including the newly elected group and those who were elected to the 117th Congress in special elections but not elected to full terms in the 118th – two-thirds (67%, or 176) have been Democrats, as have 27 of the 43 women (63%) who have served in the Senate since 1992.

The history of women in Congress

Women have been in Congress for more than a century. The first, Montana Republican Jeannette Rankin, was elected to the House in 1916, two years after her state gave women the vote. But women only began serving in more substantial numbers in the past few decades. More than two-thirds of the women ever elected to the House (261 of 381, including the incoming members of the 118th Congress) have been elected in 1992 or later.

The pattern is similar in the Senate: 43 of the 59 women who have ever served in the Senate – including the one new female senator – took office in 1992 or later.

The 19th Amendment, which extended voting rights to women across the nation, was ratified in 1920. That November, Alice Mary Robertson of Oklahoma became the first woman to defeat an incumbent congressman. (She lost the seat back to him two years later.) In 1922, veteran suffragist Rebecca Latimer Felton of Georgia was appointed to fill a vacant Senate seat; when Congress was unexpectedly called back into session, Felton was sworn in as the first female senator, though she only served for a day.

While women remained scarce in the Senate well into the 1980s, their numbers gradually, though not consistently, increased in the House – generally paralleling the expansion of women’s roles in broader society. In 1928, seven women were elected to the 71st Congress, a record at the time, and two more joined them later via special election. But that trend plateaued during the Great Depression and World War II. It wasn’t until after the war that the upward trajectory of women in Congress resumed, with 18 women serving in the House in 1961-63.

Although the 1970s saw prominent figures such as Barbara Jordan, Elizabeth Holtzman and Bella Abzug enter Congress, women’s overall numbers didn’t change much until 1981, when their House caucus exceeded 20 members for the first time. The big jump, however, came in 1992 – later dubbed “The Year of the Woman” – when four new female senators and 24 new congresswomen were elected. Academics have offered various explanations for why 1992 was such a breakthrough year for women in Congress, including an unusually large number of open seats due to redistricting and bank scandals, as well as backlash from the Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill hearings.

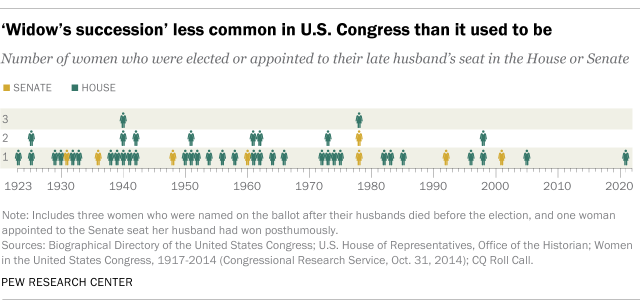

‘Widow’s succession’ in Congress

Well into the 1970s, one of the most common ways for a woman to enter Congress was by succeeding her deceased husband or father, either by election or appointment. Of the 90 women who served in the House between 1916 and 1980, 31 were initially elected to their husband’s seat after he died; three were chosen to replace their husbands on the ballot when the men died before Election Day; and one, Winnifred Mason Huck of Illinois, was elected in 1922 to fill the last four months of her late father’s term. (Another early congresswoman, Katherine Gudger Langley of Kentucky, won her husband’s seat back in the next election in 1926 after he resigned following his conviction for violating Prohibition laws.)

Like Langley, most of the holders of these so-called “widow’s succession” seats stayed in Congress for only a term or two. But some went on to distinguished careers on Capitol Hill. Margaret Chase Smith of Maine, for instance, won a special election in 1940 to fill the last seven months of her husband’s term. Smith went on to win four full House terms on her own, then was elected to four terms in the Senate, thereby becoming the first woman to serve in both chambers. Lindy Boggs, who was elected to her husband’s seat in 1973 after he was presumed killed in a plane crash, served nearly 18 years. She later was named U.S. ambassador to the Holy See.

Six of the 14 women senators who served before 1980 were either elected or appointed to fill their late husbands’ seats. Of those, two (Hattie Caraway of Arkansas and Maurine Brown Neuberger of Oregon) subsequently won full terms in their own right.

Rep. Julia Letlow, R-La., who was reelected this fall, became the most recent widow to serve out her husband’s term in the House. She won a special election in 2021 after Luke Letlow died from COVID-19 complications shortly before swearing into office.