In many ways, Black people in the United States are more religious than Americans of other races. This is especially true for immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa, who tend to be more religious than U.S.-born Black adults or immigrants from the Caribbean, according to a Pew Research Center survey.

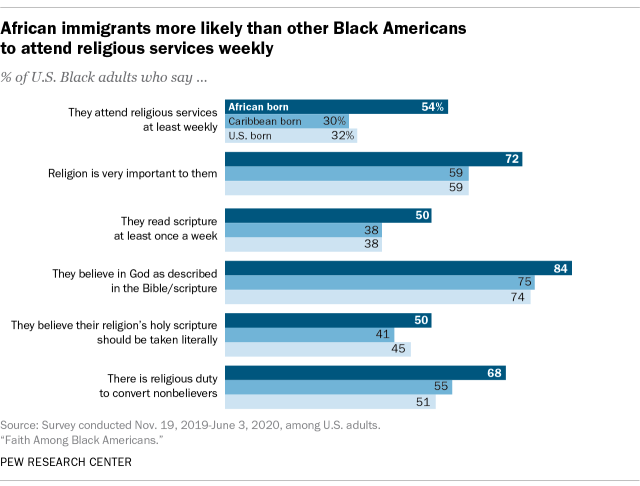

For example, around half of African immigrants in the U.S. (54%) say they attend religious services at least weekly, compared with about three-in-ten U.S.-born (32%) and Caribbean-born (30%) Black adults. And about seven-in-ten African immigrants (72%) say religion is very important to them, compared with 59% of U.S.- and Caribbean-born Black adults who say this.

This post examining the religious affiliations, practices and beliefs of Black immigrants in the United States draws from Pew Research Center’s landmark study, “Faith Among Black Americans,” published in February 2021. That study was based on a nationally representative survey of 8,660 Black adults (ages 18 and older) who identify as Black or African American, including some who identify as both Black and Hispanic or Black and another race (such as Black and White, or Black and Asian).

Survey respondents were recruited from four nationally representative sources: the Center’s American Trends Panel (conducted online), NORC’s AmeriSpeak panel (conducted online or by phone), Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel (conducted online) and a national cross-sectional survey by Pew Research Center (conducted online and by mail). Responses were collected from Nov. 19, 2019, to June 3, 2020, but most respondents completed the survey between Jan. 21 and Feb. 10, 2020.

Here are the questions used for the “Faith Among Black Americans” report, along with responses, and its methodology.

Statistics in the post about the number of Black immigrants in the U.S. come from a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data.

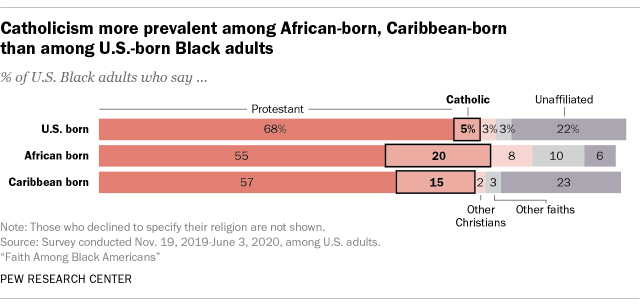

In addition, immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa are much less likely than other U.S. Black adults to be religiously unaffiliated (that is, to identify as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”). Just 6% of African immigrants identify in one of these ways, compared with 22% of U.S.-born Black adults and 23% of Black immigrants from the Caribbean.

The religious profiles of immigrant groups differ in other ways, too. Both African and Caribbean immigrants are somewhat less likely to be Protestant, and more likely to be Catholic, than U.S.-born Black adults. And African immigrants are more likely than other Black Americans to identify with other Christian faiths such as Orthodox Christianity, or with non-Christian faiths such as Islam.

While the vast majority of the 47 million Black Americans were born in the U.S., the Black immigrant population has roughly doubled over the last two decades to 4.6 million in 2019, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. In 2019, roughly one-in-ten Black Americans were born outside of the U.S., including 4% who were born in sub-Saharan Africa and 5% who were born in the Caribbean. More Black Americans come from Jamaica, Haiti, Nigeria and Ethiopia than from any other African or Caribbean countries, according to Pew Research Center tabulations of the Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey.

Some Black Christian immigrants go to churches associated with historically Black Protestant denominations based in the U.S., such as the Progressive National Baptist Convention, while others go to congregations of Haitian Baptists, Pentecostals and Catholics, or those associated with African denominations such as the Presbyterian Church of Ghana and the Nigeria-based Church of the Lord.

African immigrants also distinguish themselves in the survey through their beliefs about scripture and conversion. Immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa are more likely to say they believe in God as described in their religion’s holy scripture – such as the Bible for Christians or the Quran for Muslims – than are U.S.-born Black adults. About eight-in-ten African immigrants (84%) say they believe this, compared with around three-quarters in the other groups. And roughly seven-in-ten African immigrants (68%) say people of faith have a duty to convert nonbelievers, compared with approximately half of U.S.-born and Caribbean-born adults who feel this way.

African immigrants also stand out on certain social and cultural issues. Fewer than half of African-born Americans (38%) say homosexuality should be accepted by society, compared with 63% of U.S.-born Black adults. Caribbean-born immigrants fall between the other two groups, with roughly half (52%) saying that homosexuality should be accepted by society. (In general, opposition to homosexuality is far more common in sub-Saharan Africa than it is in the U.S.)

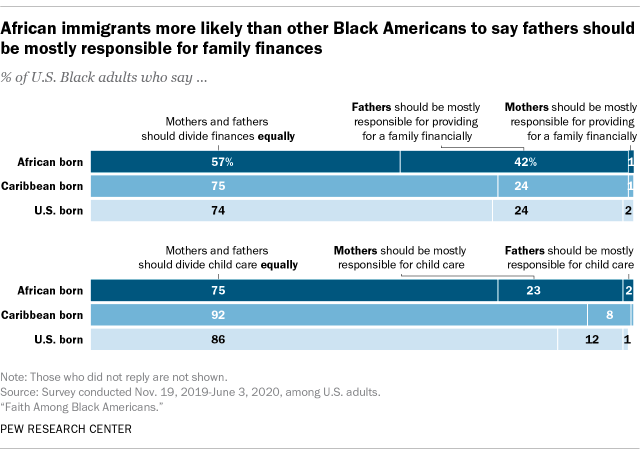

And African immigrants tend to be more supportive of traditional gender norms, in some ways, than U.S.-born Black adults. For example, those born in sub-Saharan Africa differ from other Black Americans on questions about how men and women should share duties in households that have both a mother and father. African immigrants are more likely than other Black adults to say the father should be mostly responsible for providing for the family financially, and that the mother should be mostly responsible for taking care of the children. However, the most common view in all groups is that both parents should divide these responsibilities equally.