Research has suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic has had greater impacts on women in the economy and the home. In this period of turmoil, women also may be carrying a heavier emotional burden than men, according to a Pew Research Center survey.

The Center recently asked Americans about their thoughts and feelings regarding human suffering in light of the pandemic and other recent tragedies, finding that women and men answered a few questions somewhat differently.

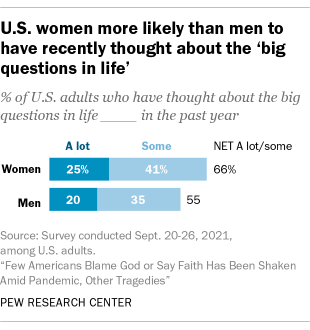

Two-thirds of women (66%) say that in the past year, they have personally thought “a lot” or “some” about big questions such as the meaning of life, whether there is any purpose to suffering and why terrible things happen to people, compared with 55% of men who report the same.

For this analysis – part of a broader look at how Americans make sense of suffering and bad things happening to people – we surveyed 6,485 U.S. adults from Sept. 20 to 26, 2021. All respondents to the survey are part of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education, religious affiliation and other categories. For more, see the ATP’s methodology and the methodology for this report.

The questions used in this report can be found here. Here are details on how the Center asks about gender.

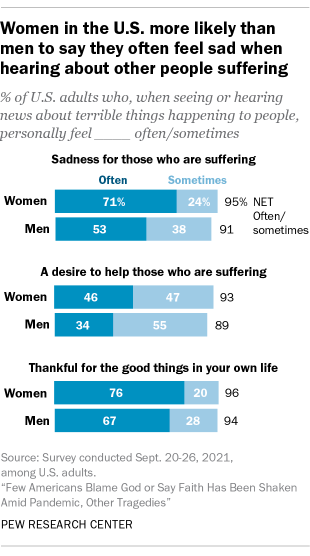

When seeing or hearing about terrible things happening to people, women are much more likely than men (71% vs. 53%) to say they often feel sad for those who are suffering. Similarly, a larger share of women (46%) than men (34%) report often feeling the desire to help those suffering. And when hearing about bad news, women are more inclined than men to say they often feel thankful for the good things in their own lives (76% vs. 67%).

While women are more inclined than men to report having these feelings often, overwhelming majorities of men do say they experience these things at least “sometimes.”

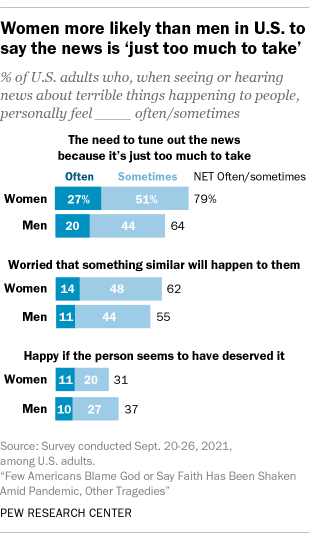

In response to terrible news, women also mention feeling news fatigue more frequently than men. Around a quarter of women (27%), compared with a smaller share of men (20%), often feel the need to tune out the news because it’s just too much to take. And 79% of women – versus 64% of men – say they at least sometimes feel this way. The Center found a gender gap in the same direction on a similar question about news fatigue in 2019.

Upon learning of recent tragedies, women are also somewhat more likely than men to say they often or sometimes feel worried that something similar will happen to them (62% vs. 55%). Meanwhile, men are slightly more inclined than women to confess they often or sometimes have feelings of schadenfreude – feeling happy “if the person [who is suffering] seems to have deserved it” (37% vs. 31%).

Does all this mean that women innately feel more empathy than men? Some research points in that direction, but other scientists urge caution in attributing gender differences to biology.

Gender gaps in belief in the afterlife, supernatural

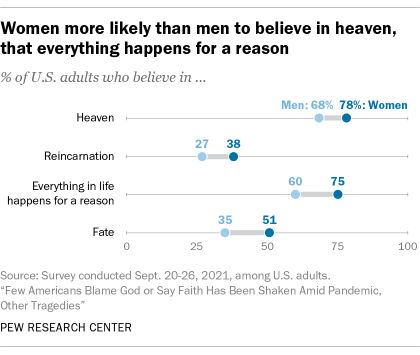

The survey also finds that women are much more likely than men to believe in an afterlife and supernatural forces.

Three-quarters of women, for instance, believe that everything in life happens for a reason, compared with six-in-ten men. Similarly, women are much more likely than men (51% vs. 35%) to believe in fate – that is, that the course of their lives is predetermined.

Meanwhile, nearly eight-in-ten women in the U.S. (78%) say they believe in heaven, a full 10 percentage points higher than the share among men. And women are more likely to express belief in reincarnation as well (38% vs. 27%).

These findings reflect the fact that in general, women are more religious than men by a variety of measures. For example, among U.S. adults, women are substantially more likely than men to consider religion very important in their lives.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.