Last March, when the coronavirus outbreak took hold of public life and forced many Americans into their homes to quarantine, some speculated that more time together for couples – and, in some cases, obstacles to accessing contraception – could result in a baby boom. Now, however, early data is pointing toward a significant drop in fertility directly related to the pandemic, both in the United States and globally, in the coming years.

Some estimate that there will be close to 300,000 fewer births in the U.S. in 2021 as a result of the outbreak. These conjectures are already coming to fruition based on provisional monthly estimates. Overall, the U.S. birth rate dropped 4% in 2020 based on provisional data, and a look at December 2020 – the month when babies conceived at the beginning of the pandemic would have been born – shows an 8% decline from the previous December, suggesting that women may have postponed pregnancies in response to the ongoing public health crisis.

This post contains updates from previously published posts, which were written by Gretchen Livingston, a former senior researcher at Pew Research Center. General fertility rates, teen birth rates and births to immigrant and U.S.-born women are based on data from the National Vital Statistics System of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), which are extracted from completed birth certificates. Completed fertility rates are derived from the U.S. Census Bureau’s June Supplement of the Current Population Survey, which produces a nationally representative sample of the non-institutionalized population of the U.S. The June Fertility Supplement was first administered in 1976 and is typically conducted every other year. Most of the CPS files used in this report are from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS-CPS) provided by the University of Minnesota. Public-use data files prior to 1986 are not readily available, so analyses of pre-1986 time points are drawn from Census Bureau tabulations.

Other advanced countries have also begun to experience declining birth rates. Italy, Japan, France and Belgium are among the nations that have reported sudden drops in births about nine months after the start of the pandemic, compared with the previous year. Some worry that a “baby bust” will create societal age imbalances and strain health care and retirement systems while also eventually stripping the economy of young workers who tend to drive innovation and growth.

Past economic downturns, including the Great Recession, have revealed a connection between economic conditions, income and fertility. The coronavirus pandemic – and its associated recession – brought on increased unemployment, school and child care closures, isolation from social networks and fear about the future, all of which are factors some women may consider before getting pregnant.

While we don’t yet know what long-term impact, if any, the pandemic will have on fertility in the U.S., here are five key facts about the nation’s recent fertility trends before the pandemic began.

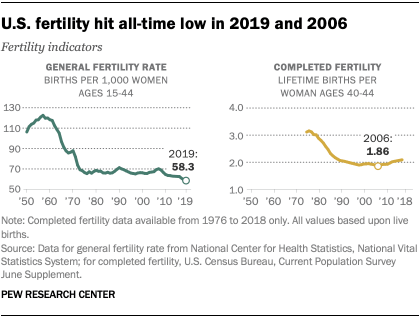

The general fertility rate in the U.S. was already at a record low before the COVID-19 pandemic began. In 2019, there were 58.3 births for every 1,000 women ages 15 to 44 in the U.S., down from 59.1 in 2018, making it the fifth consecutive year in which the fertility rate declined. A variety of factors have driven down the rate, including a decline in birth rates among women 34 and younger. The decrease also likely reflects the lingering effects of the Great Recession, as well as longer-term demographic changes such as increased educational attainment among women and delays in marriage.

The completed fertility rate, or the number of children a woman has in her lifetime, tells a slightly different story. According to this measure, the low point in U.S. fertility came in 2006, when women ages 40 to 44 had given birth to an average of 1.86 children over the course of their lifetimes. Since 2006, the completed fertility rate has been trending upward, and in 2018 the average was a little over 2.0 children. It is important to note, however, that because the completed fertility rate is a lagging indicator, it doesn’t reflect the fertility of young women today.

The share of American women at the end of their childbearing years who had ever given birth was higher in 2018 than it had been a decade earlier. Some 85% of women ages 40 to 44 were mothers in 2018, up from 82% in 2008, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of Census Bureau data. The increase in the share of women who had ever given birth, alongside the decline in the share having children in any given year, reflect the fact that women are having children later in life. The median age when women become mothers in the U.S. was 26 in 2016, up from 23 in 1994.

There has also been a striking increase in motherhood among women ages 40 to 44 who have never been married. In 2018, roughly six-in-ten (59%) of never-married women in this age group had given birth, nearly double the share in 1994 (32%).

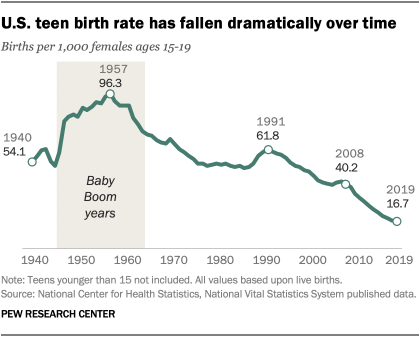

Teen birth rates have fallen dramatically in recent years. One factor that has contributed to the overall drop in annual fertility in the U.S. has been the falloff in births to teenagers. The teen birth rate hit a record low in 2019, when there were 16.7 births per 1,000 girls and women ages 15 to 19. This was a 4% drop from the previous year and less than half the teenage birth rate about a decade earlier (37.9 per 1,000 teens in 2009). The teen birth rate has fallen across all major racial and ethnic groups, but it remains higher among Hispanic and Black teens than among teens who are White or Asian. The majority of teen births in the U.S. are to unmarried mothers.

The Great Recession contributed to the overall birth rate decline, including teen births. But given that the pattern has persisted well beyond the recession, experts also attribute it to fewer teens having sex, teens having access to more reliable birth control, and pregnancy prevention programs.

Birth rates have declined for U.S.-born and foreign-born women. Still, immigrant women account for a disproportionate share of the nation’s births among women ages 15 to 44. In 2017, 14% of the U.S. population was foreign born, but 23% of all births were to immigrant women.

For decades, a large share of immigrant births in the U.S. were to mothers of Mexican descent (42% in 2000). But the demographic profile of new mothers has shifted in recent years as immigration patterns have changed. Specifically, immigration flows from Latin America have slowed and Asian immigration is on the rise. As a result, only a quarter of U.S. immigrant births were to Mexican-born women in 2018. Among immigrant women overall, half of all births in 2018 were to Hispanic women, down from 58% in 2000.

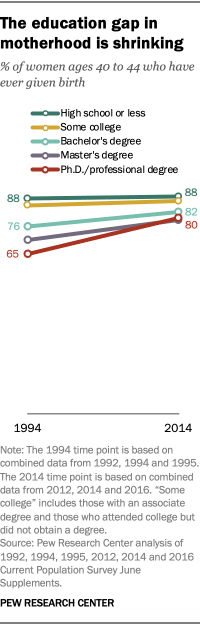

The education gap in fertility has narrowed in recent decades. Historically, women with higher levels of education have been less likely to become mothers. In 1994, 65% of women ages 40 to 44 with a Ph.D. or professional degree were mothers, as were 76% of those with four-year college degrees. The shares were considerably higher among those with less education: 87% of women with some college education and 88% of those with a high school degree or less were mothers.

In the last few decades, this gap has narrowed significantly. In 2014, 80% of women ages 40 to 44 with a Ph.D. or professional degree were mothers, as were 82% of those with a bachelor’s degree. The shares remained steady during this period among women with less education. Across all education levels, the timing of motherhood has shifted as fewer women are having children in their teens or early 20s.