Government restrictions on religion rose to a record high in 2018, while religion-related social hostilities fell slightly but remained near peak levels, according to Pew Research Center’s 11th annual study of restrictions on religion.

Restrictions by governments include official laws and actions that curtail religious beliefs and practices, while social hostilities encompass everything from religion-related armed conflict to harassment over clothing. The analysis covers policies that were in place and events that occurred in 198 countries and territories in 2018, the most recent year for which data was available.

Here are key findings from the report.

This is the 11th in a series of annual reports by Pew Research Center analyzing the extent to which governments and societies around the world impinge on religious beliefs and practices. The studies are part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world.

To measure global restrictions on religion in 2018 – the most recent year for which data is available – the study rates 198 countries and territories by their levels of government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion. The new study is based on the same 10-point indexes used in the previous studies.

- The Government Restrictions Index measures government laws, policies and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices. The GRI comprises 20 measures of restrictions, including efforts by government to ban particular faiths, prohibit conversion, limit preaching or give preferential treatment to one or more religious groups.

- The Social Hostilities Index measures acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society. This includes religion-related armed conflict or terrorism, mob or sectarian violence, harassment over attire for religious reasons, or other religion-related intimidation or abuse. The SHI includes 13 measures of social hostilities.

To track these indicators of government restrictions and social hostilities, researchers combed through more than a dozen publicly available, widely cited sources of information, including the U.S. State Department’s annual reports on international religious freedom and annual reports from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, as well as reports from a variety of European and United Nations bodies and several independent, nongovernmental organizations. Classification of regime types comes from the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index and is reused with permission of the Economist Intelligence Unit. (See Methodology for more details on sources used in the study.)

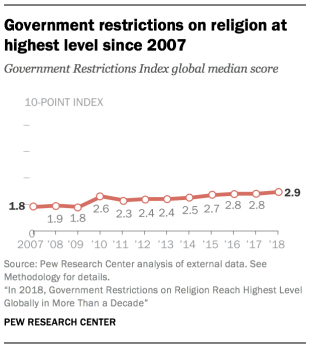

Government restrictions in 2018 were at their highest level since 2007, when Pew Research Center began tracking these trends. The global median score on the Government Restrictions Index (a 10-point scale based on 20 indicators) rose to 2.9 in 2018 from 2.8 a year earlier. That was partly due to an increase in the number of governments using force – such as detentions and physical abuse – to coerce religious groups.

While the index increase in 2018 was relatively small, government restrictions have grown substantially from a median score of 1.8 in 2007. At the same time, the number of countries with “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions has also been climbing. Most recently, 56 countries – or 28% of all 198 countries and territories in the study – fell into one of those two categories.

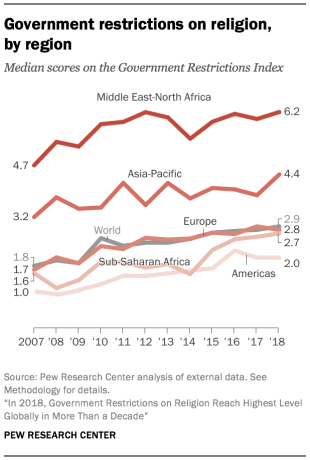

Asia and the Pacific had the largest increase in government restrictions, while the Middle East and North Africa region continued to have the highest median level of restrictions. The median score among the Asia Pacific region’s 50 countries rose to 4.4 in 2018 from 3.8 a year earlier. In 2018, roughly six-in-ten countries in the region (62%) experienced some level of government force related to religion, up from about half (52%) in 2017. In Burma, also known as Myanmar, thousands of people from religious minorities continued to be displaced. And in Uzbekistan, at least 1,500 Muslims remained in prison on charges of extremism or membership in banned groups.

As in past years, the median government restrictions score in the Middle East and North Africa remains high (6.2 out of 10). Most countries in the region had reports of governments harassing religious groups, interfering in worship, favoring some religious groups and using force against others. In Algeria, for example, authorities detained several Christians for violating a ban on proselytizing by non-Muslims. Separately, authorities in the country also prosecuted 26 Ahmadi Muslims for “insulting the precepts of Islam.”

