Online harassment is often subjective when it comes to how people perceive the unpleasant or offensive behaviors that they encounter. Indeed, a notable share of Americans who have personally been targets of troubling online behaviors would not label their experience as “online harassment,” according to a new Pew Research Center report.

The Center’s survey conducted last September measured online harassment by asking respondents if they had personally experienced any of the following: offensive name-calling, purposeful embarrassment, stalking, physical threats, sexual harassment and sustained harassment. But in order to get a better understanding of how subjective this concept is, targets of these behaviors were asked if they considered their most recent incident to be “online harassment.”

Pew Research Center has been studying online harassment for years. This particular report focuses on American adults’ experiences and attitudes related to online harassment. For this analysis, we surveyed 10,093 U.S. adults from Sept. 8 to 13, 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

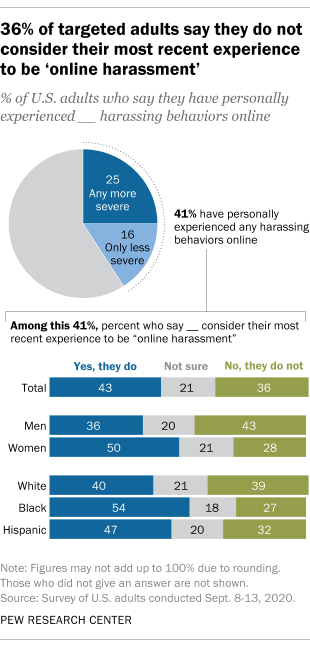

Some 41% of U.S. adults say they have ever experienced at least one of those activities and were categorized for our research as targets of online harassment. But when asked questions about the most recent episode they had encountered, even some of those who had been subjected to the more severe forms of online abuse say they would not classify it as harassment or are unsure it constituted harassment.

Among adults who report having experienced at least one harassing behavior online, roughly four-in-ten (43%) say that they consider their most recent experience to be “online harassment,” while 36% say they would not classify this experience as “online harassment.” An additional 21% say they are unsure.

Women who have experienced harassing behaviors online are more likely than their male counterparts to say they consider their most recent experience to be “online harassment” (50% vs. 36%). Conversely, a greater share of men than women who have experienced harassing behaviors online say they do not consider their most recent experience to be “online harassment” (43% vs. 28%).

In addition, Black (54%) and Hispanic adults (47%) who were targets of online harassment are more likely to label their experience as “online harassment” than are White targets (40%). On the other hand, a greater share of White targets say they don’t see their most recent experience as “online harassment” compared with their Black counterparts (39% vs. 27%).

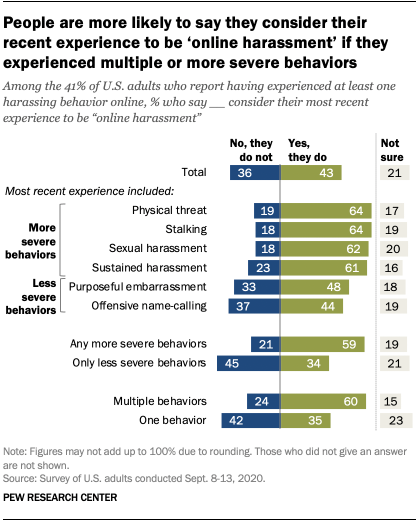

The Center analysis broke the six harassment behaviors into several different groups. Some 38% of those who had been targeted had ever experienced only less severe problems – offensive name-calling or purposeful embarrassment – while 62% had ever experienced at least one of the more severe forms of harassment: physical threats, stalking, sexual harassment or sustained harassment. In their most recent encounter, 34% of targets said they had encountered one of these more severe behaviors, while 31% had faced multiple behaviors (i.e., more than one of the six behaviors we asked about).

A plurality of people who faced only less severe harassing behaviors in their most recent encounter (45%) say that they would not call this experience “online harassment,” whereas at least six-in-ten targets of each of the more severe behaviors say they would call their experience “online harassment.” Among those who only faced less severe behaviors in their most recent incident, roughly a third say they consider their experience to be “online harassment.” This pattern is statistically similar to what was seen in 2017.

