On Nov. 3, millions of Americans will trek to their local polling places to cast their ballots for the next president. That evening, after the polls close, they’ll settle down in front of their televisions to watch the returns roll in from across the country. Sometime that night or early the next morning, the networks and wire services will call the race, and Americans will know whether President Donald Trump has won a second term or been ousted by former Vice President Joe Biden.

Just about every statement in the previous paragraph is false, misleading or at best lacking important context.

Over the years, Americans have gotten used to their election nights coming off like a well-produced game show, with the big reveal coming before bedtime (a few exceptions like the 2000 election notwithstanding). In truth, they’ve never been quite as simple or straightforward as they appeared. And this year, which has already upended so much of what Americans took for granted, seems poised to expose some of the wheezy 18th- and 19th-century mechanisms that still shape the way a president is elected in the 21st century.

Here’s our guide to what happens after the polls close on election night. While you may remember some of the details from high school civics class, others were new even to us. Keeping them in mind may help you make sense of what promises to be an election night like no other.

Between the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, fierce partisanship and intense public interest, this year’s elections are likely to play out rather differently than Americans have gotten used to. We developed this explainer to help people understand how, and why, the complex U.S. electoral process is even more so this time around.

Much of the procedural description was derived from various reports and background papers from the Congressional Research Service. Data on current state rules regarding mail-ballot deadlines, ballot-processing timetables and the binding of presidential electors was obtained – and if necessary cross-checked – from CRS, the National Conference of State Legislatures, individual state election authorities and state statutes. Historical data on absentee/mail voting trends came from our analysis of data from the U.S. Electoral Assistance Commission.

By Election Day, much of the voting already will have happened

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, Americans had been shifting away from lining up at the polls on Election Day. In 2016, only 54.5% of all ballots nationwide were actually cast in person on Election Day, according to data from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. The share was roughly the same (55.4%) in the 2018 midterms.

More people than ever before are likely to vote in person before Election Day, by absentee or mail ballot, or by taking ballots they’ve filled out at home to a drop box or other secure location. Close to half (47.3%) of the ballots cast in this year’s primary season (among the 37 states, plus the District of Columbia, for which data was available) were by absentee or mail ballot or by voting early in person. As of Oct. 28, more than 75 million voters already had cast ballots.

Counting the votes will take longer than usual

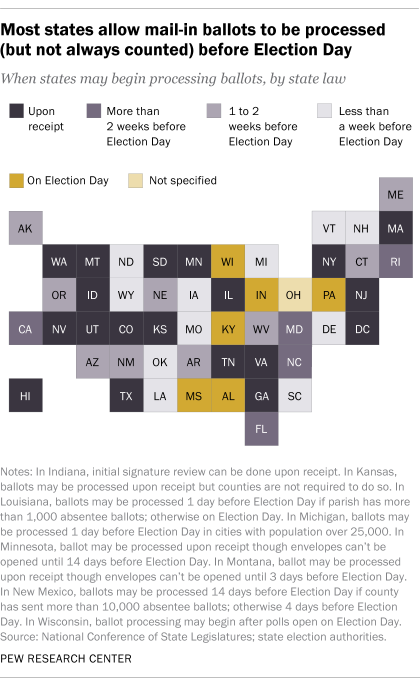

Mail ballots pose a challenge to election workers, because they must be manually removed from their envelopes and verified as valid before they can be fed into the tabulating machines. Although election workers in at least 33 states can start processing ballots (but not, in most cases, counting them) a week or more before Election Day, these counts may not be finished by election night depending on how many come in. In a half-dozen states, including the battlegrounds of Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, processing can’t start until Election Day itself.

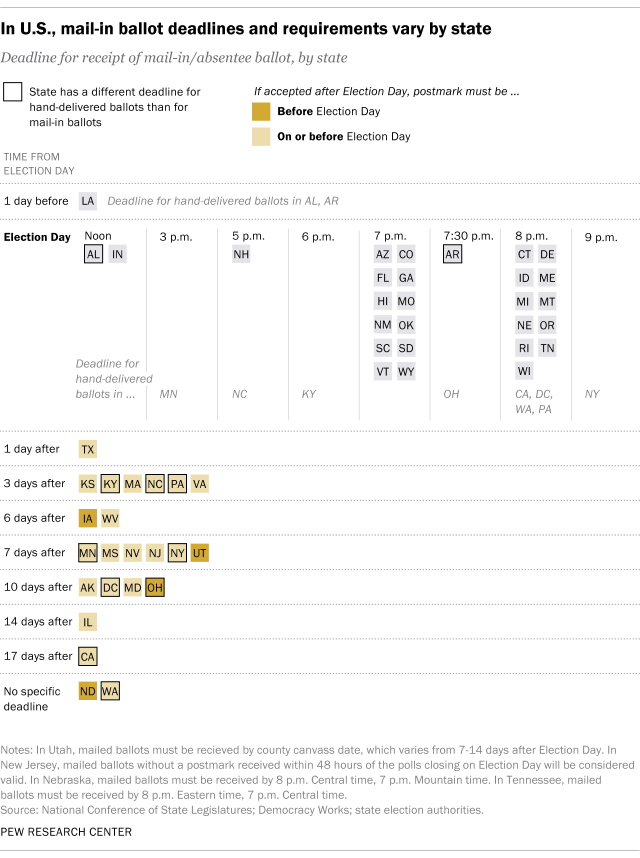

Also, in 22 states (plus D.C.), mail ballots postmarked by Election Day (or in a few cases the day before) can still be counted even if they arrive days later – further lengthening the counting process. Bottom line: Any vote totals reported on election night will be even more unofficial than they typically are.

