A record number of votes – about 65 million – were cast via mail ballot (also called absentee voting) in the 2020 general election, and the outcome of the presidential race in several key states came down to them. Although former Vice President Joe Biden has been declared the winner over President Donald Trump, the final allotment of electoral votes may be determined by the remaining mail/absentee ballots, as well as provisional votes that were cast on Election Day and special absentee ballots submitted by military and overseas voters.

Final, certified counts from this election won’t be available for a few weeks or longer, depending on recounts and legal challenges. But we can get some sense of how many mail, provisional and military and overseas ballots will and won’t get counted – and why – by looking at the past two even-year elections.

Given the sheer number of absentee and mail ballots cast this year, and the intense focus on counting or excluding them as keys to either President Donald Trump or former Vice President Joe Biden getting to 270 electoral votes, we wanted to look at the two most recent presidential and midterm elections to see how many such ballots went uncounted. We also examined provisional ballots and military and overseas votes, for similar reasons.

Our main data sources were the 2016 and 2018 Election Administration and Voting Surveys, conducted biennially by the U.S. Electoral Assistance Commission. We also used the EAC’s “Comprehensive Reports” for those two years, which are based on the EAVS surveys.

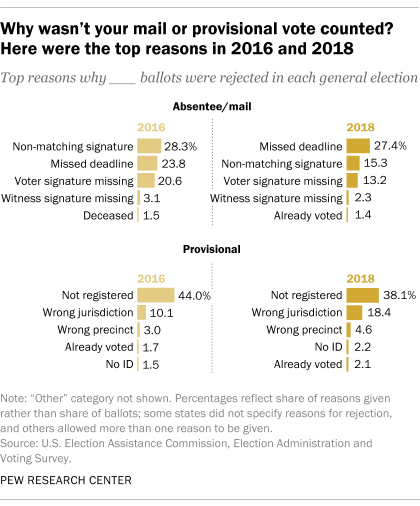

Among the questions the EAVS asks is the reason why a mail, provisional, or military and overseas ballot was rejected. However, some states did not specify reasons for rejection, and a handful allowed more than one reason per ballot to be given. In references to rejection reasons, percentages reflect the share of total reasons given, rather than total ballots.

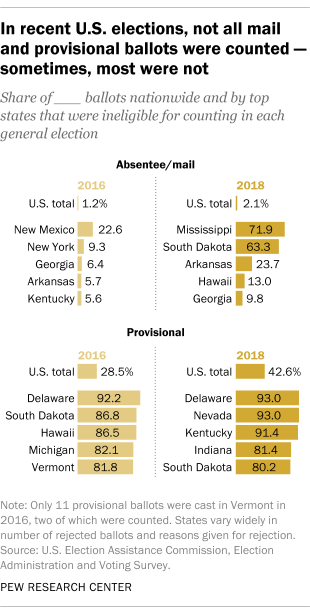

In the 2016 general election, voters submitted nearly 33.5 million mail ballots, but more than 400,000 (1.2% of the total) weren’t counted, according to data from that year’s Election Administration and Voting Survey. In 2018, 2.1% of the 30.2 million domestic civilian mail ballots, or nearly 628,000 votes, didn’t make the cut.

Both years, the most common reasons cited for rejecting mail ballots included missing the state’s deadline for getting them in, not signing the ballot, and mismatches between the signature on the ballot and the one on file at the elections office. Less-common reasons included the voter having died, the ballot not including a witness signature (in the more than a dozen states that required one) and the person already having voted.

In 2016, the share of uncounted mail ballots ranged from 0.2% in the District of Columbia to 22.6% in New Mexico. In more than half of states (31 plus D.C.), fewer than 2% of mail ballots went uncounted.

The odds were considerably longer for provisional ballots. Since 2002, federal law has required most states to let people vote provisionally at the polls on Election Day even if they cannot prove registration or their eligibility is questioned. Provisional ballots are separated from other ballots and counted later, assuming election officials have confirmed the voter’s eligibility.

In 2016, nearly 2.5 million people voted provisionally, according to the EAVS data. However, only about 1.5 million of those provisional ballots were fully counted – 214,000 more were counted in part, which some but not all states allow. (For example, if a person was registered to vote but cast a provisional ballot in the wrong district, his vote for president could be recorded but not his vote for state legislator.) All told, 28.5% of all provisional ballots cast – nearly 700,000 – ultimately weren’t counted.

In the 2018 off-year elections, just over 1.8 million people cast provisional ballots. A little over half of them eventually were counted in full, another 101,000 or so were partially counted, and nearly 790,000, or 42.6%, weren’t counted at all.

Given the nature of provisional ballots, it’s perhaps not surprising that the most common reason they were rejected was that the voter was not registered. This accounted for 43.9% of reasons given in 2016 and 38.1% in 2018. In both years, the next most common reason given was that the voter, while registered in their state, had tried to vote in the wrong jurisdiction or precinct.

States run the gamut in how many provisional ballots they count. Delaware led all other states in rejecting provisional ballots in both 2016 and 2018, counting fewer than 10% of them. At the other end of the range, Maine counted in full all 193 provisional ballots cast in 2016 and all 315 that were submitted in 2018.

Members of the military who are away from their usual voting residence, their family members and U.S. citizens living overseas can also vote in U.S. elections, using special absentee ballots. While their numbers may be small (only about 660,000 people sent in military and overseas ballots in 2016, about 0.5% of all voters), they could potentially help decide very close races.

Most ballots cast by military and overseas voters do get counted. In 2016, nearly 81% of such ballots were counted by the states, according to a report by the Electoral Assistance Commission. In 2018, only 5.7% of such ballots were rejected. Missing the state return deadline was the most common reason cited for rejecting military and overseas votes.