The summer of 2021 was the strongest in years for U.S. teenagers seeking work. Beset by labor shortages, businesses trying to come back from the COVID-19 pandemic hired nearly a million more teens than in the summer of 2020.

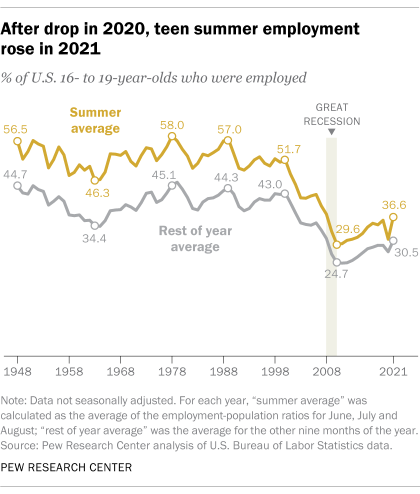

Overall, more than 6 million U.S. teens, or 36.6%, had a paying job for at least part of last summer, marking the highest teen summer employment rate since 2008, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accommodation and food services, arts and recreation, and manufacturing were among the sectors leading the teen hiring surge.

Many economists are predicting another strong job market for teens this summer. If that pans out, it would continue a turnaround from the low-water mark of 2010 and 2011 and suggest that the plunge in teen employment during the first pandemic summer of 2020 was an anomaly.

To understand what’s happened to teen summer employment, Pew Research Center relied on monthly employment data gathered by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. We specifically looked at the employment rate – or, more formally, the employment-population ratio – for 16- to 19-year-olds, which the BLS has compiled since 1948. We took the average employment rate for June, July and August of each year as our measure of summer employment.

In addition, we analyzed unpublished BLS data on industry and occupational employment among 16- to 19-year-olds for July 2021.

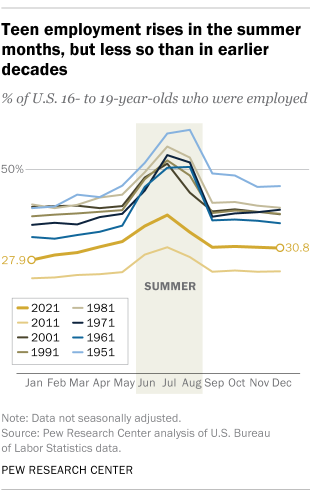

In both cases, we used nonseasonally adjusted data for this analysis, as teen employment normally rises sharply in the summer months and typically peaks in July.

That summer, fewer than a third of U.S. teens (30.8%) had a paying job, as many of the places most likely to employ them – restaurants, shops, recreation centers, tourist attractions – were either shuttered entirely or had their operations severely curtailed because of the pandemic.

By the summer of 2021, many of those same employers were almost literally begging for workers. And this year, many adults still have not reentered the job market. While the employment-population ratio for people ages 20 and older has yet to reach its pre-pandemic level, that ratio for 16- to 19-year-olds rebounded quickly and has even grown a bit since early 2020.

Still, teen summer employment remains well below where it was before the turn of the 21st century. From 1948, when the current data series begins, through 2000, roughly half (or even more, in some years) of U.S. teens on average could expect to spend at least part of their summer vacation lifeguarding, waiting tables, running the Tilt-a-Whirl or otherwise working for pay. As recently as 2000, the average teen summer employment rate was 51.7%.

The share of teens working during the summer fell during the dot-com implosion of the early 2000s and dropped even more sharply during and after the 2007-09 Great Recession. By 2010 and 2011, the teen summer employment rate had bottomed out at 29.6%. The latter year, fewer than 5 million teens reported working over the summer, the lowest number since 1959.

Teen summer employment recovered, slowly, in subsequent years, with the employment rate inching up to 35.8% by the summer of 2019. The pandemic appears to have dented, but not fundamentally altered, that gradual upward trend.

Data so far this year, as well as more anecdotal evidence, suggests that this could be another strong summer for teens looking to earn some money. In May, about 5.5 million 16- to 19-year-olds were employed (not adjusting for seasonal variations) – 145,000 more than in May 2021, though because of population growth the employment rate was slightly lower (32.1% in May 2022, 32.4% in May 2021). An estimated 631,000 teens were unemployed last month, meaning they were available and actively searching for work but hadn’t yet found any. The unemployment rate among this age group was 10.3%, versus 9.5% a year earlier.

