The COVID-19 recession resulted in a steep but transitory contraction in employment, with greater job losses among women than men. The recovery began in April 2020 and is not complete. As of the third quarter of 2021, the labor force ages 25 and older remains nearly 2 million below its level in the same quarter of 2019.

The pandemic is associated with an increase in some gender disparities in the labor market. Among adults 25 and older who have no education beyond high school, more women have left the labor force than men. Other disparities have stayed the same or even narrowed: The gender pay gap has remained steady, for example, and the difference in the average hours worked by men and women has slightly diminished.

The COVID-19 recession differed from prior recent recessions in that it disproportionately eliminated jobs employing women. Media accounts often referred to it as a “shecession.” As the economy and labor market have been recovering for more than 21 months, Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to investigate if there are lingering impacts on the labor market opportunities of women.

Labor force estimates and average hours worked are derived from the monthly Current Population Survey (CPS), sponsored jointly by the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The CPS is the nation’s premier labor force survey and is the basis for the monthly national unemployment rate released on the first Friday of each month. The CPS is based on a sample survey of about 70,000 households. The estimates are not seasonally adjusted.

For a quarter of the sample each month, the CPS also records data on usual hourly earnings for workers paid by the hour and usual weekly earnings and hours worked for other workers.

The CPS microdata files analyzed were provided by the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) at the University of Minnesota.

The COVID-19 outbreak has affected data collection efforts by the U.S. government in its surveys, especially limiting in-person data collection. This resulted in about an 8 percentage point decrease in the response rate for the CPS in September 2021. It is possible that some measures of labor market activity and its demographic composition are affected by these changes in data collection.

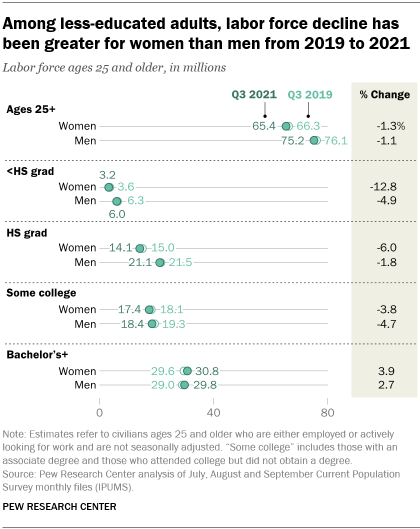

Overall, the number of women ages 25 and older in the labor force has fallen 1.3% since the third quarter of 2019, similar to the 1.1% decline of men in the labor force.

But this modest overall change obscures divergent outcomes for labor force members with different levels of education. Women who have no education beyond high school exited the labor force in greater numbers than similarly educated men. However, the pandemic has not interrupted the long-running gains of women among the college-educated labor force.

From the third quarter of 2019 to the same quarter of 2021, the number of women in the labor force who are not high school graduates decreased 12.8%, dwarfing the 4.9% contraction among comparably educated men. The pandemic also disproportionately affected women with a high school diploma. The ranks of women in the high-school-educated labor force have declined 6.0% since the third quarter of 2019. The labor force of similarly educated men has fallen only 1.8%.

Among the labor force with at least some amount of education beyond high school, women have fared at least as well as men. The number of men and women in the labor force who have some college experience but not a bachelor’s degree has contracted for both groups, with no strong disparities between the two. Both men and women with at least a bachelor’s degree saw positive gains in the labor force (2.7% and 3.9%, respectively) from 2019 to 2021.

What accounts for the larger labor force withdrawals among less-educated women than men during the pandemic? It is complex but there seems to be a consensus that it partly reflects how women are overrepresented in certain health care, food preparation and personal service occupations that were sharply curtailed at the start of the pandemic. Although women overall are more likely than men to be able to work remotely, they are disproportionately employed in occupations that require them to work on-site and in close proximity to others.

It is less clear whether women’s parental roles and limited child care and schooling options have played a large role in forcing them to exit the labor market. The number of mothers and fathers in the labor force has declined in similar fashion over the past two years.

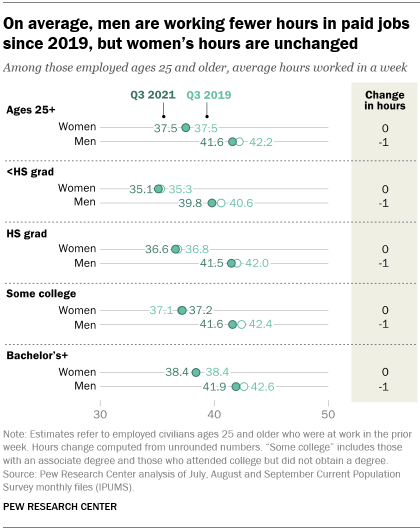

Turning to the number of hours employees work per week, on average, there have been small changes associated with the pandemic and they have occurred among men. In the third quarter of 2021, women ages 25 and older worked 37.5 hours on average in paid employment, unchanged from how much they worked two years earlier. Men ages 25 and older worked 41.6 hours on average in the third quarter of 2021. That is 0.7 fewer hours than they worked pre-pandemic (42.2). So, the disparity in hours of paid employment between women and men workers has somewhat narrowed.

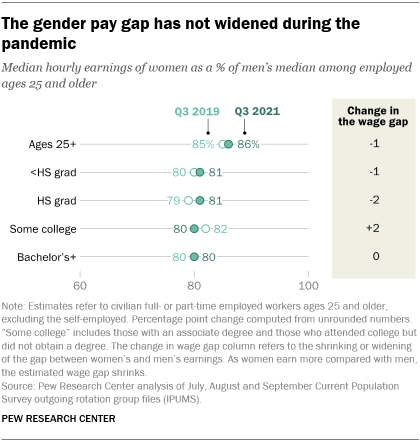

The pandemic is also not associated with a widening of the gender pay gap. Among full- and part-time workers ages 25 and older, women earned 86% of what men earned based on median hourly earnings in the third quarter of 2021. Two years ago, the estimated gender pay gap was 85%.

The overall pay gap partly reflects that employed women have higher levels of education than employed men. In 2021, 48% of women workers ages 25 and older had completed at least a bachelor’s degree compared with 40% of men. Workers with at least a bachelor’s degree tend to earn more and thus women’s earnings are boosted by their greater educational attainment. The gender pay gap is greater when you look at groups of women and men with equal levels of education. The gap depends on the education level, but in 2021 women ages 25 and older earned closer to 80 cents on the dollar compared with equally educated men.