Nearly nine-in-ten Black Americans say they are at least somewhat informed about the history of Black people in the United States, with family and friends being the single largest source of information about it, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey of Black adults.

This analysis is from Pew Research Center’s second in-depth survey of public opinion among Black Americans (read the first, “Faith Among Black Americans”). It provides a robust opportunity to examine the rich diversity of Black people in the United States. The survey explores differences based on the importance of Black identity to Black Americans, between U.S.-born Black people and Black immigrants, between Black people who live in different regions, and those of different ethnicities, party affiliations, ages and income statuses.

The online survey of 3,912 Black U.S. adults was conducted Oct. 4-17, 2021. The survey includes 1,025 Black adults on Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) and 2,887 Black adults on Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel. Respondents on both panels are recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses.

Recruiting panelists by phone or mail ensures that nearly all U.S. Black adults have a chance of selection. This gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole population (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling). Here are the questions used for the survey of Black adults, along with responses, and its methodology.

The achievements of Black Americans are recognized every February during Black History Month, which traces its roots to an exhibition commemorating their emancipation from slavery.

The historical origins of Black History Month

Black History Month has its origins in a Black history display that Carter G. Woodson created in 1915 for an exhibition honoring the 50th anniversary of Black Americans’ emancipation from slavery. Woodson wanted the celebration of Black American freedom and achievement to continue beyond the exhibition, so he founded several intellectual and cultural endeavors: the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915, the Journal of Negro History in 1916, and ultimately Negro History Week in 1926.

Woodson selected February for Negro History Week to align with previously established Black American celebrations of both Frederick Douglass’ and Abraham Lincoln’s birthdays. Fifty years after its founding, Negro History Week was expanded to Black History Month in 1976 by the organization Woodson founded, now known as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

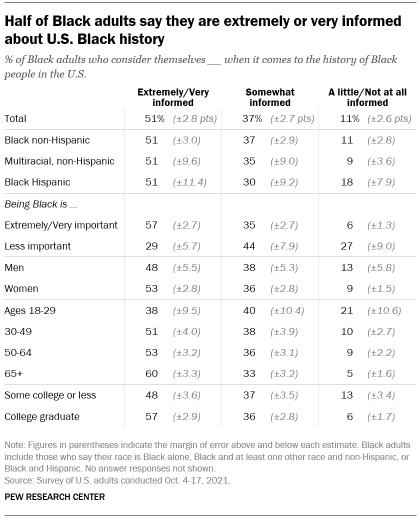

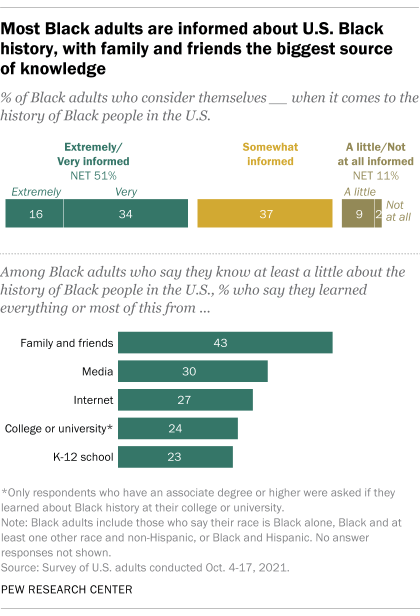

About half of Black Americans (51%) say they are very or extremely informed about the history of Black people in the U.S. Nearly four-in-ten (37%) say they are somewhat informed, while 11% say they are a little or not at all informed.

Among Black adults who identify as Black alone, 51% say they are very or extremely informed about U.S. Black history. An identical share of multiracial (51%) adults say the same. About half of U.S.-born Black adults (51%) and Black immigrants (50%) also say they are very or extremely informed about U.S. Black history.

There are notable differences among Black adults in how well informed they say they are when it comes to U.S. Black history. Black adults who say being Black is highly important to their identity are almost twice as likely as those who say being Black is less important (57% vs. 29%) to say they are very or extremely informed about the history of Black people in the U.S.

In addition, Black adults ages 30 and older are more likely than those under 30 to say that they are very or extremely informed.

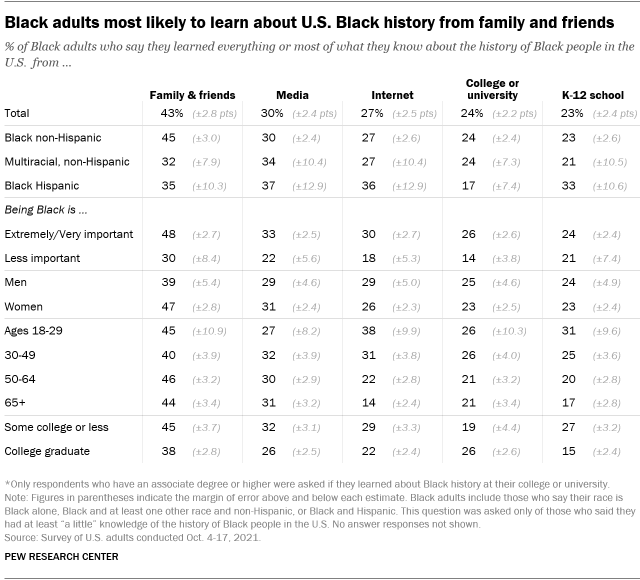

Black Americans who know at least a little about U.S. Black history say they learned about it in many different ways. The most common way is from family and friends, with 43% saying they learned everything or most of what they know about Black history from those close to them. (See detailed tables below for more on how subgroups of Black Americans rate their knowledge of Black history and where they learned about it.)

Smaller shares say they learned about U.S. Black history from the media (30%), the internet (27%) and K-12 schools (23%). For those with at least an associate degree, 24% say they learned about U.S. Black history from higher education.

Views of one’s own racial identity can influence how Black Americans learn about U.S. Black history. The share of Black Americans who say they learned this history from family and friends reaches 48% among those who say being Black is a very or extremely important part of their identity, compared with just 30% among those who say being Black is less important to their identity. Black Americans who say being Black is an important part of their identity are also more likely to have learned about Black history from the media (33% vs. 22% who say being Black is less important to them), internet (30% vs. 18%) and higher education (26% vs. 14%), for those with at least an associate degree.

Black adults under age 30 (38%) and ages 30 to 49 (31%) are more likely than those 50 to 64 (22%) and 65 and older (14%) to say they learned everything or most things they know about Black history from the internet. Black adults under 30 (31%) and ages 30 to 49 (25%) also are more likely than those 50 to 64 (20%) and 65 and older (17%) to say they learned all or most of what they know about their history from K-12 schools.

Non-Hispanic Black adults (45%) are more likely than Black multiracial adults (32%) to say they learned everything or most things they know about Black history from their family and friends. While U.S.-born Black adults (44%) and Black immigrants (36%) are similarly likely to rely on family and friends as sources, Black immigrants are more likely than U.S.-born Black adults to have learned about Black history from the media (45% vs. 29%) and the internet (40% vs. 26%).

Note: Here are the questions used for the survey of Black adults, along with responses, and its methodology.