Jews in the United States are on the whole less religious than the overall public, at least by standard measures used in surveys. But Jewish Americans participate in a wide range of culturally Jewish activities as well as traditional religious practices.

A new Pew Research Center report, based on a survey of 4,718 Jewish American adults fielded from Nov. 19, 2019, to June 3, 2020, takes a closer look at these and many other topics. Here are 10 key findings from the report.

Pew Research Center conducted this study to explore the breadth and diversity of Jewish Americans’ religious experiences. This survey represents the Center’s most comprehensive, in-depth study of the subject, drawing on 4,718 U.S. adults who identify as Jewish, including 3,836 Jews by religion and 882 Jews of no religion. The survey was administered online and by mail by Westat, from Nov. 19, 2019, to June 3, 2020. Respondents were drawn from a national, stratified random sampling of residential mailing addresses, which included addresses from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. No lists of common Jewish names, membership rolls of Jewish organizations or other indicators of Jewishness were used to draw the sample.

The sample is nationally representative and was weighted to align with demographic benchmarks for the U.S. adult population from the Census Bureau as well as a set of modeled estimates for the religious and demographic composition of eligible adults within the larger U.S. adult population.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and its methodology.

The size of the adult Jewish population has been fairly stable in percentage terms, while rising in absolute numbers, roughly in line with the growth of the U.S. population. An estimated 2.4% of U.S. adults are Jewish. In Pew Research Center’s first major survey of U.S. Jews in 2013, by comparison, the estimate was 2.2%. In absolute numbers, the 2020 Jewish population estimate is approximately 7.5 million, including 5.8 million adults and 1.8 million children (rounded to the closest 100,000). The 2013 estimate was 6.7 million, including 5.3 million adults and 1.3 million children.

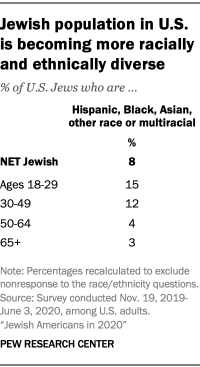

Like the overall U.S. population, Jews appear to be growing more racially and ethnically diverse. Around nine-in-ten Jewish American adults (92%) identify as non-Hispanic White, while 8% identify with other racial or ethnic categories. Among Jews ages 18 to 29, however, the share who identify as a race or ethnicity other than non-Hispanic White rises to 15%.

Overall, 17% of Jews surveyed – including 29% of Jewish adults under the age of 30 – live in households in which at least one child or adult is Black, Hispanic, Asian, some other non-White race or ethnicity, or multiracial.

U.S. Jews are less religious than American adults overall. About one-in-ten Jewish Americans (12%) say they attend religious services at least weekly in a synagogue, temple or less formal setting – such as a havurah or independent minyan – compared with about a quarter of U.S. adults who say they attend religious services weekly or more (27%).

U.S. Jews are also less likely than the overall U.S. public to say religion is “very important” to them (21% vs. 41%). Slightly more than half of Jews say religion is “not too” or “not at all important” in their lives, compared with one-third of Americans overall who say the same. There are even bigger gaps when it comes to belief in God: Around a quarter of Jews (26%) say they believe in God “as described in the Bible,” while 56% of all U.S. adults say this.

Jewish Americans are staunchly liberal and favor the Democratic Party, but Orthodox Jews are a notable exception. The survey, which was conducted in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election, finds that 71% of Jewish adults (including 80% of Reform Jews) are Democrats or independents who lean toward the Democratic Party. But among Orthodox Jews, three-quarters say they are Republican or lean that way. And that percentage has been trending up: In 2013, 57% of Orthodox Jews were Republicans or Republican leaners.

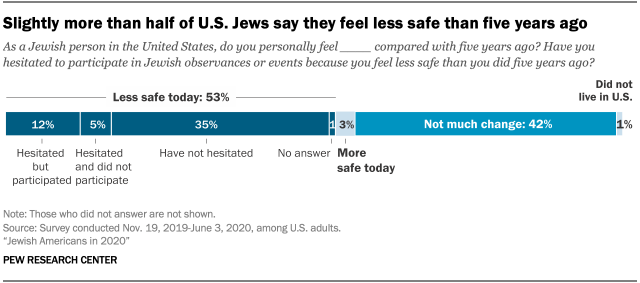

Three-quarters of American Jews think there is more anti-Semitism in the U.S. today than there was five years ago. Moreover, just over half (53%) say that, as a Jewish person in the U.S., they personally feel less safe than they did five years ago.

However, the effect on participation in Jewish activities appears to be relatively small. The vast majority of those who feel less safe say they have not hesitated to participate in Jewish observances or events because of security concerns – or that, if they did hesitate, they ultimately went ahead and participated anyway. About 10% of the Jews who feel less safe (or roughly 5% of all U.S. Jews) say they have chosen not to take part in a Jewish observance or event out of concern for their safety.

A large majority of U.S. Jews (82%) say caring about Israel is either “essential” or “important” to what being Jewish means to them. About six-in-ten (58%) say they are at least somewhat attached to Israel, and those who have been to Israel are especially likely to feel this way (79%). But there are sharp partisan differences in attitudes toward Israel. At the time of the survey – conducted during the final 14 months of President Donald Trump’s administration – Jewish Democrats and Democratic leaners were much more likely than Jewish Republicans and GOP leaners to say the U.S. was too supportive of Israel (29% vs. 5%).