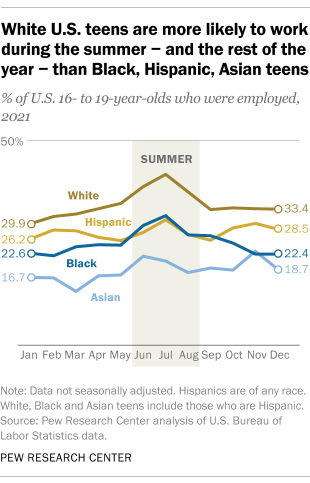

White teens are more likely to work in the summer, as well as during the rest of the year, than teens of other racial and ethnic backgrounds – a trend the pandemic did nothing to change. On average last summer, almost four-in-ten White teens (39.5%) were employed, compared with 29.4% of Black teens, 28.6% of Hispanic teens and 20.2% of Asian teens.

Older teens continued to be considerably more likely to work than their younger peers. Last summer’s average summer employment rate for 18- and 19-year-olds was 47.1%, compared with 26.9% for 16- and 17-year-olds.

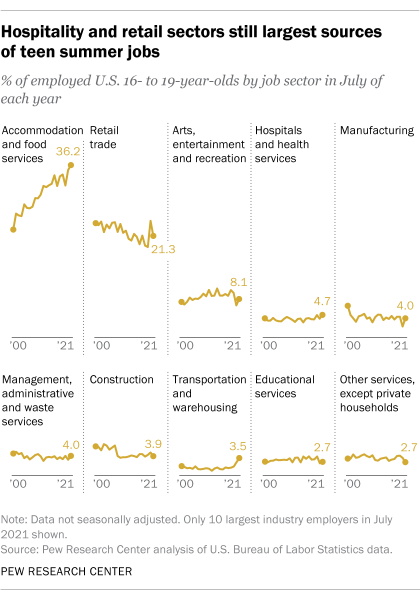

The greatest number of employed teens last summer – 2.3 million, or 36.2% of all employed teens – worked in the accommodation and food services industry, which has been the largest employer of teens for the past two decades. That industry, which includes hotels and motels, resorts, restaurants, snack shacks and similar establishments, also had the biggest increase in teen jobs between summer 2020 and summer 2021, accounting for 41 of every 100 newly created teen jobs.

Before 2001, retail was the biggest employer of teens in the summer. The industry has been slowly declining as a source of teen summer jobs, despite a bump up in 2020. Still, last summer nearly 1.4 million teens (21.3%) worked behind a cash register or on a sales floor.

Some 516,000 teens worked last summer in arts, entertainment and recreation – a varied industry that includes everything from minor league baseball to summer-stock theater to amusement parks. That was 156,000 more than in summer 2020, making this one of the industries that saw the most jobs added between summer 2020 and summer 2021. Manufacturing, which saw a steep drop in teen summer employment in 2020, rebounded strongly last summer, more than doubling its teen payroll to 257,000.

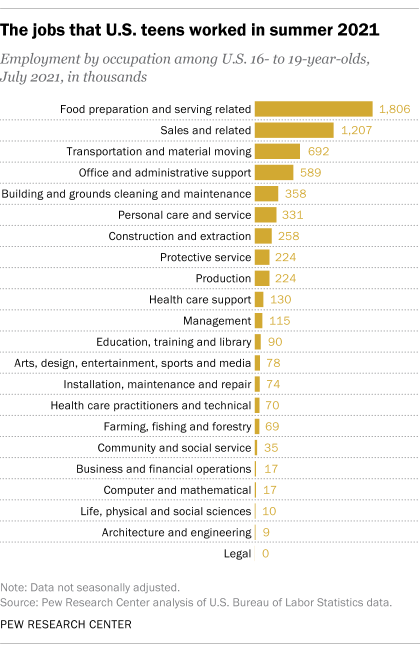

Looking occupationally rather than by industry, female teens were more likely than male teens to work in the two largest job categories: food preparation and serving (32.2% of female teens vs. 24.3% of male teens) and sales (22.8% vs. 14.9%), as well as in office and administrative support and personal care and services. Male teens were more likely to have jobs in transportation and material moving (16.3% of male teens, 5.2% of female teens) and construction and extraction (8% vs. less than 1%), as well as building and grounds maintenance, protective service and production occupations.

The long-term decline in teens working during the summer is a specific instance of a broader long-term decline in overall youth employment, a trend that’s also been observed in other advanced economies.

Researchers have suggested multiple reasons why this might be happening: fewer low-skill, entry-level jobs, such as sales clerks or office assistants, than in decades past; more schools ending later in June and/or restarting before Labor Day; more students enrolled in high school or college over the summer; more teens doing volunteer community service as part of their graduation requirements or to burnish their college applications; and more students taking unpaid internships, which the Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t count as being employed.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published July 2, 2018, and last updated on June 7, 2021.