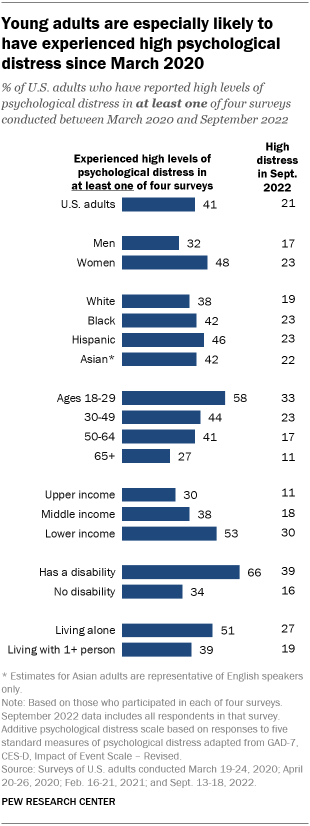

At least four-in-ten U.S. adults (41%) have experienced high levels of psychological distress at least once since the early stages of the coronavirus outbreak, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis that examines survey responses from the same Americans over time.

Experiences of high psychological distress are especially widespread among young adults. A 58% majority of those ages 18 to 29 have experienced high levels of psychological distress at least once across four Center surveys conducted between March 2020 and September 2022.

This assessment of the public’s psychological reaction to the COVID-19 outbreak is based on surveys of members of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) conducted online several times since March 2020. The mental health questions were included on four surveys. The first survey was conducted among 11,537 U.S. adults March 19-24, 2020; a second survey with the question series was conducted April 20-26, 2020, with a sample of 10,139 adults; a third survey was conducted February 16-21, 2021, among 10,121 adults; and the most recent survey was conducted September 13-18, 2022, among 10,588 adults. Additionally, researchers analyzed a subsample of 5,007 respondents who participated in each of the four surveys to examine psychological distress over time.

The ATP is an online survey panel that is recruited through national random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The surveys are weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. The group of respondents who participated in each of the four surveys was similarly weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population. Here is more information about the ATP.

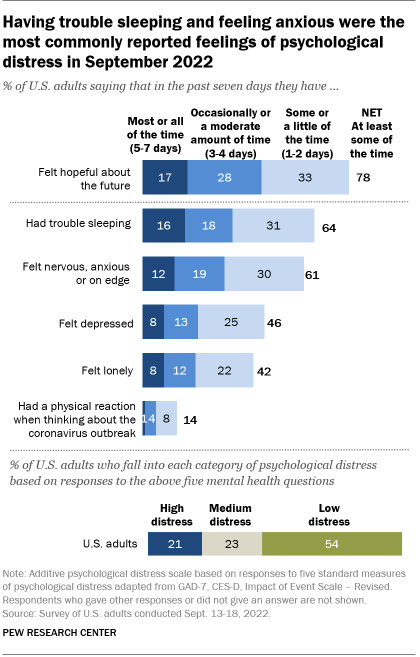

The psychological distress index used here measures the total amount of mental distress that individuals reported experiencing in the past seven days, as captured by questions measuring sleeplessness, anxiety, depression, loneliness, and physical reactions experienced when thinking about the outbreak. The low distress category includes about half of the sample; very few in that group said they were experiencing any of the types of distress most or all of the time. The middle category includes roughly a quarter of the sample, while the high distress category includes 21%. A large majority of those in the high distress group reported experiencing at least one type of distress most or all of the time in the past seven days.

This research benefited from the advice and counsel of the COVID-19 and mental health measurement group from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH): Catherine K. Ettman (JHSPH); M. Daniele Fallin (JHSPH, now at Emory University); Calliope Holingue (Kennedy Krieger Institute, JHSPH); Renee Johnson (JHSPH); Luke Kalb (Kennedy Krieger Institute, JHSPH); Frauke Kreuter (University of Maryland, Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich); Elizabeth Stuart (JHSPH); Johannes Thrul (JHSPH); and Cindy Veldhuis (Columbia University, now at Northwestern University).