While people who have faced more severe forms of harassment are more likely to label it as such, there remain notable shares who are not sure how they would characterize the problem they encountered. Roughly a third or more of those who have been physically threatened (36%), stalked (36%), sexually harassed (38%) or harassed for a sustained period of time (39%) in their most recent encounter say they do not consider this experience to be “online harassment” or are unsure about calling it this.

Beyond the types of behaviors encountered, the number of behaviors involved also plays a role in how people label their experience. While 35% of people who only faced one type of behavior in their most recent encounter would call it “online harassment,” 60% of adults who faced multiple types of harassing behaviors in their most recent experience would say it was “online harassment.”

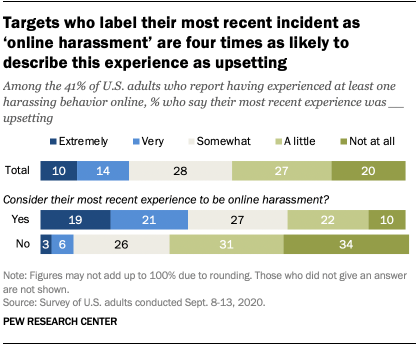

There is a strong relationship between the reaction people have to their most recent incident and the way they classify it. Those who do not characterize their most recent episode as harassment are also less likely to say they were bothered by what happened. In fact, 65% of those who do not describe the episode as harassment say their most recent experience was not at all (34%) or a little (31%) upsetting, while 33% of targets who refer to their most recent experience as “online harassment” say the experience was not at all or a little upsetting.

Conversely, those who call their experience “online harassment” are more than four times as likely to describe that experience as very or extremely upsetting compared with those who would not use that label (40% vs. 9%). More pointedly, about one-in-five targets (19%) who call their experience “online harassment” say their most recent experience was extremely upsetting, while only 3% of those who reject the label of “online harassment” say the same.

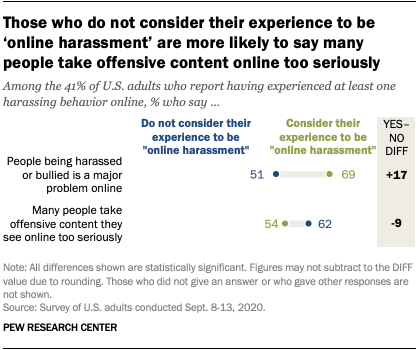

Beyond their personal experiences, those who do not call their recent experience “online harassment” are less likely to see online harassment as a major problem. Roughly seven-in-ten people (69%) who call their most recent experience “online harassment” say that harassment is a major problem online, whereas about half of those (51%) who would not use this classification say the same – on par with findings from 2017. These differences in opinion hold up even when controlling for severity of the harassment, gender and race or ethnicity.

In addition, about six-in-ten targets (62%) who do not consider their most recent brush with harassing behavior to be “online harassment” say many people take offensive content they see online too seriously, compared with 54% of those who would describe their experience in this way. While the pattern remains the same, the difference between these groups has shrunk a notable degree since 2017, when there was a 23 percentage point gap (73% vs. 50%).

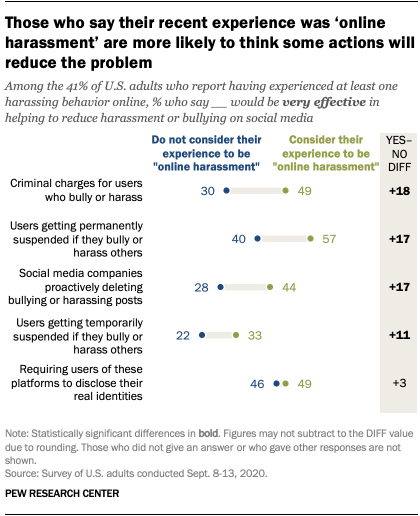

People who would not call their most recent experience “online harassment” are also less optimistic about the efficacy of a variety of tactics for combatting harassment on social media. They are 18 points less likely to say criminal charges and 17 points less likely to say permanent bans for users who bully or harass others would be very effective in helping to reduce harassment or bullying on social media, compared with targets who classify their most recent experience as “online harassment.”

There are also double-digit differences between those who label their online experiences as harassment and those who don’t when it comes to their views regarding the effectiveness of social media companies proactively deleting bullying or harassing posts and temporary bans for users who bully or harass others. No differences are seen in their views of the effectiveness of requiring users of these platforms to disclose their real identities in curtailing harassment.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.