Most Americans favor raising the federal minimum wage, which has been $7.25 an hour since 2009. About six-in-ten adults (62%), including majorities in nearly every demographic group, support increasing the minimum wage to $15 an hour. Even among the 38% of Americans who oppose a $15 minimum, most say they’d support a smaller increase, according to an April Pew Research Center survey.

But popular support doesn’t necessarily translate into government action. Proposals to raise the federal minimum wage have stalled out repeatedly in Congress over the past decade. While the Center surveyed the general public rather than lawmakers, the findings suggest that partisan divisions among legislators reflect those of Americans as a whole. More than seven-in-ten Republicans and GOP-leaning independents (72%) oppose raising the wage to $15 an hour, including 45% who strongly oppose it, while 87% of Democrats and Democratic leaners say they favor such an increase (including 61% who strongly favor it).

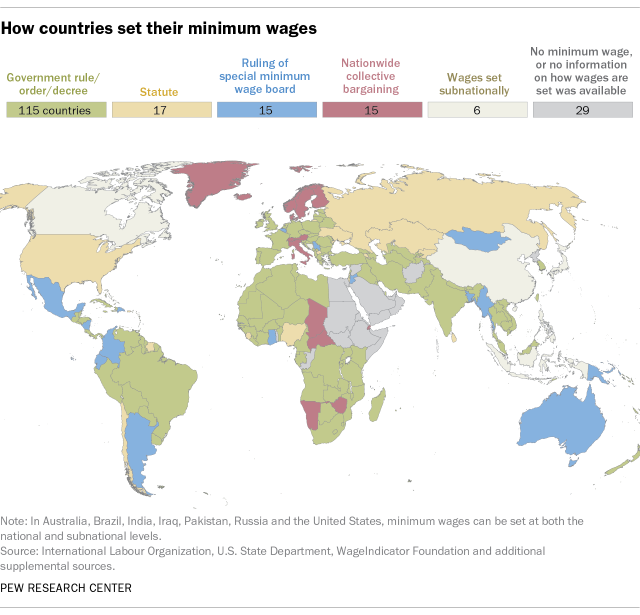

Such sharp partisan divides matter because the federal minimum wage is set out in statute (the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, to be specific), meaning it can only be changed if Congress passes a bill to do so and the president signs it (or Congress overrides his veto). Putting minimum wage policy directly in the hands of lawmakers is just one of several ways in which the U.S. approach stands apart from most other countries.

Given the renewed prominence of the federal minimum wage in U.S. politics, this post looks at how other nations around the world address this perennially contentious issue.

We chose as our universe the United Nations’ 193 member nations and two non-member observer states (Palestine and Vatican City), plus two self-governing non-members (Kosovo and Taiwan), for a total of 197 countries and territories.

Because there’s no single authoritative source of information on the minimum-wage systems of every country, we drew on multiple sources for this analysis. The most important were the International Labour Organization, particularly its Working Conditions Laws Database and its “Global Wage Report 2020-21”; the U.S. State Department’s annual “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices”; and the WageIndicator Foundation, a Netherlands-based nongovernmental organization that promotes labor market transparency and gathers data on, among other things, minimum-wage rates and rules for most countries.

When necessary, we supplemented those sources with information from media reports, academic studies, government websites and consultants’ reports, among others.

For purposes of this analysis, we considered a country to have a “generally applicable minimum wage system” if it covers all or most private-sector adult workers. Systems that only apply to the public sector were excluded because in essence the government is simply setting a pay scale for its own workers.

In some Middle Eastern countries, foreign workers constitute the majority of the private-sector labor force; in such cases, minimum wage laws that applied only to native-born workers weren’t deemed “generally applicable.”

Finally, bear in mind that minimum wages generally apply only to workers in the formal economy. In some countries that we classify as having generally applicable minimums, significant shares of the workforce work in the “informal economy” and thus aren’t covered.

We examined 197 countries and self-governing territories to see how (and whether) they set and adjust minimum wages, and to get a sense of just how much of an outlier the United States is in this area. We identified 173 with some sort of generally applicable minimum-wage system, defined as one that covers all or most of a country’s adult private-sector workers.

Here’s what we found:

The U.S. is one of a handful of countries where the legislature has primary responsibility for setting minimum wages.

Only 17 countries (about 10% of those with minimum-wage systems) set their rates by statute, which (as U.S. experience demonstrates) can make them more difficult to update.

In at least 115 countries, the central government (or an official such as a labor minister) sets minimum wages by regulation, order or decree, typically pursuant to some authorizing law. In about three-quarters of those countries, government action is supposed to come only after input from workers’ and employers’ organizations – ranging from unspecified “consultations” to formal recommendations from structured minimum wage boards or commissions. (The International Labour Organization’s 1970 Minimum Wage Fixing Convention, which 54 nations have ratified, calls for such dialogue, which may help explain its prevalence.)