Here are the mental health questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and the detailed survey methodology statements for surveys conducted in March 2020, late April 2020, February 2021 and September 2022.

The analysis highlights the fluid nature of psychological distress among Americans, as measured by a five-item index that asks about experiences such as loneliness, anxiety and trouble sleeping.

In the September 2022 survey, 21% of U.S. adults fell into the high psychological distress category; in each of four surveys, no more than 24% of adults have fallen into this category. But because individuals experience varying levels of distress at different points in time, a significantly larger share of Americans (41%) have experienced high psychological distress at least once across the four surveys conducted over the past two and a half years.

In addition to age, experiences of high psychological distress are strongly tied to disability status and income. About two-thirds (66%) of adults who have a disability or health condition that keeps them from participating fully in work, school, housework or other activities reported a high level of distress at least once across the four surveys. And those with lower family incomes (53%) are more likely than those from middle- (38%) and high-income households (30%) to have experienced high psychological distress at least once since March 2020.

While many Americans faced challenges with mental health before the coronavirus pandemic, public health officials warned in early 2020 that the pandemic could exacerbate psychological distress. The negative effects of the outbreak have hit some people harder than others, with women, lower-income adults, and Black and Hispanic adults among the groups who have faced disparate health or financial impacts.

Americans’ personal levels of concern about getting or spreading the coronavirus have continued to decline over the course of 2022. The coronavirus is one of many potential sources of stress, including the economy and worries about the future of the nation.

Psychological distress levels have shifted for most Americans during the pandemic

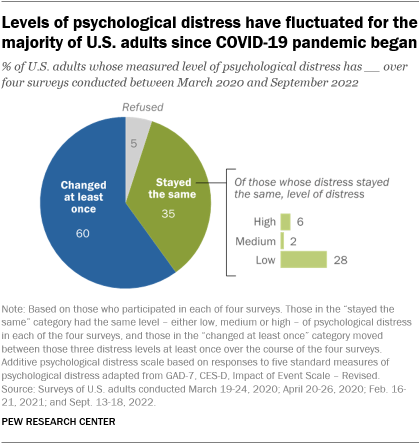

Amid the shifting landscape of COVID-19 in the United States, just 35% of Americans have registered the same level of psychological distress – whether high, medium or low – across all four surveys conducted by the Center since March 2020.

Instead, a majority of respondents (60%) moved in and out of levels of psychological distress. Psychological distress increased for some but decreased for others. One illustration of the fluid nature of these experiences is that while 41% of U.S. adults faced high psychological distress at least once across four surveys, just 6% experienced high distress in all four surveys. Nearly five times as many (28%) experienced low distress in all of the surveys.

The index of psychological distress is based on measures of five types of possible distress experienced in the past week, such as anxiety or sleeplessness, that are adapted from standard psychological measures. As used in the current survey, the questions are not a clinical measure nor a diagnostic tool; they describe people’s emotional experiences during the week prior to the interview.

Only one question refers specifically to the coronavirus outbreak. It asks how often in the past week Americans have “had physical reactions, such as sweating, trouble breathing, nausea, or a pounding heart” when thinking about their experience with the coronavirus outbreak. In the most recent September survey, 14% of Americans answered this question affirmatively. In March 2020, in the early stages of the outbreak, 18% said they had experienced this.

Trouble sleeping is one of the most common forms of distress measured in the surveys. In the latest survey, about two-thirds of adults (64%) reported trouble sleeping at least some or a little of the time during the past week. A similar share (61%) said they had felt nervous, anxious or on edge.

Experiences with depression and loneliness also register with sizable shares of Americans. In the most recent survey, 46% of adults said they had felt depressed at least one or two days during the past week, and 42% said they had felt lonely.

All four surveys have included a question about positive feelings, though it is not part of the psychological distress index. Overall, 78% of U.S. adults said they had felt hopeful about the future at least one or two days in the past week, according to the latest survey from September. However, 22% of adults said they had felt hopeful about the future rarely or none of the time during the past week.

Note: Here are the mental health questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and the detailed survey methodology statements for surveys conducted in March 2020, late April 2020, February 2021 and September 2022.