The coronavirus outbreak that began in February 2020 sent shock waves through the U.S. labor market, pushing the unemployment rate to near record highs and causing millions to leave the workforce. A year later, a full recovery for the labor market appears distant. Employment in February 2021 was 8.5 million less than in February 2020, a loss that could take more than three years to recoup assuming job creation proceeds at roughly the same monthly rate as it did from 2018 to 2019. But a faster recovery is possible if the job gains seen in March 2021 are sustained in the coming months.

As it rippled through the economy, the COVID-19 downturn affected some Americans more than others. Unemployment climbed more sharply among women than men, a reversal from the trend in the Great Recession. Young adults, those with less education, Hispanic women and immigrants also experienced greater job losses. Unpartnered mothers saw a bigger drop in the share at work than other parents, and low-wage workers saw a particularly sharp decrease in employment.

Here are six facts about how the COVID-19 recession is affecting labor force participation and unemployment among American workers a year after its onset.

The U.S. labor market continues to feel the effects of the coronavirus outbreak of February 2020. With millions still out of work, Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to look at how different groups of workers have been affected during the first year of the economic downturn induced by the pandemic.

The main data source for this analysis is the Current Population Survey (CPS). The CPS is the U.S. government’s official source for monthly estimates of unemployment. In this report, monthly CPS files from each year were analyzed separately to generate monthly estimates for 2020 and 2021. The Census Bureau incorporates updated population estimates in the CPS each January, and this may affect the comparability of some statistics over time. Most of the CPS microdata files used in this report are the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS-CPS) provided by the University of Minnesota. Estimates in this report are not seasonally adjusted.

The COVID-19 outbreak has affected data collection efforts by the U.S. government in its surveys, limiting in-person data collection and affecting the response rate. It is possible that some measures of labor market activity and how they vary across demographic groups are affected by these changes in data collection. For example, in February 2021, the not seasonally adjusted unemployment rate may have been as high as 7.0%, instead of the 6.6% officially reported, if an adjustment is made for measurement errors, per BLS reports.

Our analysis includes an “adjusted” unemployment rate which accounts for the measurement error reported by the BLS. In addition, we adjust the unemployment rate to account for the drop in the labor force participation rate in a given month compared with the same month the previous year. For example, the labor force in February 2021 is estimated two ways – once by applying the participation rate in February 2020 to the working-age population in February 2021 and again by applying the participation rate in February 2021 to the same working-age population. The difference in the two numbers is added to the unemployed population for February 2021 to compute the adjusted unemployment rate.

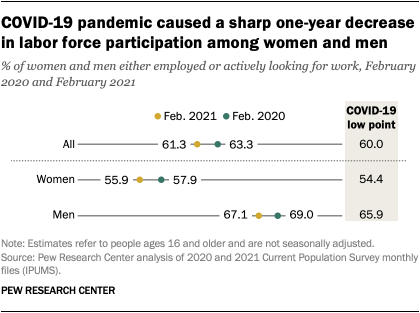

More women than men quit the labor force in the first year of the COVID-19 recession. From February 2020 to February 2021, a net 2.4 million women and 1.8 million men left the labor force – neither working nor actively looking for work – representing drops of 3.1% and 2.1%, respectively. Women accounted for a majority of the decrease in the labor force in the first year of the downturn even though they make up less than half of the U.S. workforce.

Looked at another way, the shares of women and men (ages 16 and older) participating in the labor force – at work or actively looking for work – have fallen notably during the pandemic. For women, the labor force participation rate in February 2021 was 55.9%, compared with 57.9% a year earlier. For men, the rate fell from 69.0% to 67.1% over this period. The decrease in the labor force participation rate for workers overall – from 63.3% to 61.3% – exceeds that seen in the Great Recession and ranks among the largest 12-month declines in the post-World War II era, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Although lower than a year ago, the labor force participation rate has risen in recent months. The rate for women had fallen as low as 54.4% in April 2020, and the rate for men had dipped to 65.9% in the same month. Since then, the recovery appears to have been somewhat sharper for women.

