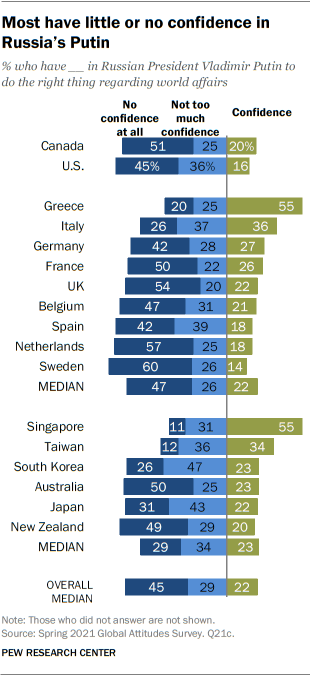

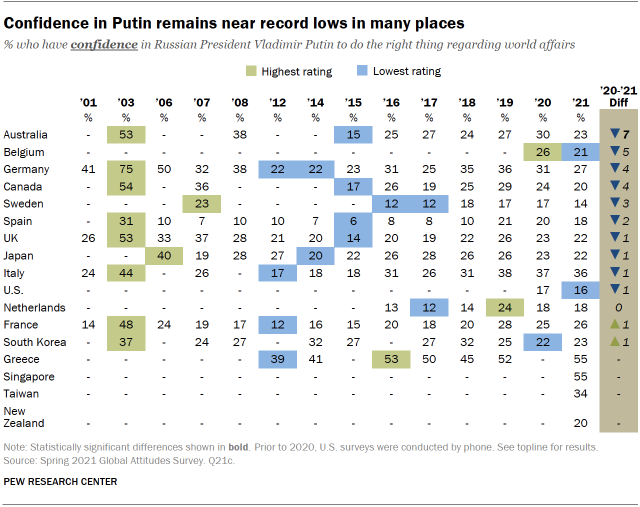

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s global image has been consistently low for years in many countries, and a Pew Research Center survey conducted this spring in 17 advanced economies shows that negative views of him are at or near historic highs in most places. Today, a median of 22% say they have confidence in Putin to do the right thing in world affairs, compared with a median of 74% who say they have no such confidence.

Singapore (55%), Greece (55%), Italy (36%) and Taiwan (34%) stand out as the only places surveyed where roughly a third or more say they have confidence in the Russian president. Confidence is lowest in Sweden (14%) and the United States (16%). In both of these countries, as well as in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, France, New Zealand and Belgium, at least 45% or more say they have no confidence at all in him.

While confidence in Putin has been quite low in many countries for much of the last decade –particularly following the annexation of Crimea in 2014 – it has dropped even further in the past year in Australia (down 7 percentage points).

This analysis focuses on public attitudes toward Russian President Vladimir Putin in 17 advanced economies in North America, Europe and the Asia-Pacific. For non-U.S. data, the report draws on nationally representative Pew Research Center surveys of 16,254 adults from March 12 to May 26, 2021, in 16 advanced economies. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the UK, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan.

In the United States, we surveyed 2,596 U.S. adults from Feb. 1 to 7, 2021. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories.

This study was conducted in places where nationally representative telephone or web surveys are feasible. Due to the coronavirus outbreak, face-to-face interviewing is not currently possible in many parts of the world.

Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses. See our methodology database for more information about the survey methods outside the U.S. For respondents in the U.S., read more about the ATP’s methodology. Information on populist party categorization can be found here.

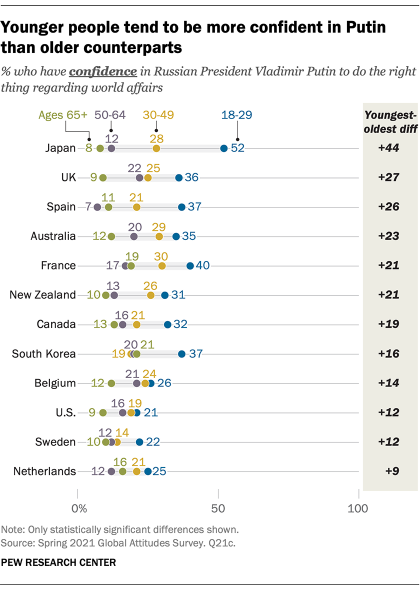

Across many places surveyed, younger people have more confidence in Putin than their older counterparts. The largest difference by far is in Japan (44 percentage points between the youngest and oldest respondents) though there are differences of at least 20 points in the UK, Spain, Australia, France and New Zealand. Though the difference is smaller in the U.S., Americans under 30 are also more likely to have confidence in Putin, with roughly a fifth of 18- to 29-year-olds saying so, compared with only 9% of those 65 and older.