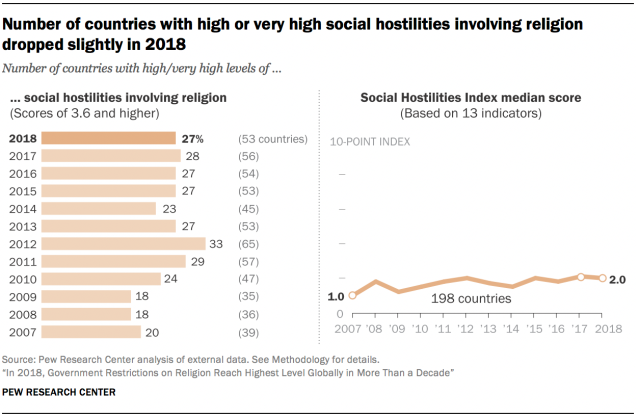

Social hostilities fell slightly in 2018 but remained near the 2017 peak. The median level of religion-related hostilities by private individuals, organizations or groups in society fell to 2.0 from 2.1 on the 10-point Social Hostilities Index. While this index has doubled in the past decade, it has seen more year-to-year fluctuations compared with government restrictions. The decline in 2018 is partly due to fewer reports of incidents in which some religious groups (usually of a majority faith in a country) attempted to prevent other religious groups (usually of minority faiths) from expressing their beliefs. Globally, the number of countries with “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities involving religion stood at 53 in 2018, or 27% of all countries studied.

Among the 25 most populous countries, India, Egypt, Indonesia, Pakistan and Russia had the highest overall levels of restrictions involving religion, according to an analysis that combines government restrictions and social hostilities. China had the highest levels of government restrictions, and India had the highest levels of social hostilities – not just among the most populous countries, but among all 198 countries in the study. The Government Restrictions Index score for China – whose government restricts religion in a variety of ways, including banning entire religious groups – was the highest ever for any country (9.3 out of 10). India’s score on the Social Hostilities Index was 9.6 out of 10, near its peak score of 9.7 in 2016, in part due to mob violence related to religion and hostilities over conversions. India also ranks high on government restrictions and reached an all-time high in its government restrictions score (5.9 out of 10).

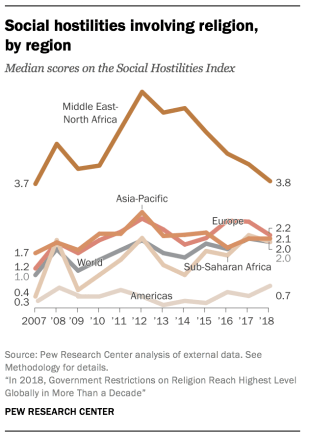

Among the five regions included in the study, only the Americas experienced an increase in social hostilities levels. The largest increase within the Americas occurred in El Salvador, where in March, during Catholic Holy Week, armed men robbed a priest and his companions on their way to Mass and killed the priest. Still, the Americas continued to have the lowest overall median level of social hostilities of the five geographic regions analyzed in the study. Social hostilities scores in Asia and the Pacific remained stable, and three other regions – sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and the Middle East-North Africa – experienced declines.

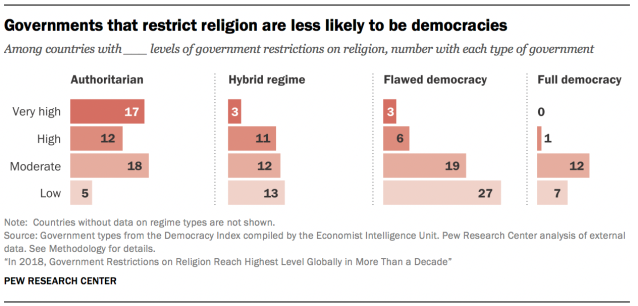

Authoritarian governments are more likely to restrict religion. For the first time, Pew Research Center included in its study a classification of regime types published in a Democracy Index by the Economist Intelligence Unit. According to the new analysis, roughly two-thirds (65%) of countries with “very high” government restrictions are classified as authoritarian. Meanwhile, only 7% of countries with “low” government restrictions are authoritarian. In terms of social hostilities involving religion, the picture is more mixed. Nevertheless, many authoritarian countries had “low” or “moderate” levels of social hostilities. No country that was classified as a full democracy had “very high” government restrictions or social hostilities.

Christians and Muslims continue to be harassed in the most countries. Harassment against religious groups, both by governments and individuals or social groups, was reported in 185 out of the 198 countries in 2018. That figure, which includes any country that had at least one incident of harassment reported against a religious group, was down slightly from 187 a year earlier. Christians and Muslims – who make up the largest faith groups globally and are more geographically dispersed than other groups – experienced harassment in the highest number of countries (145 and 139 countries, respectively). Jews are only 0.2% of the global population but were harassed in the third-highest number of countries (88). Religiously unaffiliated people – defined as atheists, agnostics and those who don’t identify with any religion – saw the largest decline in harassment of any group. These “nones” were harassed in 18 countries in 2018, down from 23 countries a year earlier.