After the Democratic and Republican party conventions, the next big events on the U.S. political calendar are the debates. The Commission on Presidential Debates, which has sponsored the events since 1988, has scheduled three debates between President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden, on Sept. 29, Oct. 15 and Oct. 22, and one debate between Vice President Mike Pence and Sen. Kamala Harris on Oct. 7.

Although the debates have long been criticized on both substantive and stylistic grounds, they remain a major part of the way Americans elect their presidents. Here are five important things to know before the first debate kicks off next month in Cleveland.

To lay some groundwork for the upcoming presidential debates, we took a look back at the history of such debates. Data on voters’ perceptions of the debates’ helpfulness and their decision-making process was drawn from previous Pew Research Center surveys. Viewership was based mainly on figures made public by Nielsen Media Research, supplemented by estimates from the Commission on Presidential Debates and, in one case, The New York Times. Other sources included the commission’s records on prior debates and contemporaneous media reports from various publications.

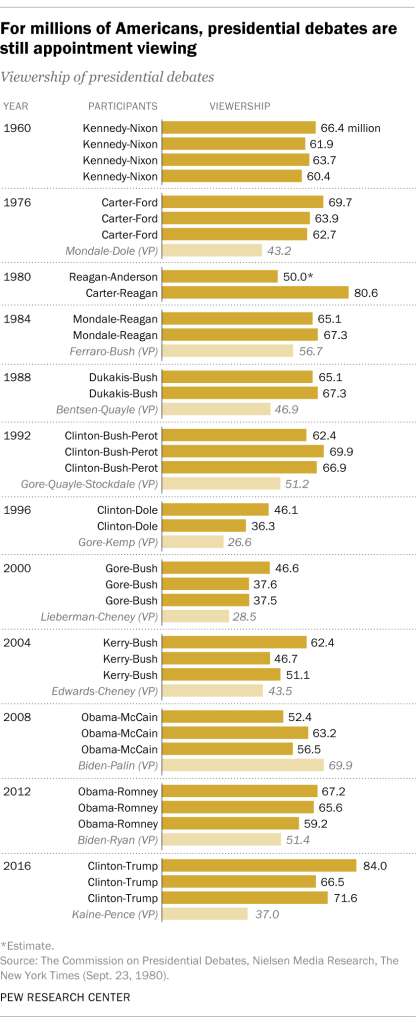

The debates draw a lot of viewers. Although viewership of the debates as a share of the total TV audience has broadly fallen over the decades, they can still attract more people than just about any other campaign event (or televised event of any kind that doesn’t rhyme with “Looper Hole”). In 2016, the first Clinton-Trump debate drew a record 84 million viewers, according to Nielsen Media Research, and 71.6 million tuned in to the third debate. By comparison, the final nights of the parties’ 2016 conventions attracted fewer than 35 million viewers each. (The Nielsen numbers included people watching at home on traditional TV channels; they didn’t count people who may have streamed the debates online or watched them at debate parties in bars and restaurants.)

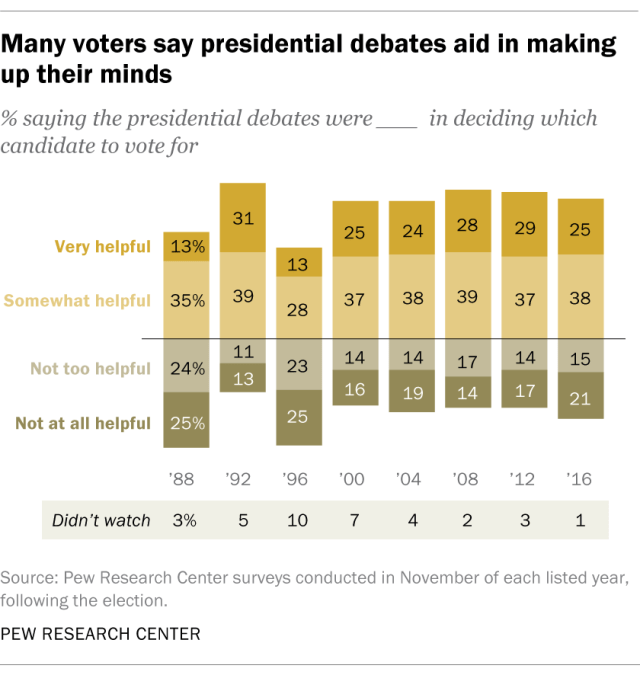

Voters find the debates useful, but not determinative. Post-election surveys conducted by Pew Research Center since 1988 have found that, in most cases, three-fifths or more of voters say the debates were very or somewhat helpful in deciding which candidate to vote for. The high point was 1992, when 70% of voters said the three three-way debates that year between Bill Clinton, George H.W. Bush and Ross Perot were at least somewhat helpful.

However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that large numbers of voters are waiting for the debates to make up their minds. In 2016, for example, only 10% of voters said they had definitively made up their minds “during or just after” the presidential debates. By comparison, 11% said they’d made up their minds in the days or weeks on or just before Election Day, 22% during or just after the party conventions, and 42% before the conventions.

The vice presidential debates are very much the undercard. In most years since 1976, when the candidates for vice president first had their own debate, the running mates have been runners-up when it comes to viewership. In 2016, for example, only 37 million people watched the vice presidential debate between then-Indiana Gov. Pence and Sen. Tim Kaine, 44% fewer than the viewership of the lowest-rated Clinton-Trump presidential debate (the second), which drew 66.5 million viewers. That was the biggest-ever drop-off between the vice presidential debate and the lowest-rated presidential debate.

The lone exception to this rule came in 2008, when more people (69.9 million) tuned in to the vice presidential debate between then-Sen. Biden and Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin than watched any of the three debates between Sens. Barack Obama and John McCain.

Today’s televised debates don’t much resemble the first ones. From the first debates between John Kennedy and Richard Nixon in 1960 through the 1988 edition, the candidates answered questions posed by a panel of journalists, with the moderator there mainly to explain and enforce the ground rules (sometimes more effectively than others) and keep the proceedings moving.

But by the 1980s, the panel format was in trouble. Critics said it too much resembled a joint press conference than an actual debate, and that the journalist-panelists took too much time and attention away from the actual candidates. The campaigns bickered constantly over who could or could not be a moderator or panelist. Finally, the League of Women Voters, which had organized the 1976, 1980 and 1984 debates, threw in the towel, leaving the job to the newly created debate commission.

In 1992, the commission tried a variety of approaches: Along with two of the traditional panel-style debates, it introduced a “town hall” event in which undecided voters asked the questions. That year’s vice presidential debate had a single moderator to pose questions. Based on feedback afterward, the commission decided to use only the single-moderator and town hall formats going forward. The lone exception was the town hall debate in 2016, which was co-moderated by Anderson Cooper of CNN and Martha Raddatz of ABC News.

The moderators are drawn mainly from the upper echelons of broadcast journalism. With one exception (James Hoge, editor in chief of the Chicago Sun-Times, who moderated the 1976 vice presidential debate), all of the moderators since 1960 have been prominent broadcast journalists. PBS has supplied the most moderators: 16 – and 12 of them in the person of the late Jim Lehrer, who moderated more debates than anyone else. The only other person to have moderated more than two presidential or vice presidential debates is Bob Schieffer of CBS News (2004, 2008 and 2012).