The changes in labor force participation in the COVID-19 downturn stand in sharp contrast to the Great Recession, when men were more deeply affected. From December 2007 to December 2009, the number of women who left the labor force (84,000) was modest in comparison with the number of men who did the same (929,000). Also, the labor force participation rate for women decreased by 1 percentage point over this period of the Great Recession, compared with 2 points for men.

The key difference between the two recessions is that job losses in the pandemic have been concentrated in service sectors in which women account for the majority of employment, such as leisure and hospitality and education and health services. More typically, job losses in recessions, including the Great Recession, have centered around goods-producing sectors, such as manufacturing and construction, in which men account for the greater share of employment.

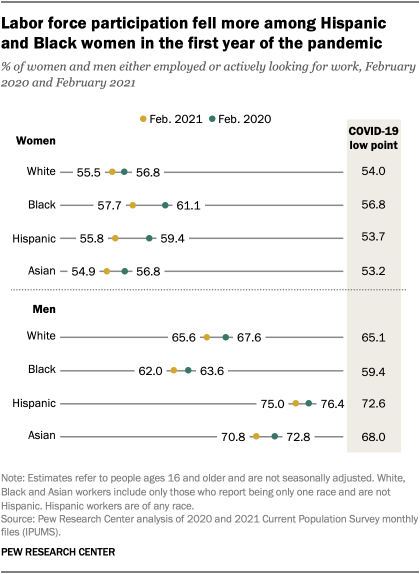

Hispanic and Black women accounted for much of the decrease in labor force participation among women. The net 2.4 million women who left the labor force from February 2020 to February 2021 included 582,000 Hispanic women and 511,000 Black women. Collectively, Hispanic and Black women accounted for 46% of the total decrease among women but represent less than one-third of the female labor force in the U.S.

This was also reflected in the changes in the labor force participation rates. From February 2020 to February 2021, the decrease in the rate among Hispanic and Black women was 3.6 and 3.4 percentage points, respectively. For Asian women it was 1.9 points, while for White women it was 1.3 points.

One reason Hispanic women may have been more likely to leave the labor force is that they have a greater presence than other women or men in the leisure and hospitality sector. This sector has shed more jobs than any other sector in the economy from February 2020 to February 2021. Pandemic-driven pressures on parents may also have affected Hispanic, Black and Asian women more than White women. Compared with other women with children at home, Hispanic and Black women are more likely to be unpartnered parents.

There is little difference in how the labor force participation rate changed among White, Black, Hispanic and Asian men. White and Asian men experienced a similar drop in the labor force participation rate as White and Asian women – about 2 percentage points or less. But the decrease in the rate among Black and Hispanic men – roughly 1.5 points each – appears to have been less than the decrease among Black and Hispanic women, about 3.5 points each.

The decrease in labor force participation suggests that the official unemployment rate understates the share of Americans who are out of work. Workers who left the labor force during the pandemic are not counted among the unemployed, as per usual practice. As the economy improves, many of these workers may reenter the labor market, adding to the number currently counted as unemployed and in want of work. For that reason, Jerome Powell, chair of the Federal Reserve board of governors, recently suggested that those who left the labor force since February 2020 should be counted among the unemployed to gain a better understanding of the slump in the labor market.

Adjusting the unemployment rate for labor force exits, and also making a correction for measurement challenges that have affected government surveys in the pandemic, shows that the U.S. unemployment rate in February 2021 may have been as high as 9.9%, instead of 6.6% as officially reported.

The difference between the official and the adjusted unemployment rates was highest in April 2020. In that month, the official rate stood at 14.4%, compared with an adjusted rate of 22.7%. The labor force participation rate had dipped to 60.0% in April, the lowest rate recorded in 2020, and measurement issues also loomed large in the government surveys.

Both the official and the adjusted unemployment rates have trended downward since April 2020. However, a gap of about 3 percentage points has persisted between the two measures since June 2020. It should be emphasized that the adjusted rate assumes that all workers who left the labor force during the pandemic will return in search of work in the near future. Other researchers have proposed that a more realistic unemployment rate may be closer to 8% at the moment.

