More than 40 million people in the United States have a disability, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. But even as majorities of these Americans report having certain technologies, the digital divide between those who have a disability and those who do not remains for some devices.

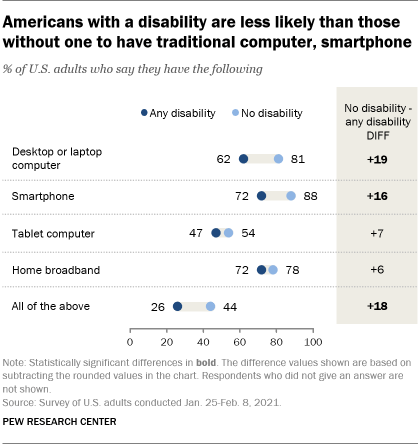

Some 62% of adults with a disability say they own a desktop or laptop computer, compared with 81% of those without a disability, according to a Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults conducted Jan. 25-Feb. 8, 2021. And when it comes to smartphone ownership, there is a gap of 16 percentage points between those with a disability and those without one (72% vs. 88%).

Despite these gaps, similar shares of Americans – regardless of disability status – say they have broadband at home or a tablet computer. For example, 72% of adults with a disability report having high-speed internet at home, a figure that does not differ statistically from the 78% of adults without a disability who say the same. And there is no statistically significant difference in tablet ownership between adults who report having a disability (47%) and those who do not have a disability (54%).

Pew Research Center has studied Americans’ internet and technology adoption for decades. For this analysis, we surveyed 1,502 U.S. adults from Jan. 25 to Feb. 8, 2021, by cellphone and landline phone. The survey was conducted by interviewers under the direction of Abt Associates and is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, education and other categories. Here are the questions, responses and methodology used for this analysis.

Due to the nature of the live telephone surveys, some Americans with disabilities are likely underrepresented in this analysis. The figures reported on adoption and internet use are from a phone survey that was conducted via landlines and cellphones and likely under-covered adults who are deaf or have difficulty speaking. In addition, our surveys do not cover those living in institutionalized group quarters, which may include some individuals who are severely disabled.

There is, however, variation by disability status when considering ownership of all these devices that enable people to go online. Roughly a quarter of Americans with disabilities (26%) say they have high-speed internet at home, a smartphone, a desktop or laptop computer and a tablet, compared with 44% of those who report not having a disability.

Whether or not someone goes online also varies by disability status. Americans with disabilities are three times as likely as those without a disability to say they never go online (15% vs. 5%). And while three-quarters of Americans with disabilities report using the internet on a daily basis, this share rises to 87% among those who do not have a disability.

Overall, roughly one-in-five U.S. adults (18%) report that they have a disability, according to this survey, which asked respondents if any “disability, handicap, or chronic disease keeps you from participating fully in work, school, housework, or other activities, or not.” (It is important to note that there are various forms of disabilities, often differing in severity, and a range of ways to measure disability in public opinion surveys.)

Older Americans are more likely than younger adults to report having a disability. At the same time, these older age groups generally have lower levels of digital adoption than the nation as a whole.

There are tools on the market aimed at making the digital experience more accessible to Americans with disabilities. For example, a new search engine is in the works to help those with disabilities find websites that are accessible to them. And social media companies have experimented with artificial intelligence to help the visually impaired use their platforms, while other companies are expanding their screen-reading software and mobile apps. At the same time, there have been many lawsuits over the years claiming some websites are not accessible to those with disabilities.

Note: Here are the questions, responses and methodology used for this analysis. This is an update of a post by Monica Anderson and Andrew Perrin originally published April 7, 2017.

Read the other posts in our digital divide series: