Today, Pew Research Center is releasing results of 66 focus group discussions with Asian American adults. While the Center has been studying racial and ethnic identity for some time, this project represents the Center’s first comprehensive examination of Asian American identity using focus groups.

In this Q&A, we speak with Neil G. Ruiz, associate director of race and ethnicity research at the Center, to learn why and how researchers conducted these focus groups. We also explore a few broader questions about what it means to be Asian in America today. All answers have been lightly edited for clarity and concision.

What was the purpose of this study?

At Pew Research Center, we’re committed to providing a more complete picture of all people who live in the United States. One reason for doing this study is that there has been a major data gap on Asian Americans in the world of survey research. We also know that Asian Americans are a diverse and growing population. We conducted this project to capture the diverse voices and experiences of Asian Americans and understand what it means to be Asian in America.

Pew Research Center is known for its surveys. Why did you conduct focus groups with Asian Americans, instead of fielding a survey?

This study aims to expand the depth and breadth of our understanding of racial and ethnic identity by asking Asian Americans to describe their attitudes and experiences in their own words, without preset response options. It’s worth noting that this is not the first time the Center has conducted focus groups in the U.S. We’ve also done this with other populations – most recently, trans and nonbinary Americans.

This study aims to expand the depth and breadth of our understanding of racial and ethnic identity by asking Asian Americans to describe their attitudes and experiences in their own words, without preset response options.

Another reason for using focus groups is that it’s virtually impossible to use traditional survey methods to capture the attitudes of some subgroups within the U.S. Asian population. Overall, Asian Americans account for only about 7% of the U.S. population, and within that 7% are much smaller subgroups, including Bhutanese, Hmong and Laotian Americans, who each make up 2% or less of all Asians living in the United States.

Also, many Asian Americans are immigrants who hail from countries with a wide range of languages and culture. That means it would be costly to create a written survey that can be taken in so many different languages. For these reasons and others, it remains a challenge to survey Asian Americans with traditional survey methods.

How were the focus groups conducted?

We conducted our focus groups over the course of nearly three months – from Aug. 4 to Oct. 14, 2021. Due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, all focus groups were conducted virtually.

Each focus group lasted 120 minutes and was moderated by someone who self-identified as a member of the same racial or ethnic group as the participants and was fluent in the language spoken by our immigrant participants. For all focus groups consisting of U.S.-born participants, moderators conducted the interviews in English. Moderators followed a guide we developed to prompt conversations.

Who participated in the focus groups?

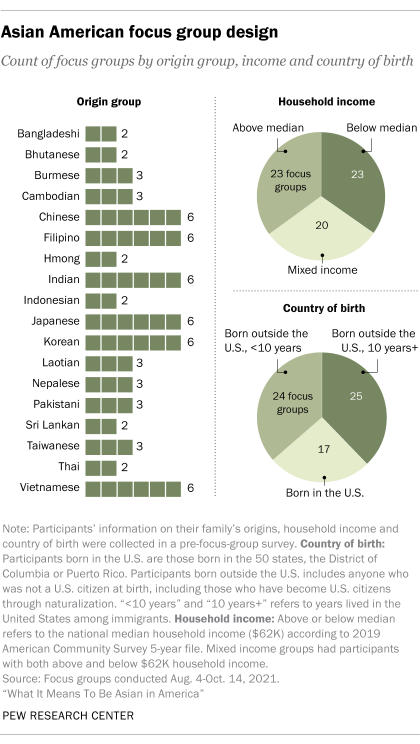

Each focus group included four participants, for a total of 264 interviewees. The participants hailed from all over the U.S. and represented each of the 18 largest Asian ethnic origin groups in the country, as measured by the Census Bureau. These included Chinese, Indian, Filipino, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese people – the six largest Asian origin groups in the U.S., which together make up about 85% of all Asians living in the country. They also included participants who are Bangladeshi, Bhutanese, Burmese, Cambodian, Hmong, Indonesian, Laotian, Nepalese, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Taiwanese and Thai. These 12 smaller origin groups account for less than 15% of the nation’s Asian population.