Overall, more than half of U.S. Jews also gave a negative rating to Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister for more than a decade. Even so, when it comes to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, just over six-in-ten U.S. Jews (63%) say they think a way can be found for Israel and an independent Palestinian state to coexist peacefully.

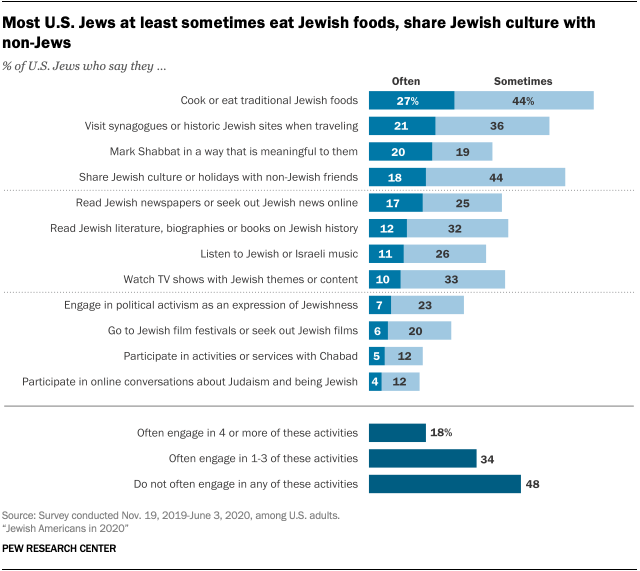

Majorities of U.S. Jews engage in cultural activities like cooking Jewish food (72%), sharing holidays with non-Jewish friends (62%) and visiting historical Jewish sites (57%). Many also say they engage with Judaism through Jewish media by “often” or “sometimes” reading Jewish literature, history or biographies (44%), watching television with Jewish or Israeli themes (43%), or reading Jewish news in print or online (42%). Those who are religiously observant in traditional ways – such as going to synagogue and keeping kosher dietary laws – also report the highest levels of engagement in the broad array of cultural Jewish activities listed in the survey.

But even among Jews who are not traditionally observant, about half say they at least sometimes take part in activities such as eating or cooking Jewish foods, and one-third say the same about visiting Jewish historical sites when traveling.

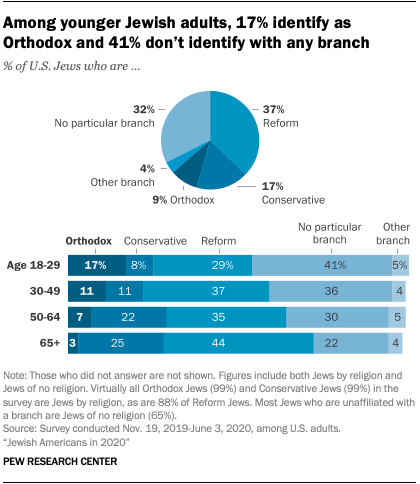

Younger Jews are more likely than older Jews to identify as Orthodox and more likely to say they do not belong to any particular branch of Judaism. Jews under 30 appear to be taking divergent paths – one steeped in traditional religious observance, the other involving little or no religious engagement. Some 17% of U.S. Jews ages 18 to 29 say they are Orthodox, compared with 3% of Jews ages 65 and older. At the same time, 41% of young Jewish adults do not identify with any particular branch of American Judaism. Most of the people in this category are “Jews of no religion” – they describe their religion as atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular, though they all have a Jewish parent or were raised Jewish and still identify as Jewish culturally, ethnically or because of their family background.

Meanwhile, the Reform and Conservative movements, American Judaism’s largest branches, seem to be losing ground with younger generations. About four-in-ten Jews ages 18 to 29 identify as Reform (29%) or Conservative (8%), compared with seven-in-ten Jews who are 65 and older (44% Reform, 25% Conservative).

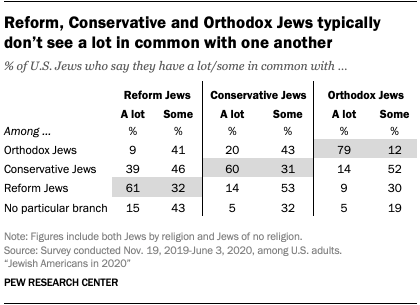

Members of different branches of American Judaism generally do not feel they have “a lot” in common with one another. About half of Orthodox Jews in the U.S. say they have “not much” (23%) or “nothing at all” (26%) in common with Reform Jews, and a majority of Reform Jews reciprocate those feelings: 39% say they have “not much” in common with the Orthodox and 21% say they have “nothing at all” in common. Just 9% of Orthodox Jews feel they have “a lot” in common with Reform Jews and vice versa. In fact, both groups are more likely to express feelings of commonality toward Jews in Israel than toward each other.

About four-in-ten married Jews (42%) have a non-Jewish spouse, but intermarriage rates differ within subgroups. For example, intermarriage is almost nonexistent among married Orthodox Jews (2%), while nearly half of all non-Orthodox Jews who are married say their spouse is not Jewish (47%). Intermarriage is more common among those who have married in recent years: Among Jewish respondents who got married since the beginning of 2010, 61% have a non-Jewish spouse, compared with 18% of Jews who got married before 1980. Intermarriage also is more common among Jews who are themselves the offspring of intermarried parents: Among married Jews who say they have one Jewish parent, 82% have a non-Jewish spouse, compared with 34% of those who report that both of their parents were Jewish.

Note: Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and its methodology.