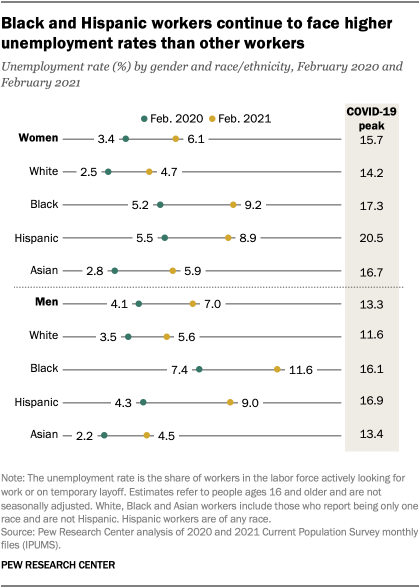

After a sharper increase earlier in the pandemic, the unemployment rate for women likely was on par with the rate for men in February 2021. The initial wave of the pandemic sent the unemployment rate for women soaring from 3.4% in February 2020 to 15.7% in April 2020, as officially reported. Men also experienced a spike, but less so than women, as their unemployment rate increased from 4.1% to 13.3% over this period.

By February 2021, the official unemployment rate for women (6.1%) had fallen below the rate for men (7.0%), not seasonally adjusted. However, since labor force participation fell more among women than men, the adjusted unemployment rate for women (9.8%) was similar to the rate for men (9.9%) in February 2021.

Unemployment remained more elevated among Black and Hispanic workers. Roughly one-in-ten Black and Hispanic workers, women or men, were unemployed in February 2021, based on the official unemployment rate. Black men (11.6%) were unemployed at a higher rate than other men or women. By comparison, only about 6% of White and Asian workers or fewer, women or men, were unemployed in February 2021.

As business operations ramped up more recently, the unemployment rate decreased for all groups of workers. Among Black women, the unemployment rate dropped from a peak of 17.3% in May 2020 to 9.2% in February 2021. Among Black men, the rate fell from a high of 16.1% in June 2020 to 11.6% in February 2021.

White women saw a decrease in their unemployment rate from a peak of 14.2% in April 2020 to 4.7% in February 2021. Over the same period, White men’s unemployment rate decreased from a peak of 11.6% to 5.6% in February 2021. Asian men and women also saw significant reductions from their peak unemployment rates of roughly 9 or more percentage points each. In February 2021, Asian women had an unemployment rate of 5.9%, while the rate for Asian men was 4.5%.

In April 2020, Hispanic women had a peak unemployment rate of 20.5%, while Hispanic men had an unemployment rate of 16.9%. But Hispanic women (8.9%) and men (9.0%) had unemployment rates similar to each other in February 2021.

Despite recent improvements, unemployment rates for all major racial and ethnic groups of workers were substantially higher in February 2021 than in February 2020. For example, while the unemployment rate for White women (4.7%) was lower than among other women, it was nearly double the rate they experienced in February 2020. That was also the case among Asian women, whose unemployment rate increased from 2.8% in February 2020 to 5.9% in February 2021.

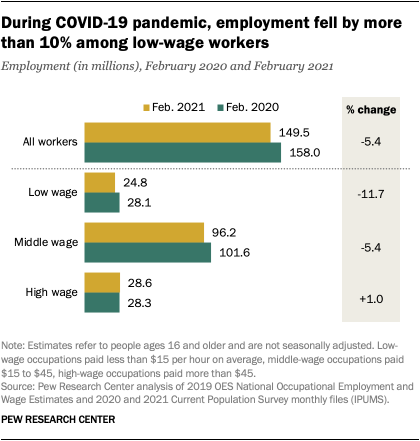

Workers in low-wage jobs experienced the greatest drop in employment. From February 2020 to February 2021, employment among low-wage workers fell by 11.7%, from 28.1 million to 24.8 million. This compares with a loss of 5.4% among middle-wage workers, whose employment fell by 5.5 million over the period. Meanwhile, employment among high-wage workers was roughly unchanged, at slightly more than 28 million.

The reason for this pattern is that the COVID-19 recession is centered in the services sector, especially in the leisure and hospitality industry, which has been hit hardest in the pandemic and accounts for many of the low-wage jobs. The trend in the current recession stands in contrast with the Great Recession, which saw middle-wage occupations shed jobs at a higher rate than other occupations.