These age-related patterns have often been prevalent in views of Putin. And when it comes to opinion about Russia more generally, younger adults also tend to have more favorable views of the country than older people.

In some countries, men are more confident in Putin than women. For example, in Germany, 36% of men say they have confidence in Putin to do the right thing in world affairs, while just 19% of women agree. Double-digit differences are also present in France, Italy and Belgium, while gender differences are smaller in Canada, Spain and New Zealand. Those with less education also have more confidence in Putin than those with more education in about half the countries surveyed. In Italy, for example, roughly a quarter of those with a postsecondary degree or higher have confidence in Putin, while nearly four-in-ten of those with no postsecondary degree have confidence in him. Similar differences persist across eight other countries polled.

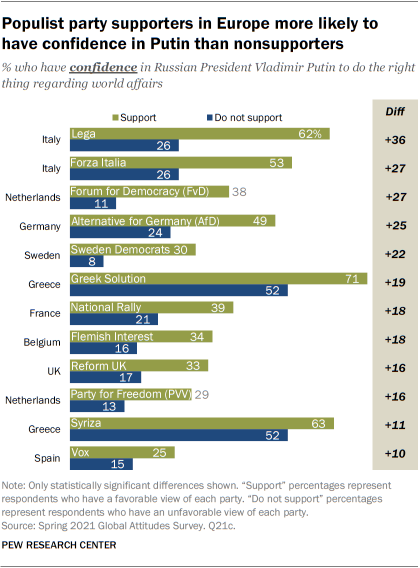

In Europe, supporters of populist parties, both right- and left-wing, are more likely to have confidence in Putin than those who don’t support such parties. For example, in Italy, those with a favorable view of right-wing Lega are more than twice as likely to have confidence in Putin as those with an unfavorable view (62% vs. 26%, respectively). The same goes for supporters of Forza Italia – roughly half have confidence in Putin to do the right thing, while roughly a quarter of nonsupporters say the same.

In the U.S., Republicans and Republican-leaning independents tend to have more confidence in Putin than Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (20% vs. 12%, respectively). Still, overwhelming majorities in both parties lack confidence in Putin.

More broadly, in some countries people who identify themselves as ideologically right-leaning are more likely than those on the left to have confidence in Putin. The largest such difference is, again, in Italy, where a majority (56%) of those on the right say they have confidence in Putin while just 19% on the left agree. In Sweden, Greece, France, Canada, Germany, Australia, the UK and the U.S., there are also double-digit differences between the right and left.

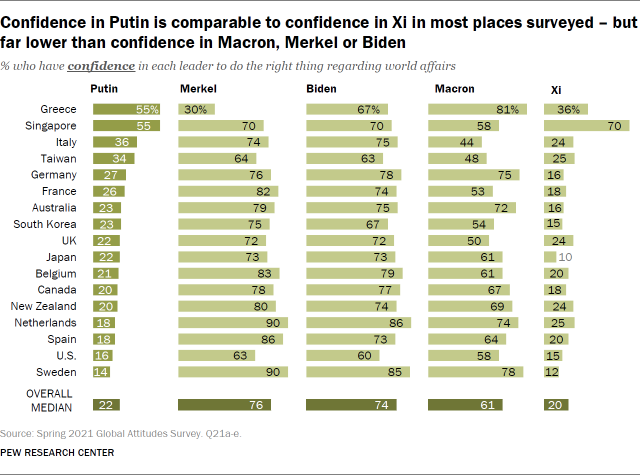

When it comes to comparisons with other global leaders, confidence in Putin is substantially below that in German Chancellor Angela Merkel, U.S. President Joe Biden and French President Emmanuel Macron. Yet his ratings are quite comparable – and slightly better in some of the European countries surveyed – to Chinese President Xi Jinping’s.

Confidence in Xi and confidence in Putin are closely related: Places with higher levels of confidence in one tend to also have higher levels of confidence in the other. The opposite is true of Merkel – places with higher levels of confidence in Merkel tend to have less confidence in Putin.

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses. See our methodology database for more information about the survey methods outside the U.S. For respondents in the U.S., read more about the ATP’s methodology. Information on populist party categorization can be found here.