Among the collateral damage from the coronavirus pandemic has been the U.S. economy and the federal budget. The pandemic has caused massive economic disruption, and the government’s response has pushed the federal budget further out of balance than it’s been in nearly eight decades. But Americans appear to be slightly less concerned about the deficit than they have been in recent years.

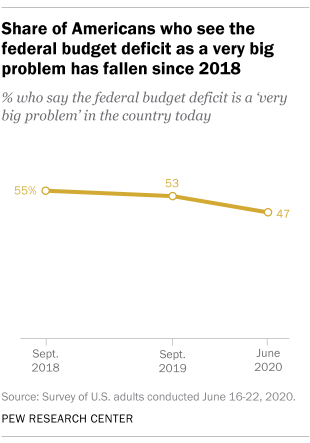

In a Pew Research Center survey conducted June 16-22, just under half of U.S. adults (47%) called the deficit “a very big problem” in the country today – down from 55% in the fall of 2018. Over roughly that same period, the deficit grew from $779.1 billion at the end of fiscal 2018 to $2.8 trillion as of the end of July, according to data reported Wednesday by the Treasury Department. (The federal fiscal year ends on Sept. 30.)

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a dramatically higher federal budget deficit, with relief spending soaring and tax revenues tumbling. We thought it would be interesting to combine Americans’ views on the deficit with a deeper look at how it has changed in recent years.

For the attitudinal data, we surveyed 4,708 U.S. adults from June 16 to 22, 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. (Here are the questions asked for this report, along with responses, and its methodology. You can also read more about the ATP’s methodology.) Budgetary data came from several sources. For the current fiscal year’s receipts and outlays, we used data from the Treasury Department’s Office of the Fiscal Service. Historical budget figures were taken from the Office of Management and Budget. We also used the latest estimates of gross domestic product from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Additional background and analysis were obtained from various Congressional Budget Office reports.

The deficit landed roughly in the middle of the pack among the 10 issues asked about in the June survey. The share of adults calling it a very big problem was higher than the share saying the same about climate change (40%) or illegal immigration (28%), but lower than the shares who called ethics in government and the pandemic very big problems (63% and 58%, respectively).

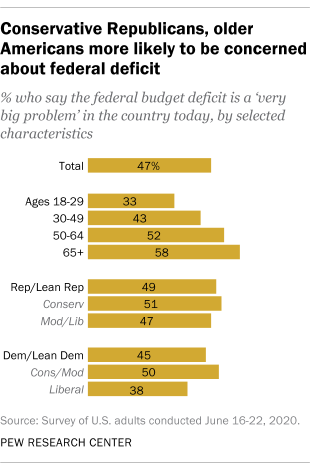

Older people and Republicans are more likely to call the deficit a very big problem, while Democrats – especially liberal Democrats – are less likely to do so. There are few or no differences between responses by men and women or among people of different education or income levels.

Concern about the deficit tends to rise with age. Among Americans 65 and older, 58% said the deficit is a very big problem, compared with 52% of 50- to 64-year-olds, 43% of 30- to 49-year-olds and 33% of 18- to 29-year-olds.

Republicans and Republican-leaning independents were somewhat more likely to call the deficit a very big problem: 49% did so, compared with 45% of Democrats and Democratic leaners. Viewed through ideology, self-described liberal Democrats were considerably less likely to call the deficit a very big problem (38%) than conservative Republicans (51%), conservative and moderate Democrats (50%) or moderate and liberal Republicans (47%).

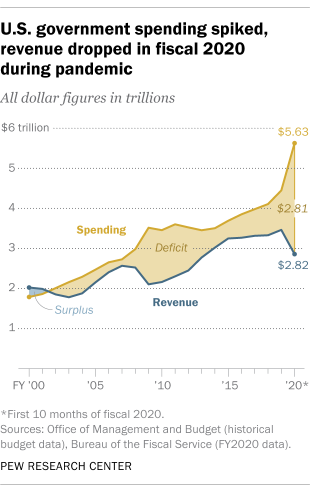

The federal government has run deficits nearly every year since the Great Depression and consistently since fiscal 2002. Through the first 10 months of fiscal 2020, the government took in $2.82 trillion in revenue and spent $5.63 trillion, for a year-to-date deficit of just over $2.8 trillion, according to the Treasury Department’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service. Through the first 10 months of fiscal 2019, by comparison, the deficit stood at $866.8 billion.

The deficit began widening dramatically in April, as the government started spending hundreds of billions of dollars on coronavirus relief and response. In the April to July 2020 period, federal revenues were about 9.8% below the same period in 2019, while spending more than doubled, according to Treasury Department data.

Absent a major fiscal turnabout in the next two months, the federal budget deficit – which is funded by borrowing – is poised to push up against a raft of past records. The deficit accounts for about half of total federal spending (49.9%) so far this fiscal year; the last time borrowing made up that much of federal spending (1942 to 1945), the United States was in the middle of fighting World War II. (Measuring the deficit as a percentage of total spending shows the extent to which the federal government is relying on borrowed money, rather than tax receipts, to fund its expenditures.)

Looking at the deficit as a percentage of gross domestic product rather than in raw dollars puts it in the context of the total U.S. economy and makes comparisons over time more meaningful. As of the end of the fiscal third quarter in June, the deficit represented 13.1% of GDP, also a level not seen since World War II. By comparison, during the Great Recession in fiscal 2009, the deficit accounted for 40.2% of total spending and reached 9.8% of GDP.

As the Great Recession eased, the deficit declined relative to both total spending and GDP from 2009 to 2015, but it has been rising on both measures ever since. In April, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the current fiscal year’s deficit will come in at roughly $3.7 trillion, or 17.9% of GDP – the largest shortfall since 1945. The CBO also projected that in fiscal 2021, the deficit would be $2.1 trillion.

Annual budget deficits add to the national debt, which as of July 31 stood at more than $26.5 trillion. Economists, budget analysts, politicians and others have argued for decades about how much debt is too much and what effects persistent deficits and heavy debt loads could have on the federal government and the wider economy.

One issue is that the more the government pays out in interest on its debt, the less money it has available for other programs and priorities. In fiscal 2019, the federal government paid out $375.2 billion in net interest on its debt, amounting to 8.4% of total expenditures. As a share of overall spending, interest payments have been rising since 2015 but are still well below levels seen in earlier decades: In fiscal 1996, for example, interest payments accounted for 15.4% of total federal spending. (The dollar amount of interest the federal government pays is a factor not just of how much it borrows, but what interest rates it’s charged.)

Other observers have warned that if the national debt grows large enough, it could absorb so much of investors’ money that other borrowers, particularly in the private sector, would have trouble raising cash at affordable rates. So far, though, that doesn’t appear to be happening: Interest rates around the world remain quite low even as governments borrow heavily to fight the pandemic.

The CBO cites other possible consequences if the national debt continues to grow as a percentage of GDP. They include depressed economic output; more interest payments flowing out of the U.S. to foreign debtholders; and increased risk of a fiscal crisis, in which investors lose confidence in the federal government’s financial health and abruptly raise the interest rates they demand to fund the debt.

Some economists, however, take a different view. Under the general term “Modern Monetary Theory,” or MMT, they argue that the U.S. government can and should fund its spending by creating money directly, rather than borrowing it. The constraint on spending, MMT adherents say, should be on maintaining a sustainable inflation rate, not a balanced budget or particular debt-to-GDP ratio. But while MMT has gained some purchase on the leftward side of politics, it remains controversial.