We further sorted our focus groups by nativity – that is, whether participants were born in another country or born in the United States. For immigrant participants, we grouped them by how long they have lived in the U.S. – more or less than a decade. We also grouped participants by their household income – above or below $62,000 a year, the median household income of the overall population in the U.S. We did this in part because there is so much variation in household income among Asian Americans.

What were some of the specific topics that came up in the focus groups?

The focus group discussions centered on the experience of living in the United States. For focus groups with participants who were born abroad, we asked about their immigration or refugee experiences. For those with U.S.-born participants, we explored issues including how their experiences in school have shaped their identity and how they have navigated the concepts of “fitting in” or “standing out.”

In all focus groups, we had extensive discussions about how participants choose to identify racially or ethnically, what kinds of experiences (if any) they have had with discrimination, their experiences with finding employment and, in general, the challenges associated with being Asian in the U.S., such as learning English for immigrants. We also discussed the way Asian Americans are represented in popular culture and politics.

Did discrimination as a result of COVID-19 pandemic come up in these discussions?

Yes, it did come up. Some focus group participants mentioned being mistaken for Chinese and blamed for the pandemic, which reminded them of prior experiences of being mistaken for someone from another ethnic or racial background.

But a number of participants in different focus groups also mentioned that this was not the first time they’ve encountered discrimination in the U.S. Some mentioned discrimination in a variety of other scenarios, including in their personal lives, workplaces and everyday street encounters even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Focus groups tend to be more qualitative than quantitative research. Were you able to gather any data from this project?

While it’s true that focus groups are primarily a form of qualitative research, they can be supplemented by quantitative methods. For this project, our researchers reviewed focus group transcripts and coded them using ATLAS.ti, a qualitative data analysis and research software. All told, we coded 7,920 minutes of discussion.

We used ATLAS.ti to summarize participants’ responses to the questions they were asked, using coding schemes to highlight key themes and points of interest in the conversations, as well as the dynamics of the discussion. For example, we coded topics and subtopics to identify the factors shaping identity among our respondents.

We took particular care to ensure that the viewpoints expressed in our report accurately captured the range of opinions expressed by our focus group participants – emphasizing not just majority opinions, but minority opinions as well.

This exercise allowed us to use ATLAS.ti to sort and display all the relevant quotes from the focus groups for the specific topics being analyzed, as well as identify the demographic characteristics of those who said them. We took particular care to ensure that the viewpoints expressed in our report accurately captured the range of opinions expressed by our focus group participants – emphasizing not just majority opinions, but minority opinions as well.

How did you define “Asian” for the purposes of this study?

In this project, we use the terms “Asian,” “Asian American” and “Asians living in the United States” interchangeably. These terms all refer to U.S. adults who self-identity as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic identity. These definitions are based on the system used by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Why did you cover only Asian Americans and not Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders?

The story of Asians in the U.S. is largely a story of immigration. The story of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, by contrast, is a story of America coming to them.

Also, since Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders include even less populous groups than are found among Asian Americans, we wanted to make sure we are able to highlight their experiences on their own terms, rather than risk having them be hidden within the broader grouping of “Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.”

What is ethnicity, and how is it different from race?

The Census Bureau defines race as a person’s self-identification with one or more social groups. On the official census form, an individual can report being White, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, or some other race.

Ethnicity, by contrast, is used to measure whether an individual has Hispanic origin, which is independent from racial categories. Ethnicity in the context of Asian American research refers to the ethnic origin of an individual, which may be viewed as the heritage, nationality, lineage or country of birth of the person – or the person’s parents or ancestors – before arriving in the U.S.

Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder.

This project was funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts, with generous support from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation; the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; the Henry Luce Foundation; The Wallace H. Coulter Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Long Family Foundation; Lu-Hebert Fund; Gee Family Foundation; Joseph Cotchett; the Julian Abdey and Sabrina Moyle Charitable Fund; and Nanci Nishimura.

The related video clips and video documentary were made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts, with generous support from The Sobrato Family Foundation and The Long Family Foundation.

We would also like to thank the Leaders Forum for its thought leadership and valuable assistance in helping make this study possible.