As businesses across the United States return to near-normal operations, public attention has shifted to reports of labor shortages and rising prices. But even as hiring picks up in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak, the labor market is not fully healed. Some 9.5 million U.S. workers were unemployed in June 2021, compared with 5.7 million in February 2020, and the unemployment rate stood at 5.9%, up from 3.5%, seasonally adjusted.

Immigrants were hit harder than U.S.-born workers at the beginning of the pandemic, but they have since closed the gap, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of government data. There were 27.3 million foreign-born workers in the U.S. in 2020, accounting for 17.0% of the total labor force. They entered the pandemic on the same footing as U.S.-born workers but saw their unemployment rate increase more sharply with the onset of the COVID-19 recession. A year later, with the economic recovery gaining momentum, unemployment among immigrants is about equal with that of U.S.-born workers. However, for both groups, the unemployment rate remains greater than the pre-pandemic level.

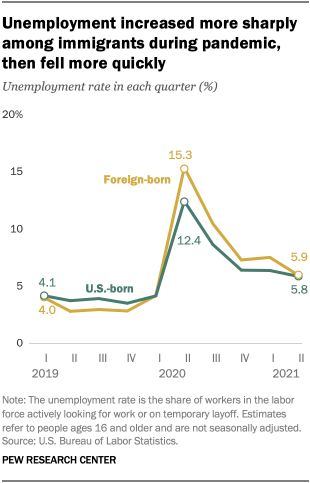

In the first quarter of 2019, immigrant and U.S.-born workers each had an unemployment rate of about 4.0%. It dipped below that level for much of 2019 for both groups, but more so for immigrants. By the first quarter of 2020, the unemployment rate for foreign-born workers (4.1%) was back on par with that of U.S.-born workers, not seasonally adjusted.

To understand how the economic downturn brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic impacted immigrant workers in the United States, Pew Research Center analyzed data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and from the 2019, 2020 and 2021 Current Population Survey monthly files (IPUMS-CPS).

The CPS is the U.S. government’s official source for monthly estimates of unemployment. In this report, monthly CPS files were combined to create quarterly files so as to boost sample sizes and to dampen the effects of month-to-month seasonal variations in the estimates. The statistical significance of differences between estimates are based on 90% confidence intervals.

The COVID-19 outbreak has affected data collection efforts by the U.S. government in its surveys, limiting in-person data collection and affecting the response rate. It is possible that some measures of labor market activity and how they vary across demographic groups are affected by these changes in data collection.

The onset of the pandemic sent the unemployment rate for immigrants soaring higher than the rate for U.S.-born workers. By the second quarter of 2020, the unemployment rate for foreign-born workers had reached 15.3%, compared with 12.4% for U.S.-born workers. Unemployment among both groups decreased as the economy began to recover, but more so among immigrants. By the second quarter of 2021, the unemployment rate for immigrants (5.9%) was back at parity with the unemployment rate for U.S.-born workers (5.8%).

The unemployment rate for foreign-born workers also increased more than the rate for U.S.-born workers in the Great Recession, although not to the extent seen in 2020. Immigrants tend to be more vulnerable in recessions because they are less likely to have attended college and many are unauthorized. Among men, immigrants are also more likely than U.S.-born workers to hold jobs in construction, an industry that was vulnerable in the housing market crash that accompanied the Great Recession. Among women, immigrants are relatively more likely to work in the leisure and hospitality and other services sectors – also a liability in the pandemic as social distancing rules had a severe impact on those businesses.

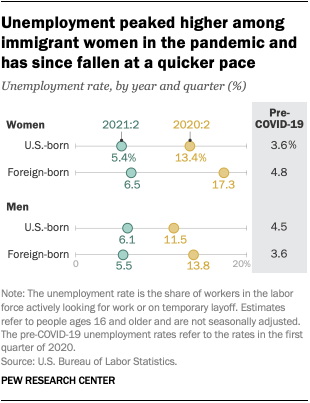

The pandemic-driven volatility in unemployment was most notable among immigrant women. Prior to the pandemic, the unemployment rate for foreign-born women (4.8%) was slightly higher than the 3.6% rate for U.S.-born women. As the recession hit, the unemployment rate for foreign-born women jumped to 17.3% in the second quarter of 2020, a greater increase than was experienced by U.S.-born women, whose rate peaked at 13.4%. The recovery has proceeded at a faster pace for immigrant women, however. As of the second quarter of 2021, the unemployment rate for immigrant women (6.5%) was greater than the rate for U.S.-born women (5.4%), but the gap was no greater than in the pre-COVID-19 period.

