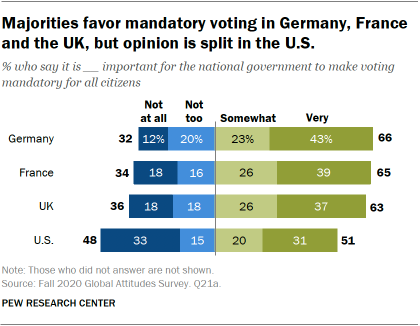

Around two-thirds of adults in Germany, France and the United Kingdom say it is important for their national government to make voting compulsory for all citizens. But views in the United States are much more divided, according to a survey conducted in the four countries in the fall of 2020.

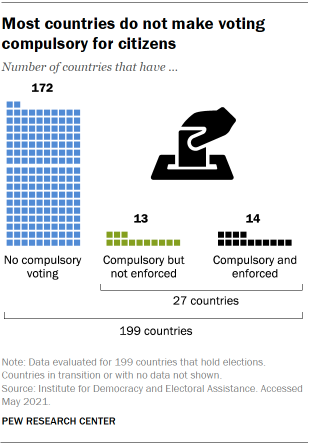

None of the four surveyed countries currently have mandatory voting measures in place, but Germany, France and the UK all require citizens to register to vote. Worldwide, 27 countries have compulsory voting laws, according to the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA).

This analysis examines people’s attitudes toward mandatory voting in France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States, using data from nationally representative telephone surveys of 4,069 adults from Nov. 10 to Dec. 23, 2020, across the four countries. In addition to the survey, we analyzed current laws on compulsory voting around the world, relying on information from the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA).

Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology.

Among the countries surveyed, mandatory voting is most popular in Germany, where 66% of adults say it is important for the national government to require all citizens to vote – including 43% who say it is very important. French adults show similar support for such a policy, with 39% saying it is very important and 26% saying it is somewhat important. In the UK, 63% say it is important for the government to mandate voting for all citizens, including 37% who say it is very important.

In the U.S., where turnout soared in the 2020 presidential election, opinion is about evenly split on the importance of making voting mandatory for all citizens. While 51% say it is important (including 31% who say it is very important), 48% say it is not important, including a third who say it is not at all important for the government to make voting mandatory for all citizens.

There is a stark partisan divide in Americans’ views. Just over a third of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (36%) say it is very or somewhat important for voting to be mandatory for all citizens, compared with a majority of Democrats and Democratic leaners (62%).

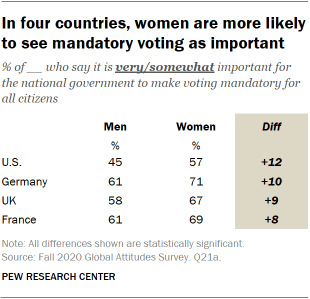

In all four countries surveyed, women are more likely than men to say it is important that the government make voting mandatory for all citizens. For example, 57% of women in the U.S. think such a policy is very or somewhat important, compared with 45% of American men. Similar gender splits occur in Germany (where women are 10 percentage points more likely to say this), the UK (+9 points) and France (+8 points). Women in the U.S. have consistently been more likely than men to vote.

In the U.S., Germany and the UK, those with lower incomes are also more likely than those with higher incomes to think it’s important for the government to make voting mandatory. The gap is largest in the U.S., where 64% of lower-income adults feel it is important to make voting compulsory, compared with 46% of middle-income adults and 38% of higher-income adults.

Though rare overall, mandatory voting laws are relatively common in Latin American countries, including Mexico, Brazil, Argentina and Peru, according to IDEA. Voting is also compulsory in Australia, Turkey, Singapore and Belgium.

In some places where voting is compulsory, the government exempts certain people from complying. This is the case in Argentina, where voting is voluntary for those ages 16 to 18, and also in Brazil, which additionally exempts those who are older than 70 and those who are illiterate.

Even though 27 countries have laws that mandate voting in national elections, such laws are enforced in only 14 of these countries. To avoid possible sanctions, individuals generally must provide a legitimate explanation for why they abstained. Sanctions imposed on nonvoters generally can include disenfranchisement or a fine, which varies by country.

In Singapore, voters who skip elections are removed from the voter registry until they reapply for inclusion and include a legitimate excuse. In Bolivia, public services such as withdrawing funds from a bank can be frozen if an individual does not show proof of voting during a three-month period following a national election.

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, its full dataset and its methodology.