Sometimes the work patterns of Congress resemble those of a grumpy teenager heading back to school after summer vacation: It can take a while to shake off the cobwebs, buckle down and get to the tasks of setting budgets, holding hearings and passing bills. And, as we’ve noted before, some of the heaviest legislative lifting gets done late in each session.

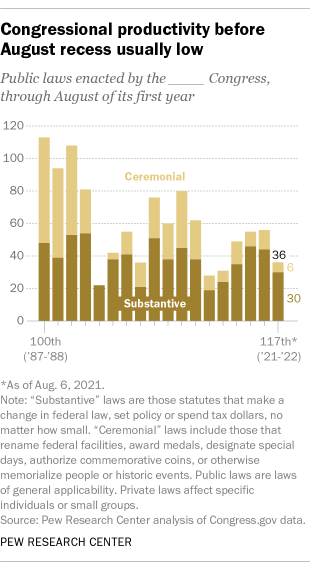

So, it shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that, as of this writing, the 117th Congress’ total legislative output stands at 36 laws – only 30 of which count, by our deliberately generous criteria, as substantive legislation. (This analysis defines substantive laws as those that changed written law, spent money or established policy, no matter how minor.)

This post is the latest in a series, starting in 2014, examining the productivity of Congress. Legislative productivity can be measured in many different ways – by counting the number of pages in the statute book, how many votes were taken, comparing bills introduced with bills enacted, and so on.

We’ve chosen a fairly straightforward approach: how many laws (public laws in most cases, as opposed to private laws that apply to single individuals) each Congress actually enacts. We also distinguish between substantive and ceremonial laws. In general, substantive laws are those that have some real-world impact, no matter how small – be it spending federal dollars, setting policy, adjusting the boundaries of a national park or merely correcting a typographical error in an earlier law that was needed make its meaning clear.

Ceremonial laws are those intended primarily to honor or recognize an individual, group or cause – for example, naming or renaming post offices, courthouses and other federal facilities, authorizing commemorative coins or congressional gold medals, or authorizing outside groups to erect memorials on federal land. For each Congress, we reviewed the text of each law passed to sort it into the appropriate category.

We relied on Congress.gov, an online repository of legislative data and information maintained by the Library of Congress, as our source for laws that were enacted. The analysis was confined to the first eight months or so of each congress – that is, from Jan. 3 through the end of August – in order to capture only those laws passed before the annual summer recess, which typically begins in early August and often runs well past Labor Day.

In most cases we refer to each Congress using the two calendar years that make up the bulk of the time each Congress is in session, though a Congress formally ends in the subsequent odd-numbered year. (For example, the 116th Congress of 2019-20 concluded on Jan. 3, 2021.)

That puts the 117th Congress in a tie for the fourth fewest laws enacted in the first eight months of its two-year term – and fifth fewest in terms of substantive laws – among the 18 most recent Congresses, going back to 1987.

Like high schoolers, Congress takes a long summer break. Lawmakers typically adjourn in early August, which makes this is a good opportunity to check in on their legislative productivity. The Senate broke earlier this week after passing its version of President Joe Biden’s big infrastructure package; it won’t be back till Sept. 13. The House adjourned on July 30 and isn’t scheduled to return till Sept. 20; however, Majority Leader Steny Hoyer has said House members might be summoned back early to vote on the infrastructure deal.

The low totals don’t mean the 117th has done nothing of significance. The biggest piece of legislation so far has been the American Rescue Plan Act, the $1.9 trillion economic stimulus measure passed in March on nearly party-line votes. Congress also extended the Paycheck Protection Program, made Juneteenth a federal holiday, and appropriated $1.9 billion to wind down the war in Afghanistan, resettle Afghans who aided U.S. forces there, and respond to the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol.

However, much potentially major legislation appears to be stymied, at least for now. Among the pending or tabled items: the For the People Act, a massive election reform bill; an increase in the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $15 an hour; an extension of the nationwide eviction moratorium to bolster the more limited one issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the creation of an independent commission to investigate the Jan. 6 attack (although House Speaker Nancy Pelosi pushed ahead with creating a House select committee after Republicans balked on it).

Three of the laws we deemed as “substantive” are actually repeals of agency rules issued during the Trump administration. The Congressional Review Act gives Congress the ability to undo newly issued rules within a specified time period, something that becomes especially relevant after an election that changes party control of the White House. In 2017, for instance, 14 of the 46 laws passed by the new GOP-controlled Congress and signed by President Donald Trump overturned rules issued in the waning days of the Obama administration.

Of the 18 Congresses we examined, the lowest in terms of overall legislative output – including both substantive and ceremonial measures – in its first eight months was the 104th (1995-96). The 104th was the first in more than four decades to have Republicans running both chambers, and it was at loggerheads with Democratic President Bill Clinton almost from the moment its term began. By mid-August 1995, only 22 measures had become law.

By contrast, the 100th Congress had churned out 113 new laws by the time it went on its summer vacation in August 1987. However, well over half (65) of those laws were ceremonial in nature – mostly designating special “observances” such as National Know Your Cholesterol Week (April 5-11) and National Catfish Day (April 4). Those sorts of commemorations were almost entirely eliminated in the mid-1990s.

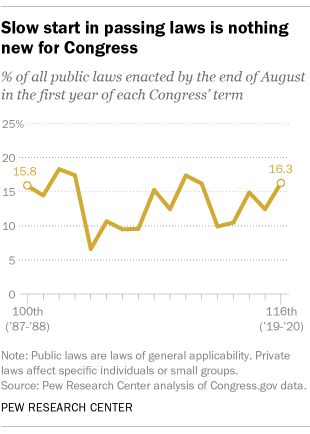

Getting off to a slow start doesn’t necessarily make for an unproductive Congress. On average, the 100th through 116th Congresses had passed about 13.4% of their entire legislative output by their first August recess – a rate that, in most cases, varies by a few percentage points in either direction from one Congress to the next.