Foreign-born men also saw a sharper increase in unemployment than U.S.-born men at the beginning of the pandemic. From the first to the second quarter of 2020, the unemployment rate for foreign-born men increased from 3.6% to 13.8%. This was greater than the increase experienced by U.S.-born men, whose unemployment rate went up from 4.5% to 11.5%. By the second quarter of 2021, the unemployment rate for immigrant men (5.5%) had dropped below the rate for U.S.-born men (6.1%), restoring the status quo from before the pandemic.

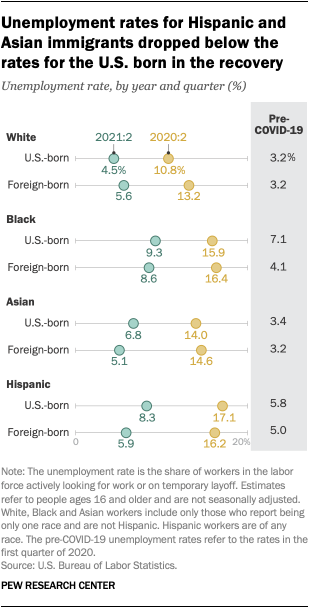

Hispanic and Asian immigrants, who collectively account for nearly three-in-four foreign-born workers in the U.S., initially saw their unemployment rates increase in tandem with the rates for U.S.-born Hispanic and Asian workers. Among Hispanic workers, the unemployment rate for immigrants increased from 5.0% pre-COVID-19 to 16.2% in the second quarter of 2020. U.S.-born Hispanic workers saw their unemployment rate rise from 5.8% to 17.1%. Similarly, the unemployment rate among immigrant and U.S.-born Asian workers increased by about 11 percentage points each with the onset of the pandemic.

But the economic recovery has opened a wider gap in the unemployment rate in favor of Hispanic and Asian immigrants. Among Asian workers, immigrants had a lower unemployment rate (5.1%) than the U.S. born (6.8%) in the second quarter of 2021, compared with a state of parity prior to the pandemic. Among Hispanic workers, the unemployment rate for immigrants (5.9%) in the second quarter of 2021 was further below the rate for U.S.-born Hispanic workers (8.3%) than where it stood prior to the pandemic.

In contrast, White and Black immigrants have lost ground to U.S.-born White and Black workers over the course of the pandemic. Among White workers, immigrants and the U.S. born had the same unemployment rate prior to the pandemic. But, as of the second quarter of 2021, the unemployment rate among White immigrants (5.6%) stood above the rate for U.S.-born White workers (4.5%).

Among Black workers, the unemployment rate for immigrants (4.1%) was notably lower than the rate for the U.S. born (7.1%) prior to the pandemic. This edge had dissipated by the second quarter of 2021, with U.S.-born and immigrant Black workers experiencing an unemployment rate of about 9% each.

Wages fluctuated greatly along with unemployment

Job losses in the COVID-19 recession were particularly severe in sectors in which social distancing of workers is difficult. The leisure and hospitality sector alone accounted for more than a third of all nonfarm jobs lost from the first to the second quarter of 2020, shedding 38% of its workforce in that period, according to government data. Many of these workers were at the lower end of the wage scale.

As the pandemic struck, the economy-wide median hourly wage increased sharply from 2019 to 2020, reflecting the fact that higher-wage workers were more likely to have held on to their jobs. Among immigrants, the median wage increased from $18.61 in the second quarter of 2019 to $21.03 in the second quarter of 2020, an increase of 13.0%. U.S.-born workers registered a similar increase, as their median wage increased by 12.5%, from $20.29 to $22.83. (All wages are expressed in 2021 second-quarter dollars.)

The restoration of jobs generally, and particularly so in the leisure and hospitality and other services sectors, has at least partly pushed the median wage down since the initial shock of the pandemic. For immigrants, the median wage has fallen 4.9% from the second quarter of 2020 to the second quarter of 2021. The median wage of U.S.-born workers has fallen 5.8% in the same period. But for both groups of workers, wages have increased substantially from 2019 to 2021 – a comparison less affected by large swings in unemployment, albeit not entirely so.

Immigrant women, who experienced the sharpest rise in unemployment in the pandemic, also appeared to see the sharpest increase (19.6%) in the median wage from 2019 to 2020. Since then, their median wage has fallen by about the same measure as among U.S.-born women and both immigrant and U.S.-born men. Overall, the longer-term impact of the pandemic on the earnings of workers may not be clear until the labor market has healed more fully, with employment and labor force participation back to near pre-pandemic levels.