It’s all about the electors

Unlike other U.S. elections, in which voters pick the winners directly, those millions of presidential votes won’t actually be cast for Trump or Biden. Instead, they’ll count toward a statewide tally to select the electors – the mostly little-known men and women who will actually elect the president.

Each state has as many electoral votes as it has senators and representatives combined (or, in the case of the District of Columbia, as many as it would have if it were a state). There are 538 in total, with 270 votes needed to win. As the Congressional Research Service puts it, the electors “tend to be a mixture of state and local elected officials, party activists, local and state celebrities, and ordinary citizens.”

In all but two states, the candidate with the most popular votes statewide (regardless of whether it’s a majority or a plurality) gets all that state’s electoral votes. Maine and Nebraska do it differently: The statewide popular-vote winner gets two of the electoral votes, and the winner in each House district gets an electoral vote. That’s why Democrats this year are targeting Nebraska’s 2nd District and Republicans have their eyes on Maine’s 2nd District. Both parties hope to squeeze a precious electoral vote out of a state that’s otherwise likely to go against them.

A key date in making this year’s election outcome final: Dec. 14

According to federal law, each state will have until Dec. 8 this year to resolve any “controversy or contest” concerning the appointment of its slate of electors under its own state laws. That effectively gives states more than a month after Election Day to settle any challenges to their popular votes, certify a result and award their electoral votes. If they do so by this “safe harbor” date, Congress is bound to respect the result. (The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2000 ruling in Bush v. Gore involved whether Florida was properly applying its own recount rules, and whether those rules ran afoul of the Constitution’s equal-protection guarantee.)

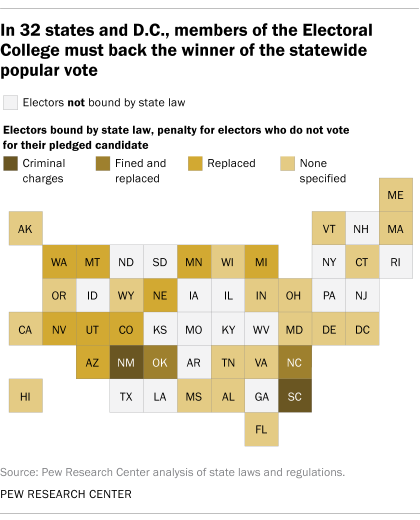

The electors will meet in their respective states on Dec. 14 – officially, the Monday after the second Wednesday in December – and formally cast their votes for president and vice president. The Constitution expressly forbids them from meeting as a single nationwide group, a provision the Framers put in to reduce the chances of mischief. The electors are supposed to vote for the candidates whose name they were elected under – in fact, 32 states (plus D.C.) have laws intended to bind the electors to their candidates. The Supreme Court this summer unanimously upheld such laws.

So-called “faithless electors” have on occasion broken their pledges, though never enough to actually swing the outcome. In 2016, for instance, five Democratic electors voted for people other than Hillary Clinton and two Republican electors voted for people other than Donald Trump.

In any event, the electors’ votes are supposed to be delivered to the vice president (in his capacity as president of the Senate) and a handful of other officials by Dec. 23 (the fourth Wednesday in December).

Wait – Congress has a role in this too?

Indeed it does. The newly elected 117th Congress will be sworn in on Jan. 3, 2021. Three days later, it is supposed to assemble in joint session to formally open the electors’ ballots, count them and declare a winner. Only then is the president officially “elected.”

Any pair of one senator and one representative can object to any of those votes as “not having been regularly given” (that is, not cast according to law). Following the 2004 election, for instance, Rep. Stephanie Tubbs Jones, D-Ohio, and Sen. Barbara Boxer, D-Calif., filed an objection against Ohio’s 20 electoral votes, alleging “numerous, serious election irregularities” in that state. But to sustain such an objection, both chambers must vote (separately) to do so. In the Ohio case, they both overwhelmingly rejected the challenge.

Each state is supposed to submit one set of electoral votes to Congress, and that’s what usually happens. Following the disputed Hayes-Tilden election of 1876, in which three states submitted two conflicting sets of returns, Congress passed the Electoral Count Act to try to set rules in case such a thing ever happened again. Under that law, if two conflicting sets are submitted – say, one by a Republican-run legislature and one by a Democratic governor – and the House and Senate cannot agree on which set is the legitimate one, then the electoral votes certified by the state’s governor are supposed to prevail. (Even stranger things are possible: In 1960, Hawaii’s governor first certified Vice President Richard Nixon’s electors, but after a recount certified Sen. John F. Kennedy’s electors. Both slates of electors met and voted for their pledged candidate; when the time came for Congress to decide which slate was the legitimate one, Nixon voluntarily deferred to Kennedy.)

Assuming that the usually ceremonial counting goes smoothly this year, Vice President Mike Pence will then announce whether he and President Trump have their jobs for another four years, or whether Joe Biden and Kamala Harris will take their places.

Note: This post was updated on Oct. 28 to reflect new information about deadlines in some states.