Minimum wage commissions typically include representatives of workers and employers, often joined by government officials (in which case they’re called “tripartite”), and sometimes independent economic experts or representatives of civil society (“tripartite-plus”). In at least 15 countries, such bodies are themselves authorized to set minimum wages, if they can come to consensus on them.

Fifteen countries – 10 European and five African – rely on collective bargaining between unions and employers’ organizations to set wage levels, including minimum wages. Such negotiations typically take place at the sector or industry level, and the resulting agreements generally have the force of law.

Unlike many countries, the U.S. has no legal requirement to periodically review and, if necessary, adjust its minimum wage.

At least 80 countries where minimum wages are set either by or pursuant to national law have an explicit requirement to revisit them every so often – in most cases annually or once every two years.

Fifty countries have no explicit requirement for periodic review, and in 22 cases we couldn’t find any definite information either way. Even so, indications are that most countries revisit their minimum wages more frequently than the U.S. does: Between 2010 and 2019, according to a 2020 International Labour Organization report, 134 countries adjusted their minimum wages no less frequently than every three to five years.

In the U.S. – unlike in most countries – states, counties and cities can set their own minimum wage rates.

In the great majority of countries – 145, by our reckoning – minimum wages are the exclusive domain of the national government, a national minimum wage board or some other central authority. The U.S. is one of only seven countries where states, provinces, cities or other subnational governments have concurrent authority to set their own minimum wages (so long as they’re not below the national minimum). In six countries, minimum wages are the exclusive responsibility of subnational entities.

Generally speaking, the countries that do give subnational units minimum-wage authority are large and complex (China, India, Indonesia), have long traditions of decentralized power (Canada, Australia), and/or have strong regional identities (Iraq, Bosnia and Herzegovina).

Nearly half (83, or 48%) of all countries with minimum wage systems have a single, broadly applicable national minimum. We don’t count the U.S. in this group because the $7.25 federal minimum wage is actually used in just 21 of the 50 states, which together account for about 40% of U.S. wage and salary workers. The other 29 states, as well as the District of Columbia and several cities and counties, have higher minimums. (The highest local minimum wage, $16.84 an hour, is in Emeryville, Calif.)

India was supposed to get its first nationwide floor wage in 2020, but the government deferred it indefinitely due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

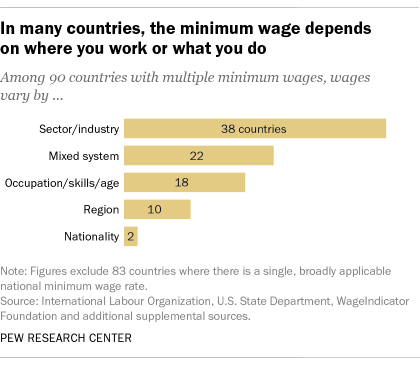

Ninety other countries have at least two and up to several dozen minimum wages, which can vary by region, industry, occupation, experience or a combination of those factors. For instance, Panama, a country of about 4.2 million people, has minimum wage scales in 20 different sectors. Within each sector, minimums vary by region (there are two) and by type of business within each region. (Public-sector workers, interestingly, are exempt from minimum wage rules, and generally earn less than their private-sector counterparts.)

One thing rapidly became clear from our review: No two countries have exactly the same minimum wage systems, and many have combinations of features that defy easy categorization. A few examples:

- In Austria, at the behest of the federal government, workers’ and employers’ organizations in 2017 negotiated a national minimum wage of 1,500 euros a month that applies across all sectors. This wage floor was implemented not by a national law, but sector by sector via the collective bargaining agreements that historically set the nation’s wage policies.

- In Switzerland, minimum wages are set through industrywide collective agreements, which cover about 40% of the workforce. But a federal “standard employment contract” sets the minimum wage for domestic workers, and four of 26 cantons have their own general minimum wages.

- Saudi Arabia’s “minimum wage” of 4,000 riyals a month (about $1,067) is tied to the government’s “Saudization” program to increase private-sector employment of Saudi nationals. Businesses must employ a certain number (varying by industry and size) of Saudi nationals, and only Saudis making the minimum wage are counted fully toward that quota. However, the minimum wage does not apply to foreign workers, who make up the great majority of the country’s private-sector workforce.

On the other hand, 21 countries have no generally applicable minimum wage at all, though some have set minimums for specific occupations or industries. In five countries that have national minimum wage systems, we could find no reliable information on how they function. Finally, there were three countries (North Korea, Syria and Vatican City) for which we could find no reliable, current information on their minimum wage systems, or indeed if any even exist.