Americans just aren’t picking up the phone much anymore. Eight-in-ten Americans say they don’t generally answer their cellphone when an unknown number calls, according to newly released findings from a Pew Research Center web survey of U.S. adults conducted July 13-19, 2020.

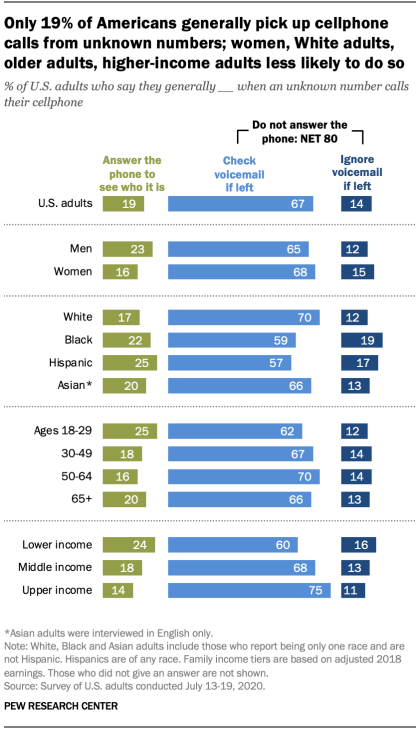

But not all Americans are equally likely to ignore these calls. While, at most, a quarter of Americans from any demographic group say they generally answer the phone for an unknown number – and 19% of U.S. adults overall say they do so – men are more likely than women to answer the phone. And though much has been made of younger adults’ distaste for phone conversations, the survey finds that Americans ages 18 to 29 are more likely to take calls from unknown numbers than those in older age groups. In addition, Hispanic and Black adults are more likely than White adults to say they generally pick up for a number they don’t recognize, as are those living in households with lower income levels compared with those from middle- and higher-income households.

Pew Research Center conducted this research to explore Americans’ behavior and attitudes during the coronavirus outbreak. As part of a larger report investigating the challenges of contact tracing, we asked individuals about their general behavior surrounding unknown calls and their perceptions of scams.

To explore this, we surveyed 10,211 U.S. adults from July 13 to 19, 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

This survey includes a total sample size of 298 Asian Americans. The sample includes English-speaking Asian Americans only and, therefore, may not be representative of the overall Asian American population (75% of our weighted Asian American sample was born in another country, compared with 77% of the Asian American adult population overall). Despite this limitation, it is important to report the views of Asian Americans on the topics in this study. As always, Asian Americans’ responses are incorporated into the general population figures throughout this report. Because of the relatively small sample size and a reduction in precision due to weighting, we are not able to analyze Asian American respondents by demographic categories, such as gender, age or education.

For information about how we defined income tiers, see the report’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

The majority of Americans (67%) say their general practice is to not answer the phone when an incoming call is from an unknown number but to check a voicemail if one is left. The share of Americans who say they generally ignore any voicemail left after not answering a call is relatively low (14%) but does vary by gender, race and ethnicity, and income level.

People’s reluctance to pick up phone calls they don’t recognize can affect a variety of activities, including participation in contact tracing programs to identify and isolate those who have contracted COVID-19. Recent reports suggest that some public health authorities are struggling to make contact with those who have been exposed to COVID-19.

A key finding from the Center’s survey is that those who say they generally ignore both a call and a voicemail are less likely to also say they’d be fully comfortable or likely to engage with contact tracing protocols – that is, speaking with a public health official, sharing relevant information and quarantining if told they had the coronavirus.

Less clear is why Americans are not picking up their phones. Some might be overwhelmed by robocalls, others might be taking advantage of call blocking technology and some might screen calls for reasons related to their work or their daily routines.

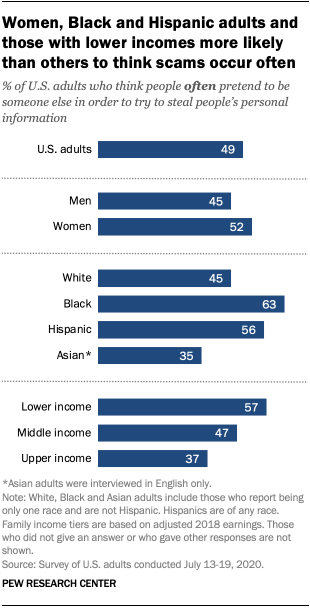

One other factor could be concerns about scams, some new versions of which have emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Center’s survey found that nine-in-ten U.S. adults think people often (49%) or sometimes (42%) pretend to be someone else in order to try to steal people’s personal information.

On this issue, Americans vary in their perceptions that people often pretend to be someone else to try to steal information in this way. About half of women say this, compared with a smaller share of men. Roughly six-in-ten Black adults (63%) say the same, compared with 56% of Hispanic adults, 45% of White adults and 35% of Asian adults. And those with relatively low incomes are more likely to think people do this often (57% say so) compared with smaller shares of those with higher incomes.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.